What is a Whipple’s Procedure?

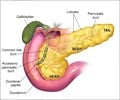

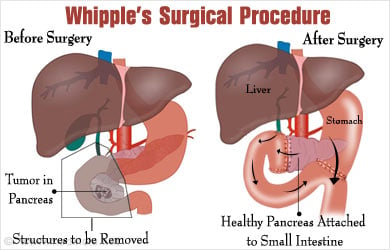

A pancreatico-duodenectomy, commonly referred to as a Whipple’s procedure, is a complex surgery in which the main portion of the pancreas (the “head”) is removed along with the entire duodenum (first portion of the small bowel) and gallbladder, and the drainage of the stomach, bile duct and pancreas are surgically reconnected.

"Surgeons must be very careful when they take the knife! Underneath their fine incisions stirs the culprit - Life!" - Emily Dickinson

The Whipple’s procedure was actually first described by the Italian surgeon Alessandro Codivilla in 1889 and first performed by the German surgeon Walther Kausch in 1909. The American surgeon Allen Whipple’s is epynomous with pancreaticoduodenectomy because of his many improvements and refinements to the procedure in 1935. It is most commonly performed for pancreatic cancer but is also less commonly indicated for duodenal tumors, periampulary (the duct draining pancreatic and biliary secretions into the duodenum) abnormalities or, increasingly, for chronic pancreatitis.

Patients with a diagnosed pancreatic cancer must be carefully selected for undergoing the Whipple’s procedure to ensure maximum success and minimal complications. The tumor should be:

- Confined to the head of the pancreas,

- Not invading the major blood vessels coursing behind the pancreas (the superior mesenteric artery and vein),

- There should be no evidence of metastatic disease

- and the patient must be medically fit enough to undergo a major abdominal surgery.

If any of these criteria are not met, i.e., the tumor is locally or distantly invasive or the patient is too ill to tolerate surgery, then surgery is not performed because the risks of, death, complications or incomplete tumor removal outweigh the benefits of surgery.

In the above situation, patients are treated with chemotherapy and/or radiation only for their disease.

In the case of duodenal tumors, the same basic criteria exist to determine surgical candidacy. For benign periampulary obstructions or chronic pancreatitis, patients must be carefully selected and surgery should be avoided if possible, especially in the case of pancreatitis where the potential success of the procedure is uncertain.

How is the Whipple’s Procedure Performed?

After a thorough preoperative work up, the patient is taken to the operating room and placed under general anesthesia. The operation takes anywhere between 3-6 hours on average, depending on the patient’s severity of disease. A large abdominal incision (either midline or subcostal) is performed and the abdominal contents are examined thoroughly for evidence of metastatic disease or local invasion into adjacent structures (especially the superior mesenteric artery and vein behind the pancreas). If the patient is deemed resectable intraoperatively, then the surgeon proceeds to remove the entire duodenum and the head of the pancreas (leaving behind the body and tail, or about 50% of the entire pancreatic mass). The reason why both duodenum and pancreatic head have to be removed is because they share a common blood supply, so in the case of pancreatic cancer, even if there is no disease in the duodenum, it must be removed because it becomes completely devascularized when the head of the pancreas is removed. Conversely, a duodenal tumor close to the pancreas requires removal of a normal pancreatic head.

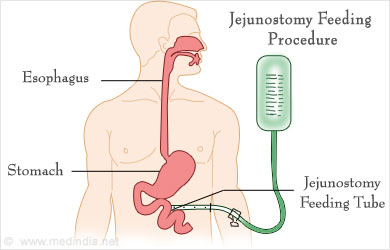

After removing the tumor, pancreatic head, duodenum, gallbladder and—sometimes—a part of the stomach - several connections must be reestablished to restore continuity of the digestive tract including stomach drainage into the small bowel, bile duct drainage from the liver and pancreatic duct drainage from the remaining pancreatic tissue. These connections are made with great care so as to avoid leaks or strictures. A feeding jejunostomy tube is surgically placed at the end of the procedure to ensure a rapid return to nutritional intake. Surgical drains are also placed near the connections of the stomach, small bowel, bile duct and pancreatic duct.

Postoperatively, patients are usually kept in the ICU for close observation until they are deemed stable and then sent to the regular ward. An average stay is 7-14 days after the operation and patients are eating normally and ambulating prior to discharge. The surgical drains are removed 5-14 days after the surgery and the feeding jejunostomy is removed after one month, depending on the patient’s own ability to take food orally.

What are the Risks Associated with Whipple’s Procedure?

Aside from the ubiquitous complications associated with any surgery (death, bleeding, infection), surgical complications specific to the Whipple’s procedure include:

- Pancreatic fistula

- Delayed gastric emptying

- Biliary leak or obstruction

- Bowel leak

- Intra abdominal bleeding

- Intra abdominal sepsis or abscess

- Incomplete tumor removal.

Medical complications include heart attack, stroke, pulmonary emobolus, renal or hepatic insufficiency, pneumonia and urinary tract infection. The mortality risk is below <5%. The overall complication rate ranges from 30-60%.

The most dreaded complication of the Whipple’s procedure is a pancreatic fistula, or continuous leak of pancreatic secretions where the pancreas was reconnected to the intestines. Often such fistulae are clinically insignificant and resolve spontaneously without problems, but because of the corrosive nature of pancreatic digestive enzymes, a fistula may lead to abscess formation, sepsis and catastrophic bleeding if nearby major blood vessels are eroded by contiunous exposure to pancreatic enzymes. Pancreatic fistula is the major cause of postoperative mortality associated with the Whipple’s procedure, but the overall mortality rate of this complication is <5% in most experienced centers.

There is controversy in the medical literature as to whether administration of octreotide, a drug that dramatically reduces pancreatic secretions, is beneficial in preventing pancreatic fistulae.

Delayed gastric emptying refers to the stomach’s inability to properly channel ingested food into the small intestines. A modification of the Whipple’s procedure in which the entire stomach is preserved (Pylorous Preserving Pancreaticoduodenectomy, or PPPD) has greatly reduced the incidence of this complication.

Intrabdominal abscess and sepsis following a Whipple’s procedure occurs in 1-12% of cases. It is imperative to make the diagnosis with a CT scan, approcpriately drain the infected collection and to treat with intravenous antibiotics.

Hemorrhage following a Whipple’s procedure occurs in 3-13% of cases and may be managed nonoperatively, but uncontrolled bleeding usually requires a second operation. Late hemorrhage (several weeks after the operation) is associated with a high mortality rate (15-58%) because the underlying cause often involves erosion of major blood vessels from a pancreatic fistula.

Recovery after the Whipple’s Procedure

Patients usually stay in the hospital 1-2 weeks following an uncomplicated Whipple’s procedure. In the case of pancreatic or duodenal cancer, postoperative (“adjuvant”) chemotherapy is often employed, with or without radiation, beginning 1-2 months after the surgery. If complications arise, the time to starting chemotherapy can be significantly delayed. The most common chemotherapeutic agents used for pancreatic cancer are gemcitabine, 5-fluorouracil, cisplatin and paclitaxel.

Complete recovery from surgery is often achieved within 1-3 months of the procedure. Patients with chronic pancreatitis who have undergone a Whipple’s procedure are cured of their chronic pain in 58-75% of cases.

Prognosis of Pancreatic Cancer

The overall survival in patients with pancreatic cancer is very poor with 5 year survival rates of 14% for Stage I disease and 1% for Stage IV disease. Complete surgical resection is the only chance for curing pancreatic cancer but this is only possible in a minority of patients with early stage disease.

MEDINDIA

MEDINDIA

Email

Email