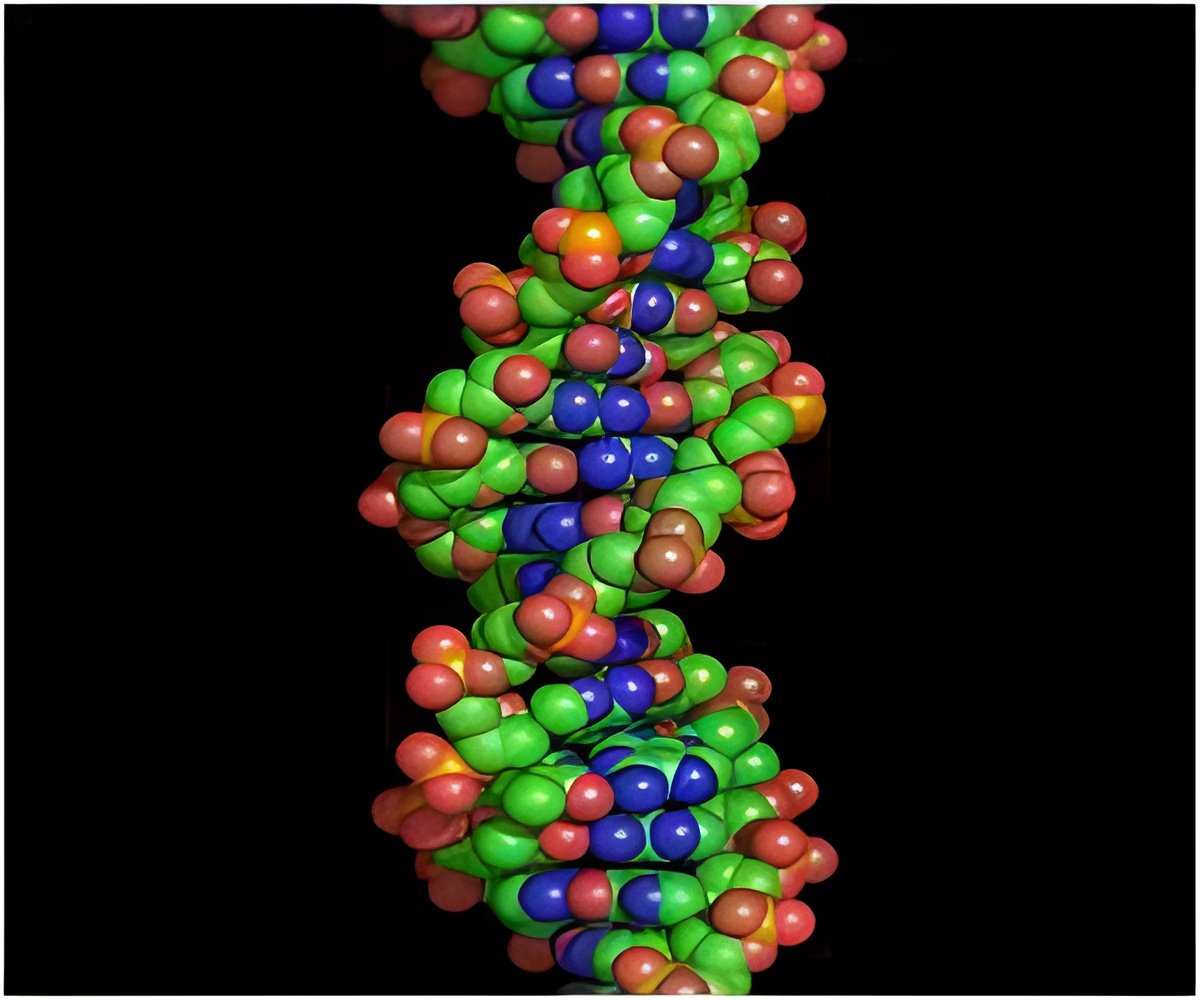

Researchers have found that genetic differences between the DNAs of unrelated patients and donors are the reason for high rates of acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD)

Bone marrow and stem cell transplants are used to treat a variety of malignant blood diseases such as leukemia. Hematopoietic cell transplantation was pioneered at the Hutchinson Center in the 1970s and continues to be a major focus of research and clinical trials to improve survival and reduce side effects.

Published recently in Science Translational Medicine, the study details how researchers identified two specific single-nucleotide polymorphisms, also called SNPs (pronounced "snips"), within the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) in human DNA that are markers for either acute GVHD or disease-free survival. These markers are distinct from the human leukocyte antigens (HLA), found on the same chromosome as the MHC, that are traditionally used to match recipients and donors, a process called tissue typing.

Researchers found that if a patient and donor have different SNPs, the patient was at increased risk of GVHD or a lower chance of disease-free survival. The scientists surmised that genes located near these SNPs must be involved in that process.

"The question I wanted to ask with this study is whether there could be genes we don't know about that are located close to the major histocompatibility complex that could be influencing GVHD risk," said Petersdorf, a member of the Hutchinson Center's Clinical Research Division. "Now that we know what to test for we can begin screening for the presence of the SNPs in patients and donors and select the optimal donor whose SNP profile will benefit the patient the most."

SNP genotyping is only beneficial for patients when they have multiple matched unrelated donors in order to determine which donor is the optimal match. Fortunately, this is fairly common, according to the study. Of 230 patients who had two or more HLA-matched donors, significant percentages also had at least one donor who was SNP-matched.

The next step for researchers is to sequence the MHC region of genes close to the SNP locations in order to identify which genes are directly responsible for the correlations of survival and GVHD.

For this study, researchers conducted a retrospective discovery-validation study that examined DNA from more than 4,000 former transplant patients nationwide. They studied 1,120 SNPs in the MHC on chromosome 6 – the region where all tissue typing and immune function genes are densely packed. They narrowed those SNPs to two that appeared to correlate with disease-free survival and acute GVHD.

Source-Eurekalert

MEDINDIA

MEDINDIA

Email

Email