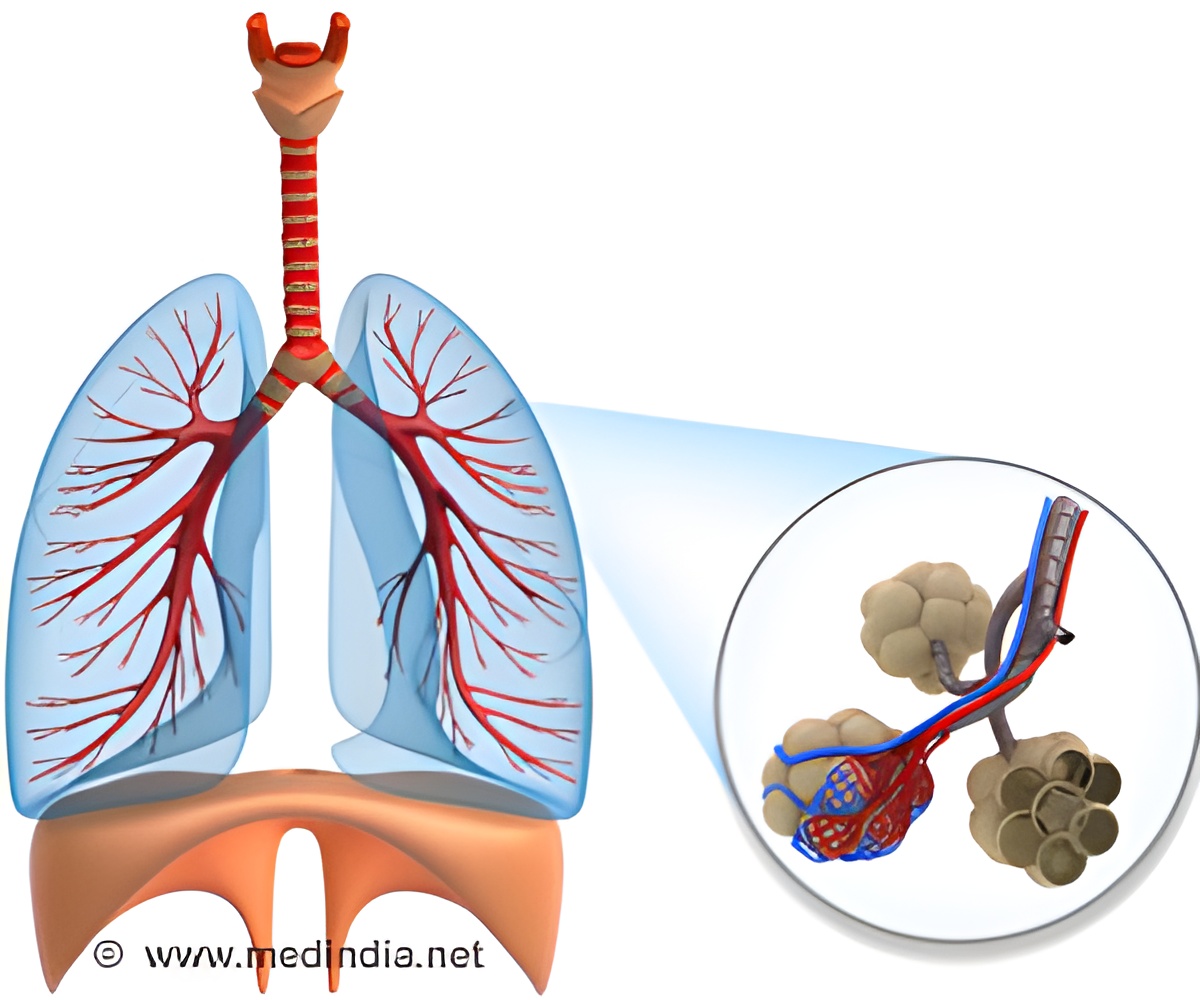

The microbial communities are linked to each other across the body, and are linked to susceptibility to respiratory infections in babies, stated new research.

TOP INSIGHT

The networks from children who developed more respiratory tract infections showed small, less-well connected clusters from early on in life, and they tended to change more over time, even before infections occurred.

The researchers, led by Professor Debby Bogaert, collected samples one week after birth and then at two, four and six months from the nose, mouth and gut of 120 healthy babies who were enrolled in the large prospective Microbiome Utrecht Infant Study in The Netherlands. The researchers also gathered information on lifestyles and environmental factors affecting the babies, and how many respiratory infections they developed in the first year of life.

Dr Clerc said: "We analysed the bacteria present in the nose, mouth and gut at multiple timepoints and used a mathematical algorithm to create networks that describe how all of those microbes are linked at each timepoint and over time."

The researchers found that one week after birth the microbial networks were already well-defined in babies who went on to experience 0-2 infections in the first year of life. These networks were composed of four large clusters of bacteria: three clusters were specific to either the nose, the mouth or the gut, and a fourth cluster of bacteria, composed of species of mixed origin, linked the other three groups. The size, composition and connectivity of these clusters remained stable during the year.

"Our findings may lead to new insights into ways of using these cross-site microbial connections to prevent respiratory infections in childhood and to understand how susceptibility to disease is linked to the way these microbial communities mature. Further, interventions immediately before or after birth, such as caesarean section or antibiotic treatment, might have more impact than we previously predicted because of their extended effect on the ways microbial communities across the body are connected."

The babies were recruited before birth at the Spaarne Hospital in The Netherlands during routine prenatal appointments with midwives and obstetricians. Only healthy children were included, and those that were born early or with congenital abnormalities or complications around the time of birth were excluded from the study.

"Although the methods described in this study may offer a new way of identifying babies who are at greater risk of infection, we need more research to confirm the link between microbial networks and respiratory effects and the potential for increased susceptibility to respiratory infection."

Source-Eurekalert

MEDINDIA

MEDINDIA

Email

Email