Researchers found distinct blood flow patterns in LVAD patients who had strokes vs. those who didn't.

Early stroke after left ventricular assist device implantation: role of right heart failure

Go to source). These implantable devices enhance blood circulation and are often the final treatment option when other therapies no longer work. With over 14,000 recipients and heart failure affecting 26 million people worldwide, LVAD use is expected to rise.

TOP INSIGHT

Did You Know?

People with #LVADs (Left Ventricular Assist Device) face an 11% to 47% higher risk of developing #bloodclots that can travel to the brain and cause a #stroke. #medindia #heartfailuretreatment #strokeriskreduction

The Complex Relation Between LVAD and Stroke

It’s not clear why some The researchers created “digital twins” of real patients with LVADs to map their blood flow. Their findings revealed new insights into how strokes might emerge.

“We are in an age where there is quite a bit of data that we have access to, and we know a lot about how fluid moves through the arteries and veins,” said Debanjan Mukherjee, senior author of the study and assistant professor in the Paul M. Rady Department of Mechanical Engineering at CU Boulder. “We are looking at blood flow patterns as information that currently is not incorporated in clinical practice.”

Engineering concepts like fluid dynamics can offer a unique lens for looking at complex medical issues and provide information that other diagnostic tools might miss, the authors said. “Knowledge gained from this study can help us develop patient-specific implant techniques to reduce the likelihood of stroke in patients with durable LVADs,” said Jay Pal, professor and chief of cardiac surgery at the University of Washington, and a co-author of the study.

Stroke risk with LVADs in Heart Failure

The body relies on a constant supply of fresh blood and oxygen to function. Heart failure occurs when the heart can no longer pump the amount of blood the rest of the body needs. During a healthy heartbeat, the left ventricle of the heart constricts and pushes blood into the arteries, where it travels to the body’s organs, muscles and bones.

But in people with heart failure, the left ventricle can become weak and ineffective. An LVAD attaches directly to the heart, bypasses the left ventricle and pumps blood straight into the aorta, the biggest artery in the body.

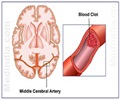

These clots can travel through the body and land in a variety of places, but the arteries supplying blood to the brain are an especially dangerous spot. Clots that get stuck there can restrict or cut off blood flow to parts of the brain and cause a stroke.

In the current study, supported by the National Institutes of Health and CU’s AB Nexus initiative, Mukherjee and his colleagues explored whether different blood flow patterns in people with LVADs could explain who does and doesn’t get strokes.

To answer this question, the research team, led by former graduate student Akshita Sahni of CU Boulder, collected data from 12 people with LVADs. Six had developed strokes after their LVAD implantation, and six had not.

The group created 3D digital twins of each LVAD patient using detailed imaging of the aorta, nearby blood vessels and the part of the LVAD that attaches to it. The researchers also integrated individual’s clinical information, such as blood pressure and heart rate, into the models.

“We are basically digitally recreating something that's going on inside the body,” Mukherjee said.

Using the twins, the group was able to estimate the patterns of blood flow through each person’s aorta. They also simulated how blood might flow through the same people before they got their LVADs.

The team also found the LVADs changed the blood flow patterns in each patient, creating a “jet” that pushed blood into the aorta at a different angle than normal blood flow from the heart.

Such differences in blood flow could help shed light on LVAD patients’ risk level for

The findings could help improve treatments and outcomes for people with heart failure. With this information, health care providers can personalize how they surgically implant and monitor LVADs in their patients. They might also be able to anticipate their patients’ level of risk and provide more customized treatments for each person.

Mukherjee and his collaborators are planning additional research on the topic, but he emphasized that some of this work will only be possible with federal support and funding.

“In these times, it is important to remember how much federal agency support means to getting studies like these completed and developed further,” he said.

Reference:

- Early stroke after left ventricular assist device implantation: role of right heart failure - (https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10797350/)

Source-Eurekalert

MEDINDIA

MEDINDIA

Email

Email