- A mathematical model proves the older theory that knuckle-cracking is due to the popping of bubbles or gas pockets present in the synovial fluid in joints

- A complete collapse of the bubbles is not needed to produce the cracking sound; hence bubbles can persist even after the generation of the sound

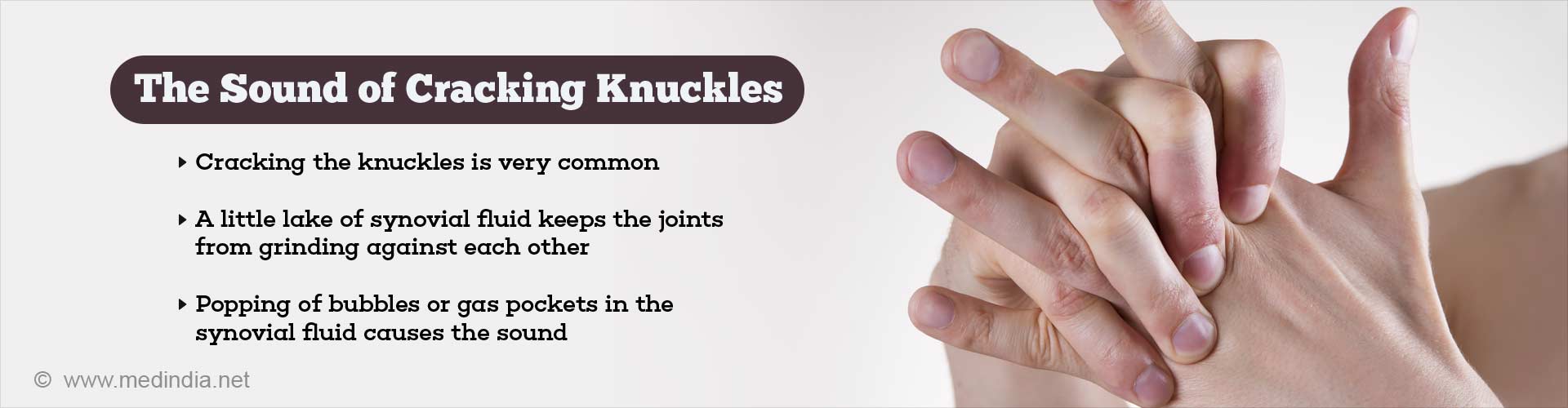

Cracking the knuckles is very common - some proven facts about them are that not all joints can be cracked and among those that can be cracked there has to be a gap of 20 minutes to crack them again.

But how can we explain the source of the sound?

So far, the joints most studied for explaining the source of the sound has been the metacarpophalangeal joints. Metacarpophalangeal joints are the joints between the metacarpal bones (those in between the finger bones and the wrist bones) and the phalanges of the fingers.At the metacarpophalangeal joints, there is a little lake of synovial fluid that keeps the joints from grinding on each other. Gas, mostly carbon dioxide dissolves and stays in the synovial fluid. When we crack our knuckles, the bones are pulled away from each other. This causes a sudden drop in the pressure in the middle of the joint. The dip in pressure allows the gases to come together, forming bubbles.

Cavitation is the formation of bubbles in the synovial fluid as a consequence of forces acting on the liquid.

In 1971, Unsworth and co-workers through extensive experiments concluded that cavitation and the subsequent collapse or popping of cavitation bubbles in the synovial fluid was the source of the cracking sound. This theory was widely accepted for over 40 years.

In 2015, Greg Kawchuk of the University of Alberta and co-workers challenged the cavitation theory. They used an MRI scanner to record what was happening inside the fingers of a frequent knuckle-cracking volunteer.

- The images showed a sudden appearance of a bulge in the knuckle as it is cracked. This prompted Kawchuk and his colleagues to hypothesize that the formation of the bubble, when the joint is pulled apart, might be responsible for the cracking noise.

- The images also showed that the bubbles persisted long after the cracking sounds were observed and provided evidence that gas bubbles existed in the synovial fluid long after the cracking sounds were observed.

Current Study

Abdul Barakat, a professor of biomechanics and a master’s student in his lab, Vineeth Suja at the Ecole Polytechnique in France grew interested in knuckle-cracking on reading the 2015 paper.They aimed to support the available experimental data and to test the older theory, whether bubbles collapsing could produce a sound of that magnitude.

They developed a mathematical model of the hand’s metacarpophalangeal joint with a bubble in it and experimented with a lot of factors that could lead to the generation of the sound, like the thickness of the surrounding fluid, or the speed at which the joints.

The idea was very simple - they compared the theoretical sounds of the bubble collapsing in the model with recordings of Suja and others cracking their knuckles.

"We wanted to look at it mathematically because all the previous work was based on observation or imaging, so we tried to build a mathematical model that described the physical phenomena that governed this," Barakat said.

Results of the study

- The sounds predicted by the model matched the volume and frequency of the recordings fairly well, even if the bubble disappeared suddenly, rather than slowly.

- The model also showed that a partial collapse (30 to 40 percent) of the bubble is enough to replicate the recorded sound, thus agreeing with Kawchuk’s images of a bulge in the knuckle long after the sound had passed.

- Another finding was that an important factor that seemed to make a difference to the type of sound generated was how much force is applied to the knuckle.

Limitations of the study

The researchers did not study what happens as the bubble forms — the model merely assumes its existence.Future steps

The plausible next step would be to see whether the sound is created during the formation of the bubble in a similar model as well. This model would study how both bubble formation and bubble collapse might contribute to the sound.Knuckle-cracking is neither beneficial or harmful and does not cause arthritis, contrary to popular belief. Understanding knuckle-cracking can provide some insight to physiologists about how healthy joints move.

Reference:

- V. Chandran Suja et al. “A Mathematical Model for the Sounds Produced by Knuckle Cracking”, Scientific Reports (2018). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-018-22664-4.