When parasites that have not been treated with drugs are mixed with their drug-resistant counterparts, they could reduce the incidence of drug-resistance overall.

‘When parasites from host populations that have not been treated with drugs mix with their drug-resistant counterparts in the general population, they could reduce the incidence of antibiotic resistance overall, which may help prolong a drug's effectiveness.’

The research, just published in Biology Letters, offers a way to assess when such an approach is likely to work - information that could help in the increasingly urgent hunt for alternatives to the current suite of parasite-fighting drugs. Andrew Park, an associate professor in the UGA Odum School of Ecology and College of Veterinary Medicine, who led the research, said, "Once resistance emerges, you might squeeze a little bit of life out of a drug by tweaking it, but often, very quickly, that entire class of drugs will become useless. Right now, we're really struggling to manage diseases like MRSA and extensively drug-resistant TB. We're at a point where new classes of drugs don't grow on trees anymore; it can take 15 to 20 years to develop them. It's a challenge just to keep pace. Refugia represent a management strategy that's being considered as a way to slow down the development of drug resistance, particularly in animal health."

Park and his colleagues created a model to predict the effects of refugia on two important outcomes- the overall prevalence of infection within a population and the proportion of those infections that are drug-resistant.

The model incorporates two main variables. One is the level of drug coverage - the proportion of the overall population that has been treated against parasites. The other is the degree of mixing between the treated and untreated groups.

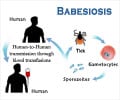

In the case of a disease like heartworm, which is transmitted by mosquitoes and infects both wild animal populations and companion animals, there is some natural variation in both drug coverage and mixing. Both variables can also be controlled, to an extent.

Advertisement

The model yielded predictions about how changing the levels of drug coverage and mixing would affect prevalence and resistance, and also shed light on the evolutionary processes at work.

Advertisement

Park said that his team's model serves as a general outline for considering the use of refugia as a management strategy, providing a blueprint for future models to predict outcomes in specific host-parasite systems.

Park said, "With refugia, the idea is to dilute overall drug resistance. We can say, yes, we're putting parasites into the population, but they're the right kind of parasites, and in some cases that may be better than having it just flooded with the wrong kind of parasites that we can never treat. But we need this kind of model to understand all these interactions in order to know when that's a good idea."

Source-Eurekalert