B cells of the immune system produce antibodies or 'smart bullets' which specifically target invaders such as pathogens and viruses leaving the harmless molecules alone.

"It is critical for B cells to respond either fully or not at all. Anything in between causes disease," said the study's senior author, Alexander Hoffmann, a professor of microbiology, immunology and molecular genetics in the UCLA College of Letters and Science. "If B cells respond wimpily when there is a real pathogen, you have immune deficiency, and if they respond inappropriately to something that is not a true pathogen, then you have autoimmune disease."

The antibodies produced by B cells attack antigens — molecules associated with pathogens, microbes and viruses. A sensor on the cell's surface is meant to recognize a specific antigen, and when the sensor encounters that antigen, it sends a signal that enables the body's army of B cells to respond rapidly. However, there may be similar molecules nearby that are harmless. The B cells should ignore their signals — something they fail to do in autoimmune diseases.

So how do the B cells decide whether to start producing antibodies?

"These immune cells are somewhat hard of hearing, which is appropriate because the powerful and potentially destructive immune responses should jump into action only when danger calls, not when it whispers," said Hoffmann.

The B cells make their response only when a rather high threshold is reached, Hoffmann and his colleagues report. A small or moderate signal — from a harmless molecule, for instance — gets no response, which reduces the risk of false alarms.

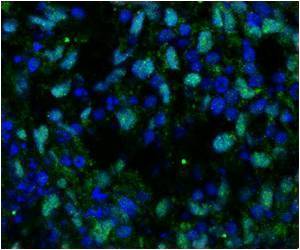

We have billions of B cells, and each one creates this threshold through a molecular circuit involving two molecules. One of these molecules, known as CARMA1, activates the other, IKKb, which further activates the first one.

He and his colleagues developed mathematical equations based on the molecular circuit and were then able to simulate, virtually, B cell responses. The team's resulting predictions were tested experimentally by their collaborators at the Laboratory for Integrated Cellular Systems at Japan's RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Sciences. In one part of the study, the researchers made specific mutations in IKKb so that it could not signal back to CARMA1. They also made mutations in CARMA1 to prevent it from receiving the signal from IKKb. In both cases, the B cells responded partially, some of the time, like a weakly inflating airbag.

"It became a gray-zone response rather than a black-and-white response," said Hoffmann, who constructs mathematical models of biology.

The research could lead to better diagnosis of disease if patients with an autoimmune disorder, such as lupus, have a defect in this molecular circuit.

Source-Eurekalert

MEDINDIA

MEDINDIA

Email

Email