Blocking the protein ATR has anti-tumor effects in several animal models of cancer, such as an aggressive type of acute myeloid leukemia and Ewing sarcoma.

‘Blocking the protein ATR has anti-tumor effects in several animal models of cancer, such as an aggressive type of acute myeloid leukemia and Ewing sarcoma.’

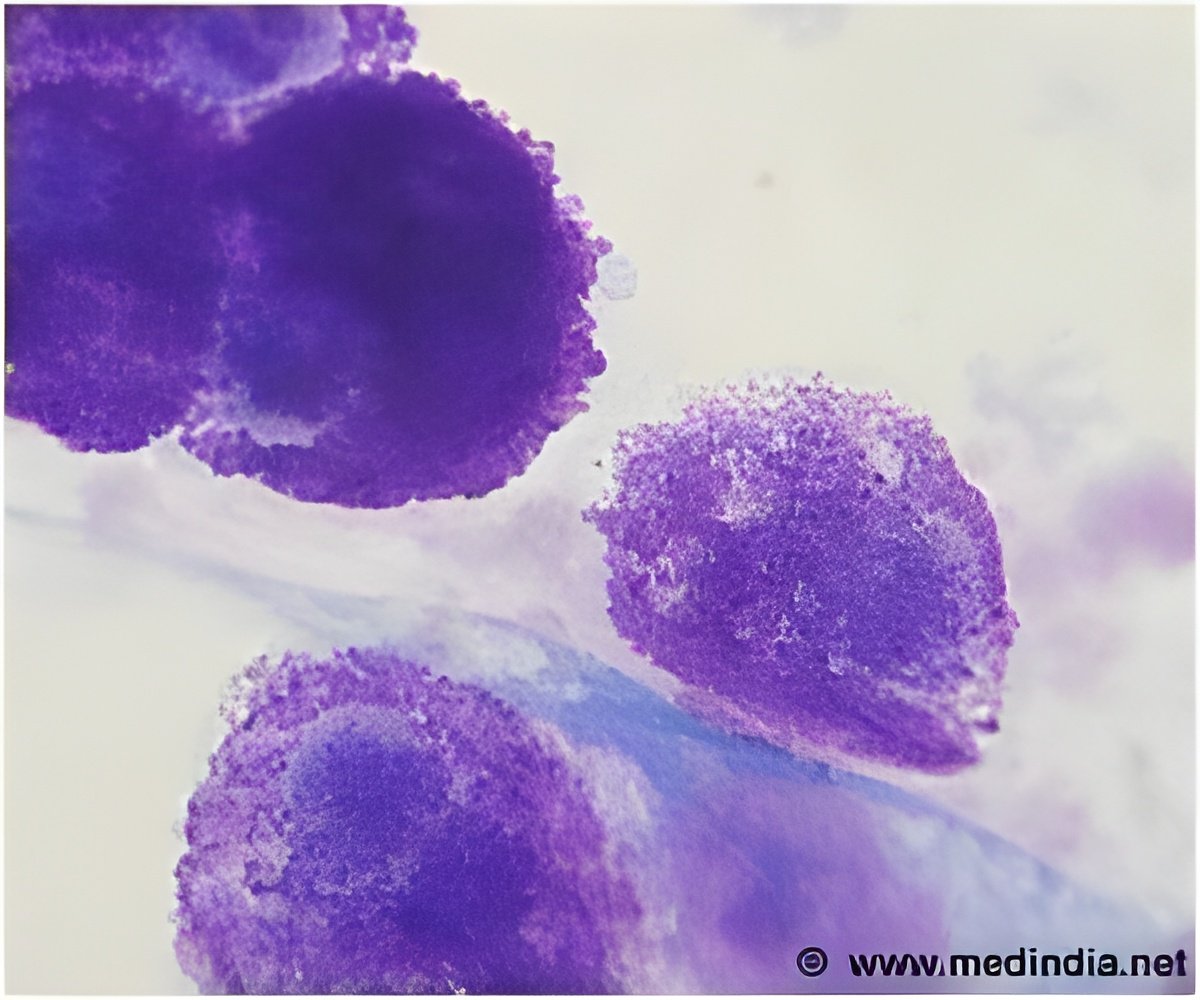

Tumors are an accumulation of cells that divide without control, accumulating hundreds of chromosomal alterations and mutations in their DNA. These alterations are triggered in part by a type of damage to the DNA known as replicative stress. To survive in the face of this chaos, tumor cells need the intervention of the damage response protein ATR, known for its role as guardian of genome integrity, to which they become addicted. The work performed by Fernandez-Capetillo's team was premised on the assumption that if tumors suffer from high levels of replicative stress, they could be particularly sensitive to treatments with drugs that inhibit ATR, since this protein is responsible for reducing this type of stress. In addition, as healthy cells hardly suffer from this type of stress, the effects on those cells would be limited. The researcher explains it as follows, "If you eliminate a fireman [ATR] in a town where there is no fire [healthy cells] nothing happens, but if you do the same in a town where there is a fire [tumor cells with greater damage to their DNA than healthy cells], the fire will spread and destroy the town".

In 2011, Fernandez-Capetillo's team proved that it was on the right track. In two independent papers published in the prestigious journal Nature Structural & Molecular Biology they reported, for the first time, that blocking ATR was particularly toxic to tumor cells; a conclusion they reached by using cell cultures and genetic mouse models.

Having made this conceptual breakthrough, "the next step was to focus on finding tumors that presented the greatest replicative stress levels, because we believe that these are the type that will benefit most from this new therapy", says Fernandez-Capetillo.

According to data published by the laboratory itself, tumors with high replicative stress levels tend to have high levels of CHK1 protein - also involved in suppressing replicative stress - to survive in these adverse conditions. "This suggested that one way of identifying tumors with high levels of replicative stress was simply to determine how much CHK1 was present", explains Fernandez-Capetillo. Consequently, after analysing CHK1 levels in a broad panel of human tumors, the researchers identified two types with very large quantities of this protein: Ewing sarcoma and several types of lymphoma and leukemia, including acute myeloid leukemia.

Advertisements

In the case of Ewing sarcoma, ATR inhibitors showed a very high toxicity level, both on culture plates as in the animal models with tumor grafts. "The response observed is better than that reported for other agents that are currently undergoing clinical testing, suggesting that these compounds are an alternative for the future".

Advertisements