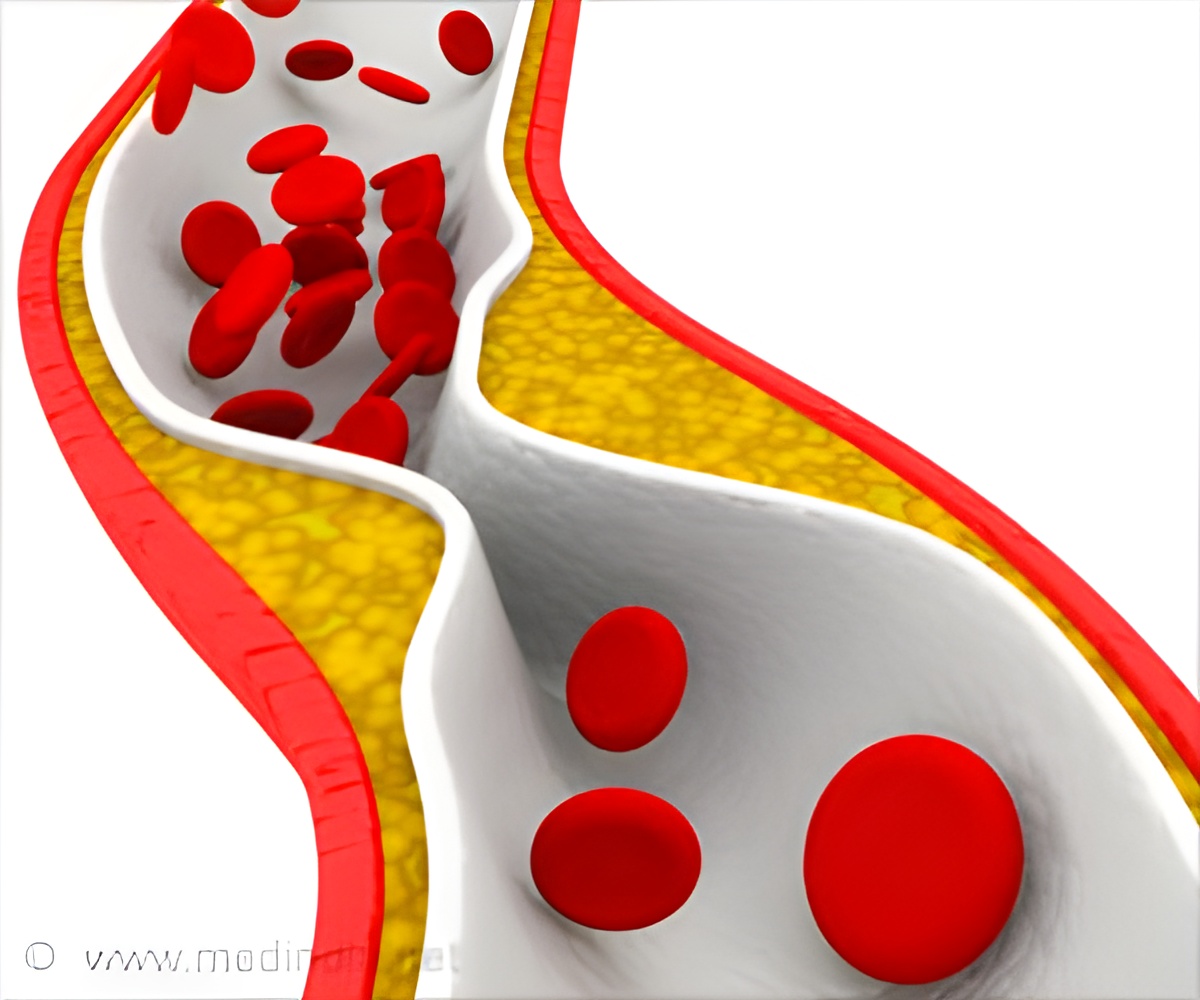

Atherosclerosis is a disease in which plaque builds up inside arteries, and a nanoparticle can simultaneously light up and treat atherosclerotic plaques.

TOP INSIGHT

Magnetic resonance imaging offers a potential approach for plaque visualization, but requires the use of a contrast agent to show the atherosclerotic plaques clearly.

Current detection strategies often fail to identify dangerous plaques, which can clog arteries over time or break off from arterial walls and block blood flow, causing a heart attack or stroke. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) offers a potential approach for plaque visualization, but requires the use of a contrast agent to show the atherosclerotic plaques clearly. But the potential for harmful immune reactions still exists with the use of donor-derived HDL.

Beyond imaging, there is a therapeutic aspect of using HDL. HDL is widely known as "good" cholesterol because of its ability to pull low-density lipoprotein, or "bad" cholesterol, out of plaques. This process shrinks the plaques, making them less likely to clog arteries or break apart.

To simultaneously identify and treat atherosclerosis without triggering an immune response, Dhar and Bhabatosh Banik, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in her lab, created an MRI-active HDL mimic. The researchers, who are at the University of Georgia, Athens, had previously built synthetic HDL particles lacking a contrast agent. These particles lowered levels of total cholesterol and triglycerides in mice.

"The key challenge, then, was designing the contrast agent," Banik says. "It took time to figure out the optimal lipophilicity and solubility." The contrast agent, iron oxide, needs to be encapsulated in the synthetic lipoparticle's hydrophobic core to provide the brightest possible signal. Eventually, the researchers hit on the right chemical combination - iron oxide with a fatty surface coating - for optimal particle encapsulation. They successfully visualized the contrast agent using MRI in cell studies.

The researchers targeted macrophages by decorating the nanoparticles' surfaces with a molecule that selectively binds to macrophages. The team observed that the nanoparticles were engulfed by these white blood cells. "Then, when the macrophages ruptured, which is a sign of an unstable plaque, the cells spit out the nanoparticles, causing the MRI signal to change in a detectable fashion," Banik says. Dhar says her lab is now using MRI to study how well the particles light up and treat plaques in animals, and she hopes to begin clinical trials within two years.

MEDINDIA

MEDINDIA

Email

Email