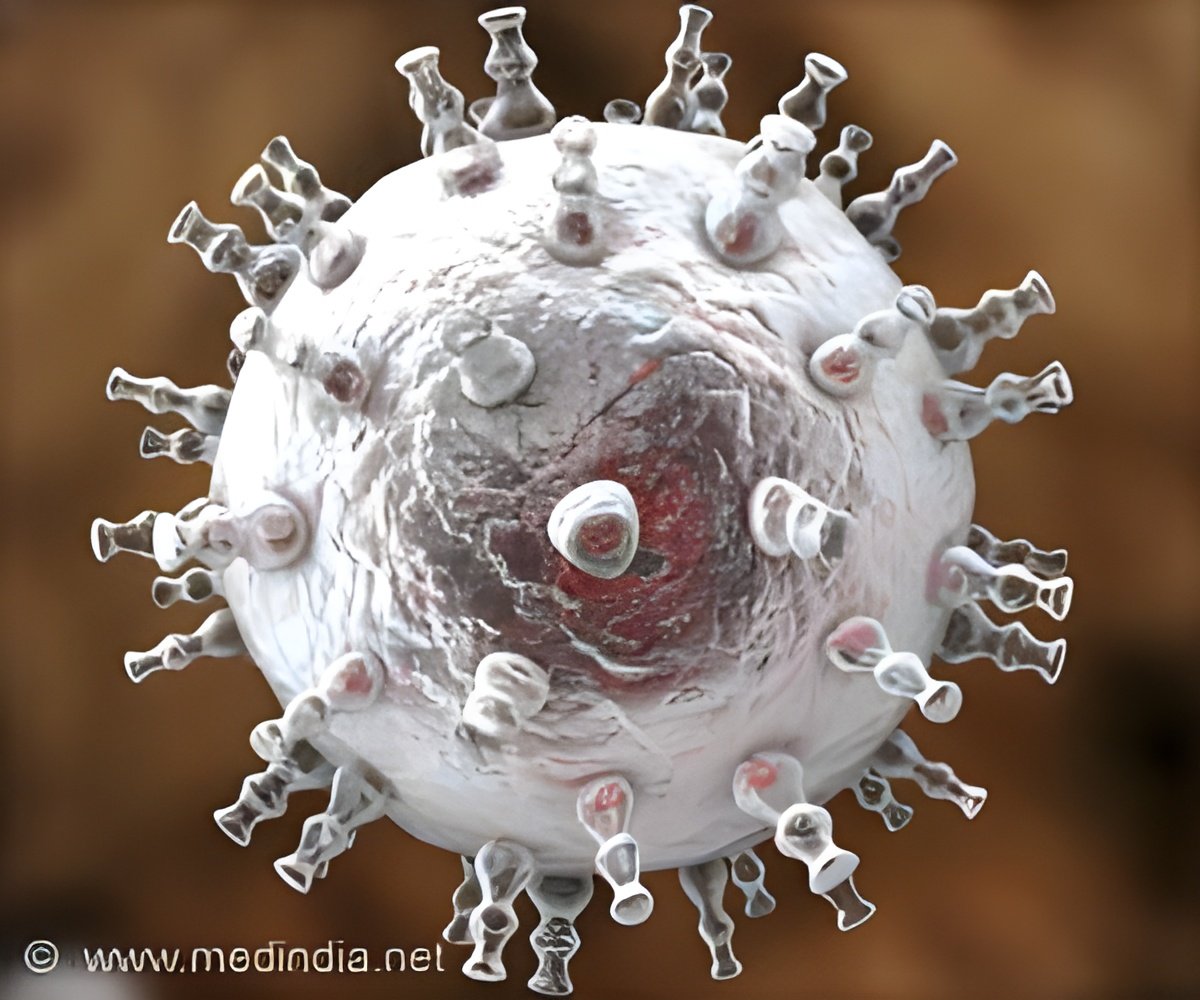

Novel way to attack herpesviruses has been identified. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a major cause of birth defects and transplant failures. Scientists have uncovered the mechanism that allows the virus to replicate.

TOP INSIGHT

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a major cause of birth defects and transplant failures. Scientists have uncovered the mechanism that allows the virus to replicate which can lead to a new therapeutic target to attack cytomegalovirus and other herpesviruses.

Normally, when a virus enters your cell, that cell blocks the virus's DNA and prevents it from performing any actions. The virus must overcome this barrier to effectively multiply.

To get around this obstacle, cytomegalovirus doesn't simply inject its own DNA into a human cell. Instead, it carries its viral DNA into the cell along with proteins called PP71. After entering the cell, it releases these PP71 proteins, which enables the viral DNA to replicate and the infection to spread.

"The way the virus operates is pretty cool, but it also presents a problem we couldn't solve," said Noam Vardi, Ph.D., postdoctoral scholar in Weinberger's laboratory and first author of the new study.

"The PP71 proteins are needed for the virus to replicate. But they actually die after a few hours, while it takes days to create a new virus. So how can the virus successfully multiply even after these proteins are gone?"

To confirm their findings, the team created a synthetic version of the virus that allowed them to adjust the levels of the IE1 proteins using small molecules. With this technique, they could let the virus infect the cell while controlling how quickly the IE1 protein would break down in the cell.

This study could have broad implications for the scientific community, which has been struggling to determine how cells maintain their identity over time. During development, for instance, stem cells choose a path based on the proteins that surround them. But even after these initial proteins disappear, the specialized cells don't change. So, stem cells that turn into neurons during development continue to be neurons long after those proteins are gone.

"The issue is similar for the virus," explained Weinberger, who is also a professor of pharmaceutical chemistry at UC San Francisco. "It was not clear what mechanisms allowed the virus to continue replicating long after the initial signal from the PP71 had decayed to a whisper.

Our findings uncover a circuit encoded by the virus that controls its fate and indicates that such circuits may be quite common in viruses."

The new study could lead to a new therapeutic target to attack cytomegalovirus and other herpesviruses, such as Epstein-Barr virus that causes mononucleosis and herpes simplex virus 1 and 2 that produce most cold sores and genital herpes.

Source-Eurekalert

MEDINDIA

MEDINDIA

Email

Email