Experts are speculating that the victim could have been infected by an entirely new variation of the virus from an animal.

Buckets of bleach, a ubiquitous symbol of Ebola's virulence as the epidemic cut a murderous swathe though the country last year, began to reappear outside shops and homes as the capital came to terms with the news that the virus was back.

As the epidemic began to subside at the end of last year the handshakes made a comeback, but the "Ebola shake" was back as Monrovians met in the streets.

Health minister Bernice Dahn asked citizens to prepare themselves for further cases, although no new infections had emerged.

The country's neighbors Guinea and Sierra Leone are both still battling the outbreak, which has killed more than 11,200 people across west Africa, but the coastal Margibi County where the teenager died is nowhere near either border.

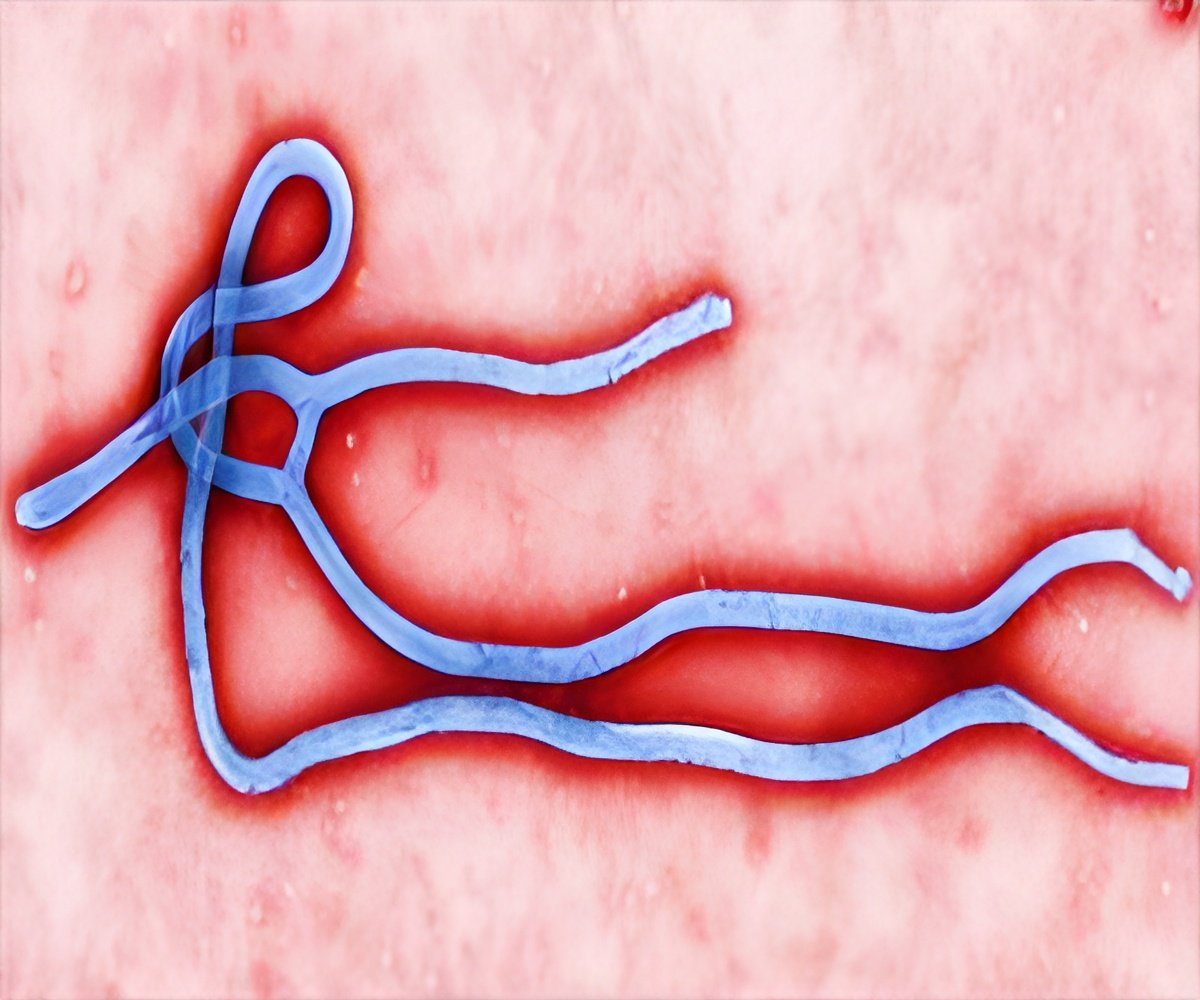

Ebola is spread among humans via the bodily fluids of recently deceased victims and people showing symptoms of the tropical fever, which include vomiting, diarrhea and -- in the worst cases -- massive internal hemorrhaging and external bleeding.

During the months of peak transmission from August to November last year Liberia was the setting for some of the most shocking scenes from the outbreak, by far the worst in history.

Schools remained shut after the summer holidays, unemployment soared as the formal and black-market economies collapsed and clinics closed as staff died and non-emergency healthcare ground to a halt.

Parents found themselves mulling the grim prospect of further disrupting their children's education or sending them to school as usual -- and possibly exposing them to danger, should Ebola re-enter the capital.

Patricia Sleboh, a mother-of-three, told AFP she would rather keep her children from classes than risk "losing them to Ebola".

"I am waiting to see if the health authorities will give us good reason not to worry. If not, I am stopping my kids from going to school," she told AFP.

Source-AFP

MEDINDIA

MEDINDIA

Email

Email