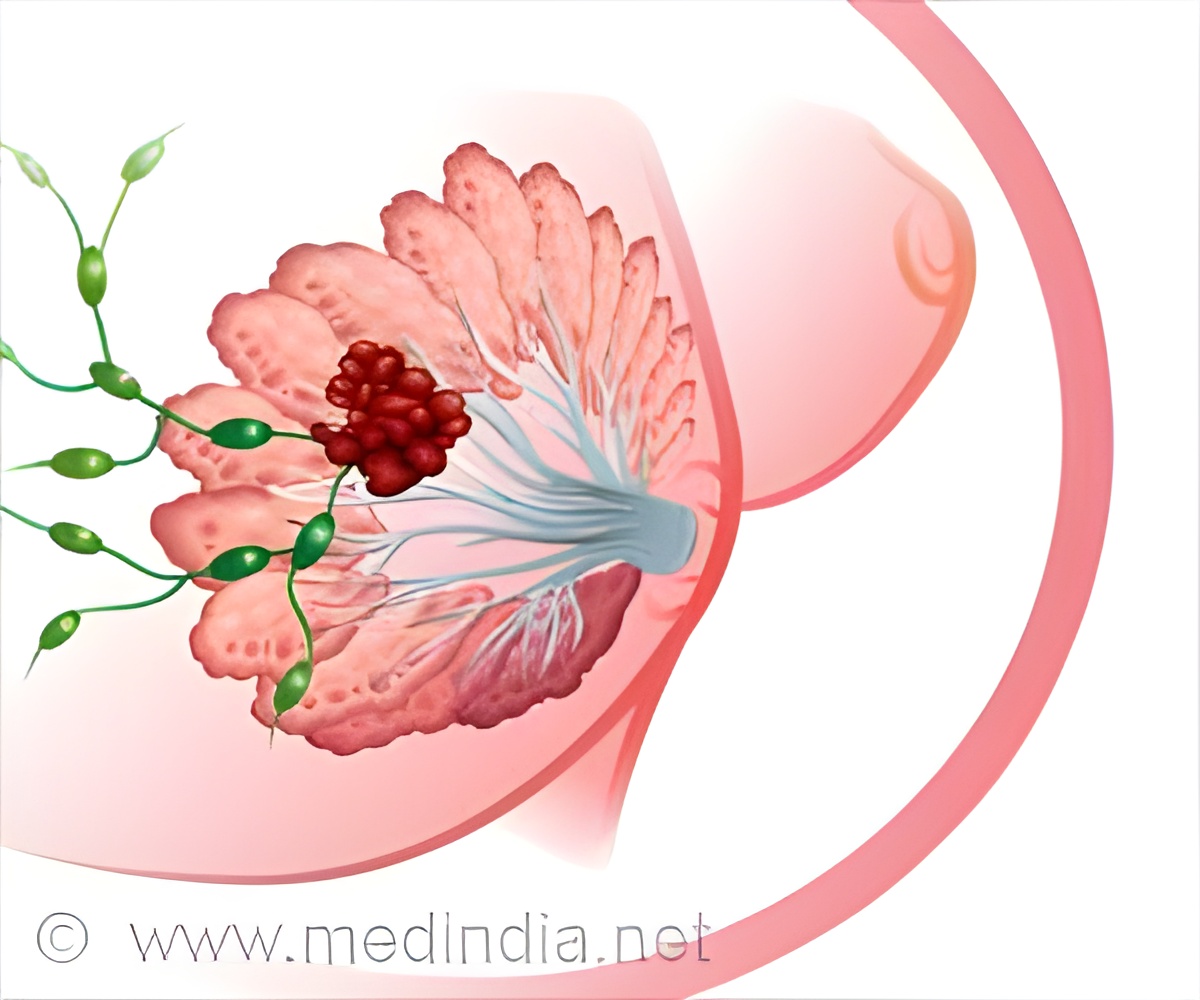

Delays in diagnosis of breast cancer in low-income and ethnic minority women in Chicago as a result of under-sourced health centers.

TOP INSIGHT

Women from low-income and ethnic minority population received mammograms and diagnostic follow-up at unaccredited facilities.

Richard Warnecke and his colleagues found that when compared with white patients, black and Hispanic patients were more likely to be diagnosed at disproportionate share facilities (37 percent and 47 percent vs. 11 percent, respectively); to be referred to more than one facility (36 percent and 47 percent vs. 26 percent); and to experience a diagnostic delay in excess of 60 days (27 percent and 32 percent vs. 12 percent). Black and Hispanic patients were less likely to be diagnosed at a facility designated as a Breast Imaging Center of Excellence, or BICOE, (46 percent and 49 percent vs. 81 percent) and less likely to have their breast cancer initially detected through screening (47 percent and 42 percent vs. 59 percent).

“Low-income and racial and ethnic minority patients, largely residing in medically underserved communities on the south and west sides of the city, often received their care in under-resourced hospitals and public health clinics,” said Richard Warnecke, professor emeritus of epidemiology, public administration and sociology. “On the other hand, residents of the more racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically diverse north and east sides were more likely to receive their care at academic and high volume health centers.

“Time is of the essence, particularly for young women of color who are at greater risk for aggressive breast cancer when compared with white women. A patient’s delay in diagnosis and treatment often results when the referral hospitals are not properly equipped to assist them and they may have to be referred several times before diagnostic resolution,” said Warnecke, who is also a researcher at the UIC Institute for Health Research and Policy and the University of Illinois Cancer Center.

At the time of the research, Chicago had 11 full-service or academic facilities that were designated a BICOE, but many patients received mammograms and diagnostic follow-up at unaccredited facilities, Warnecke said.

Not only were minority women often forced to travel outside of their neighborhoods when recommended for diagnostic follow up and treatment, but their choice of health care centers may have been limited by insurance, a primary factor of access to care, Warnecke said.

Co-authors on the paper are Richard Campbell, Ganga Vijayasiri, Richard Barrett and Garth Rauscher of UIC. Like Warnecke, Rauscher is also a member of the UI Cancer Center.

Source-Newswise

MEDINDIA

MEDINDIA

Email

Email