Novel role for the inhibition in cerebellar plasticity and behavior has been discovered by a team of researchers.

TOP INSIGHT

In the cerebellum, motor learning can occur along a continuum and what seems to be the key, is the influence of an inhibitory cell class called molecular layer interneurons.

In a recent publication in Neuron, researchers from the lab of Dr. Jason Christie, Research Group Leader at the Max Planck Florida Institute for Neuroscience (MPFI), have discovered part of the answer to this longstanding question. Dr. Christie's team has broadened the current understanding of neural computation and provided fundamental insights into the mechanisms and principles underlying motor learning.

"Learning isn't a monolithic event, that either happens or doesn't," describes Dr. Christie. "It's a much more complex behavior that can vary in duration, magnitude and direction.

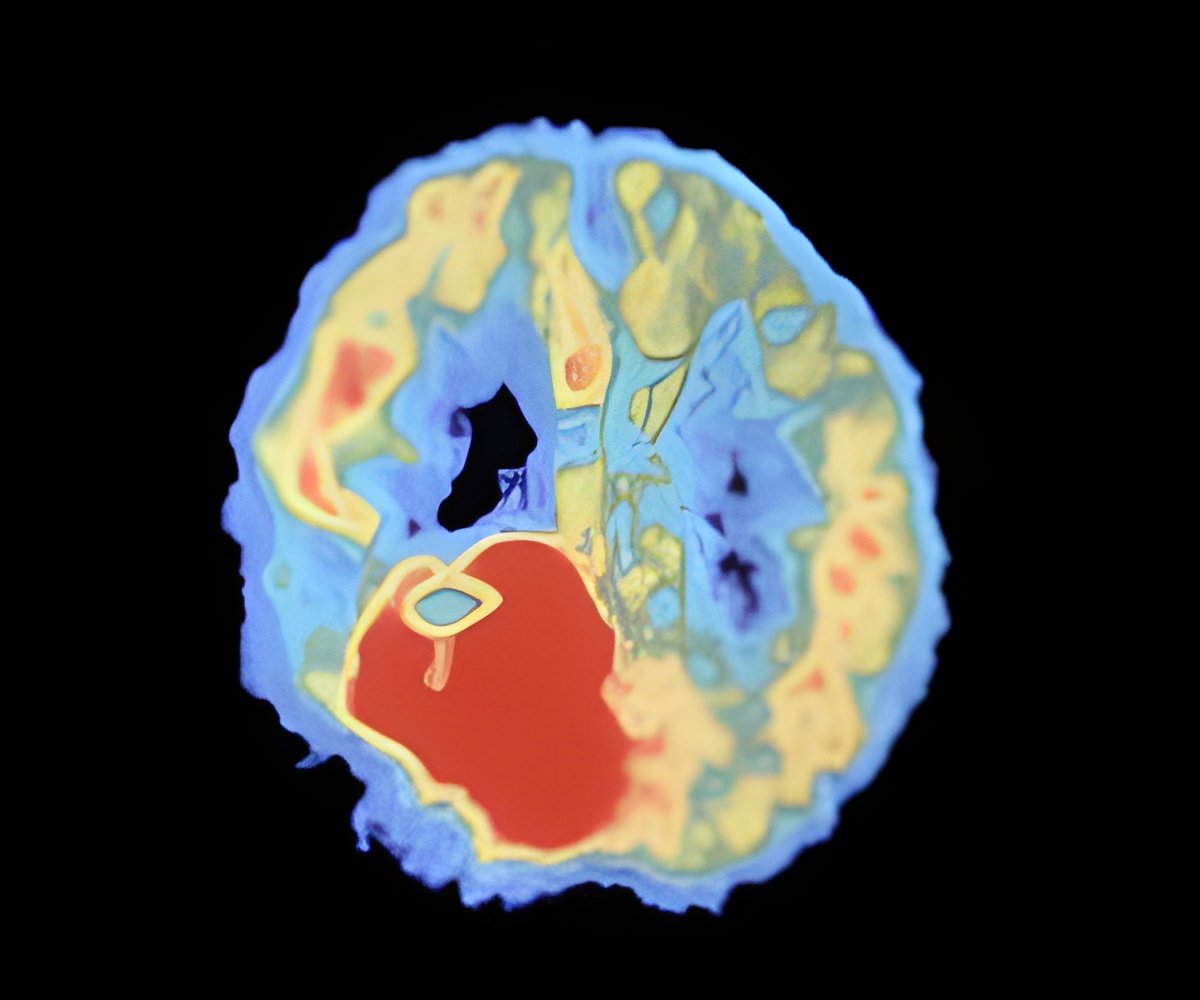

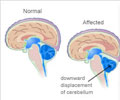

An anatomically unique region of the brain, the cerebellum plays a critically important role in regulating motor control and coordination. Despite its relatively small size- only about 10% of the entire brain- the cerebellum houses roughly half of our total neurons, around 50 billion. While receiving many inputs from various regions of the brain, the cerebellum integrates and sends refined information out through a single type of specialized neuron called a Purkinje cell. These cells receive two well characterized excitatory inputs and a lesser studied inhibitory input, helping to guide motor behavior and facilitate learning.

"Thousands of excitatory inputs by parallel fibers, set the stage for Purkinje cell activation by providing sensory and motor context for actions," describes Audrey Bonnan, a Postdoctoral Researcher in the Christie Lab and one of the publication's first authors. "It's these inputs that activate Purkinje cells and maintain normal coordination and movement. When we make a mistake however, a second excitatory input from a climbing fiber, arrives simultaneously and delivers an instructive signal. This new information detailing motor error, weakens the synaptic connections between parallel fibers and Purkinje cells; producing a change in behavior and ultimately allowing for learning to occur. But the function of inhibitory inputs in this process, was still largely unknown."

"We found that inhibition allows for an entire spectrum of outcomes," notes Dr. Christie. "Without inhibition, Purkinje cells showed the expected synaptic weakening caused by co-activation of parallel fibers and climbing fibers. By strongly activating molecular layer interneurons, there was a complete reversal of plasticity where synapses were strengthened with the addition of inhibition. Surprisingly with weak activation of these interneurons, plasticity seemed to be negated where no change occurred at all."

"Inhibition seems to dramatically broaden the range with which cells can respond to stimuli," explains Dr. Christie. "Instead of the brain having only two options -learning or not learning- there can be a tremendous amount of variation in between. For example, learning a little or learning a lot. It's like black and white versus shades of gray, where the shades of gray allow for a greater amount of behavioral flexibility."

Dr. Christie notes that the work was a tremendous effort between first authors Matt Rowan, Ph.D., now an Assistant Professor at Emory University; Audrey Bonnan, Ph.D., and Ke Zhang, a graduate student in the International Max Planck Research School for Brain and Behavior, and that their surprising findings have opened up a whole new avenue of inquiry for the future.

Source-Eurekalert

MEDINDIA

MEDINDIA

Email

Email