New proton channel called Otopetrin 1 (Otop1) discovered involves in the body's ability to maintain balance and helps detect sour taste.

‘Otopetrin 1 (Otop1) contributes to inner ear function and balance, and is involved in sensing acids as part of sour taste perception.’

Protons control whether a solution is acidic or basic. They set pH. Not surprisingly, protons do not cross cell membranes; they must be transported across the membrane through special proteins like ion channels. Although a gene encoding an ion channel that lets protons leave cells has been identified, whether one gene or several genes were necessary to form an ion channel that lets protons into cells was unknown.

Now, research into sour taste has identified the otopetrin family of genes as encoding proton-conducting ion channels.

This gene family was originally identified as important for balance: mice with mutations in otopetrin 1 (Otop1) are called tilted (tlt) because they cannot right themselves. The function of the encoded protein and why mutations in the gene cause a vestibular defect are unknown.

But while studying taste perception, a group led by Emily Liman, USC Dornsife professor of biological sciences, discovered that Otop1 encodes a proton channel, providing hints as to how otopetrin1 contributes to inner ear function and balance.

Advertisement

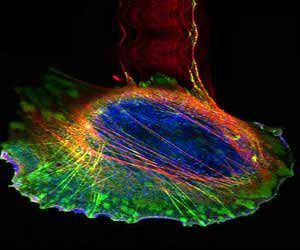

Indeed, eight years ago, her lab used biophysical approaches to show that protons enter taste cells through a specialized proton channel in the cell membrane. The gene encoding this channel and the structural properties of the proton channel were unknown.

Advertisement

Graduate student Yu-Hsiang Tu then tested candidate genes one-by-one until he found one that produced a proton-conducting protein when introduced into cells that did not have any proton-conducting channels.

After Yu-Hsiang had tested more than three dozen candidates, Liman had all but given up. "When Yu-Hsiang called me in to the lab and showed me the otopetrin data, I could not believe we had finally found it," Liman said. "We had been looking for so many years."

In addition to Otop1, there are two other related genes in vertebrates (Otop2 and Otop3), and this gene family is represented in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster.

Otopetrins are structurally different from all other ion channels, and all of the otopetrins form proton channels, suggesting that these proton-conducting channels are evolutionarily conserved. Each of the otopetrins has a distinct distribution in many tissues, including the tongue, ear, eye, nerves, reproductive organs, and digestive tract.

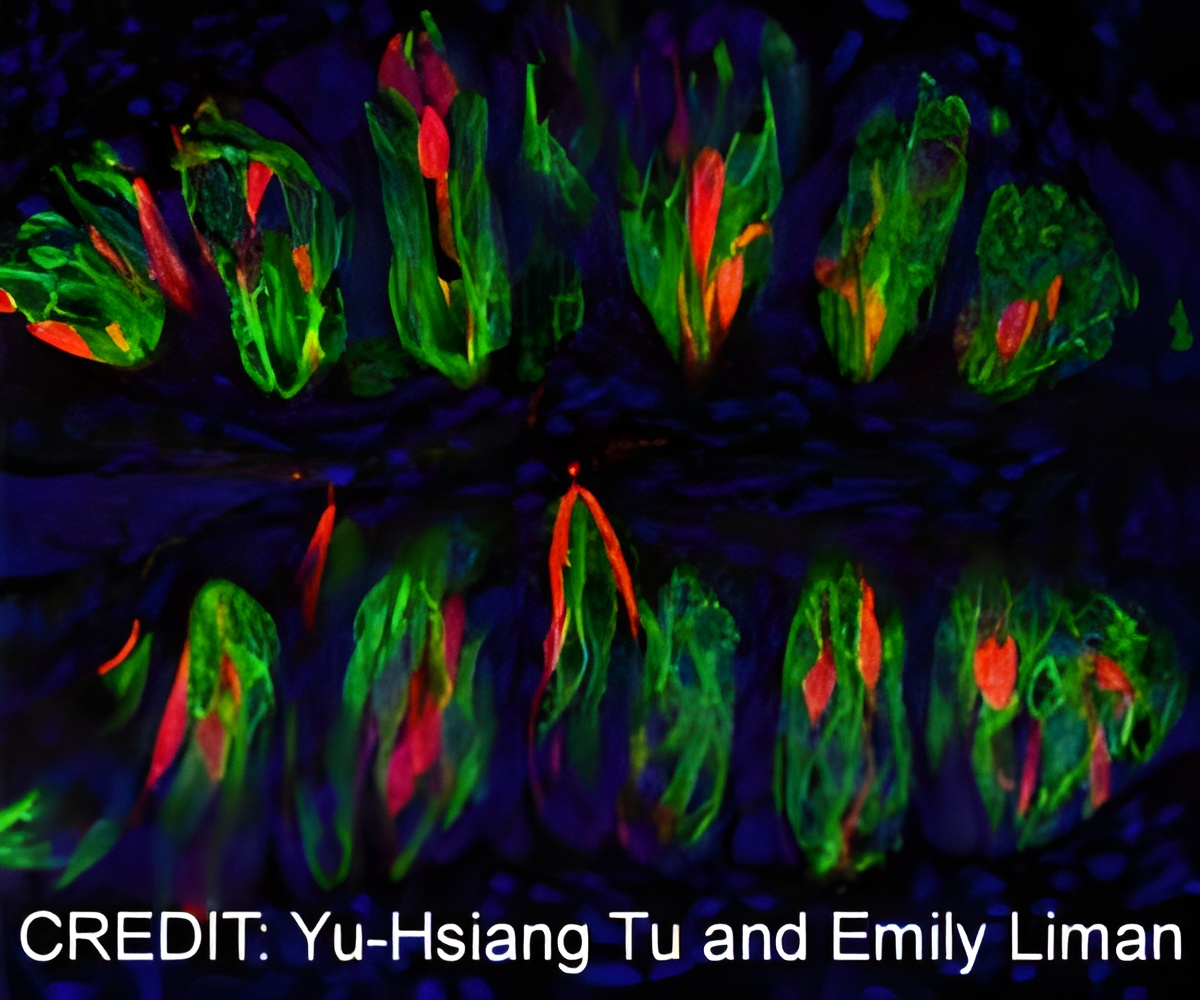

In the vestibular system, Otop1 is necessary for the formation and function of structures called otoconia, which are calcium carbonate crystals that sense gravity and acceleration.

The investigators speculate that the otopetrins maintain the pH appropriate for formation of otoconia and that the defect in the tlt mice is due to a dysregulation of pH.

In the taste system, otopetrins may be involved in sensing acids as part of sour taste perception. The function of these proton channels in other tissues is unknown.

"We never in a million years expected that the molecule that we were looking for in taste cells would also be found in the vestibular system," Liman said. "This highlights the power of basic or fundamental research."

Source-Eurekalert