‘With lab developed mini-brains that have the potential to develop blood vessels, researchers can study a range of injury conditions, drugs that are being tested and conditions - such as stroke and diabetes - together.’

Tweet it Now

The networks of capillaries within the little balls of nervous

system cells could enable new kinds of large-scale lab investigations

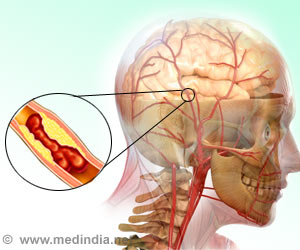

into diseases, such as stroke or concussion, where the interaction

between the brain and its circulatory system is paramount, said Diane

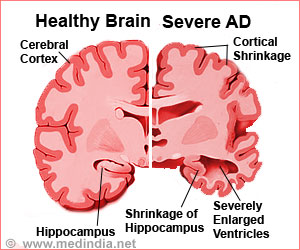

Hoffman-Kim, senior author of the study in The Journal of Neuroscience Methods. More fundamentally, vasculature makes mini-brains more realistic models of natural noggins."This is exciting because real brains have vasculature," said Hoffman-Kim, an associate professor of medical science and of engineering at Brown. "We rely on it. For our neurons to do their thing, they have to be close to some blood vessels. If we are going to study lab models of the brain, we would love for them to have vasculature, too."

Making the most of mini-brains

Especially because scientists can make them by the hundreds, mini-brains hold promise not only for advancing medical and scientific research, but also for doing so with less need for animal models. Hoffman-Kim's lab first described its mini-brain method in 2015. While the engineered tissues appeared relatively simple compared to some others, they were also relatively easy and inexpensive to make.

But what had remained unnoticed at the time, even by the inventors, was that the little 8,000-cell spheres cultured from mouse cells were capable of growing an elementary circulatory system.

Advertisement

The new study features a wide variety of imaging experiments in which staining and fluorescence techniques reveal those different cell types and proteins within the mini-brain spheres. The study also documents their integration with the neural tissues. Cross-sections under a transmission electron microscope, meanwhile, show that the capillaries are indeed hollow tubes that could transport blood.

Advertisement

"We've sketched on a few napkins together," she quipped.

The capillary networks are not as dense as they would be in a real brain, she acknowledged. The study also shows that they don't last longer than about a week or two.

New research

Aware of both their constraints and their potential, Hoffman-Kim's lab has already started experiments to take advantage of the presence of vasculature. Study second author Liana Kramer, a Brown senior, has begun looking at what happens to the vasculature and neural cells when mini-brains are deprived of oxygen or glucose. Later that same test bed could be used to examine the difference that different drugs or other treatments make.

"We can study a range of injury conditions, several drugs that are being tested and several conditions - such as stroke and diabetes - together," Hoffman-Kim said.

Source-Eurekalert