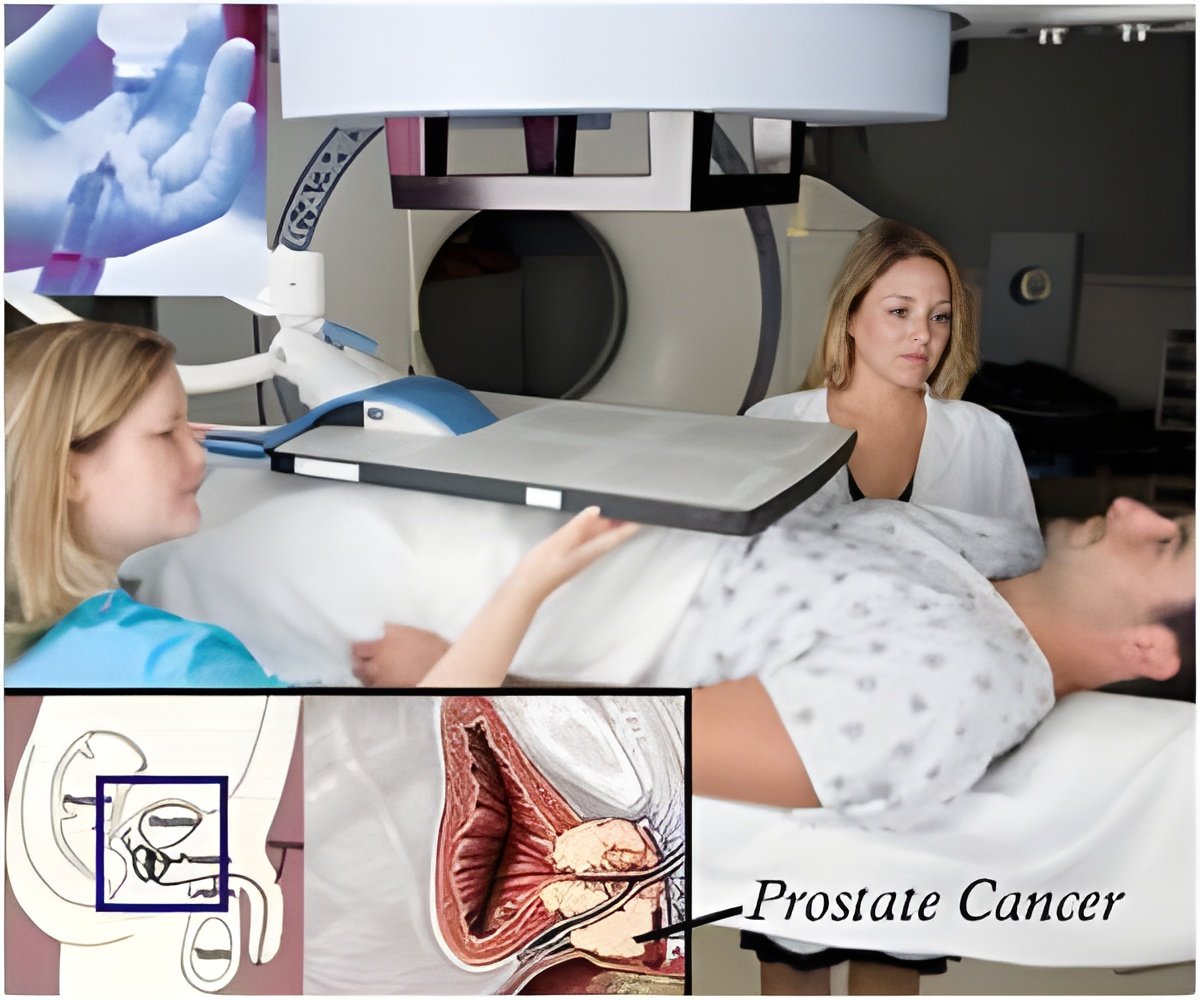

Despite the fact that no medical organization recommends prostate cancer screening for men older than 75, many primary care doctors continue to administer the prostate-specific antigen test to even their oldest patients.

In a research letter published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, UTMB researchers found a high variability in standard PSA-ordering practice among primary care physicians. Some doctors ordered the test for their older male patients regularly, despite more than a decade of recommendations against doing so. The doctors' tendency to order the test had little to do with measurable patient characteristics.

"Our results suggest that a major reason for the continued high PSA rate is decision-making by the physicians," said senior author Dr. James Goodwin, director of UTMB's Sealy Center on Aging. "That's why there was so much variation among physicians, after accounting for differences among patients. It is clear that some of the overuse is because of preferences of individual patients, but the conclusion of our results is that much more is coming from their primary care physicians."

The purpose of UTMB study was to determine the role primary care physicians play in whether a man receives PSA screening. The study looked at the complete Medicare Part A and Part B data for 1,963 Texas physicians who had at least 20 men age 75 or older in their panels and who saw a man three or more times in 2009. Of the 61,351 patient records examined, 41 percent of men received a PSA screening that year, and 29 percent received a screening ordered by their primary care physician.

Which primary care physician a man sees explained approximately seven times more of the variance in PSA screening than did the measurable patient characteristics, such as age, ethnicity, and location, according to the study.

"Overtesting can create harms, including overdiagnosis," said Dr. Elizabeth Jaramillo, lead author and an instructor of internal medicine-geriatrics at UTMB. "The vast majority of prostate cancers are so slow growing that an elderly man is much more likely to die of another condition in his lifetime than from the cancer."

Advertisement

Source-Eurekalert

![Prostate Specific Antigen [PSA] & Prostate Cancer Diagnosis Prostate Specific Antigen [PSA] & Prostate Cancer Diagnosis](https://images.medindia.net/patientinfo/120_100/prostate-specific-antigen.jpg)