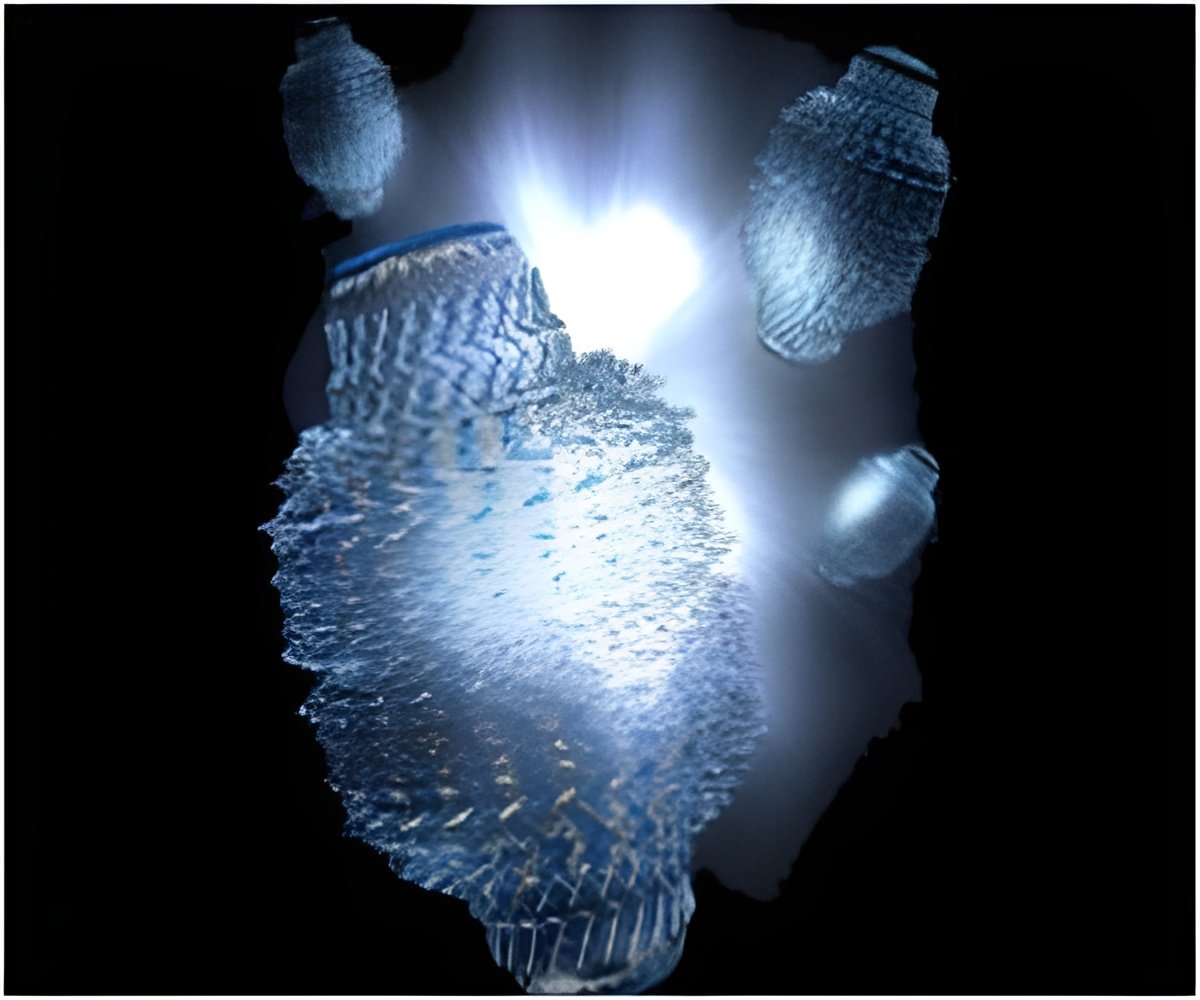

Nanoshells could deliver more chemotherapy drugs with fewer side effects. Laser-activated gold nanoparticles trigger the release of drugs inside cancer cells.

‘This combined method could provide temporally localized drug-release strategies that can facilitate high local concentrations of chemotherapy drugs deliverable at a specific treatment site.’

Though the tests were conducted with cell cultures in a lab, the research was designed to demonstrate clinical applicability: The nanoparticles are nontoxic, the drugs are widely used and the low-power, infrared laser can noninvasively shine through tissue and reach tumors several inches below the skin."In future studies, we plan to use a Trojan-horse strategy to get the drug-laden nanoshells inside tumors," said Naomi Halas, an engineer, chemist and physicist at Rice University who invented gold nanoshells and has spent more than 15 years researching their anticancer potential. "Macrophages, a type of white blood cell that's been shown to penetrate tumors, will carry the drug-particle complexes into tumors, and once there we use a laser to release the drugs."

Co-author Susan Clare, a research associate professor of surgery at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, said the PNAS study was designed to demonstrate the feasibility of the Trojan-horse approach. In addition to demonstrating that drugs could be released inside cancer cells, the study also showed that in macrophages, the drugs did not detach prior to triggering.

"Getting chemotherapeutic drugs to penetrate tumors is very challenging," said Clare, also a Northwestern Medicine breast cancer surgeon. "Drugs tend to get pushed out of tumors rather than drawn in. To get an effective dose at the tumor, patients often have to take so much of the drug that nausea and other side effects become severe. Our hope is that the combination of macrophages and triggered drug-release will boost the effective dose of drugs within tumors so that patients can take less rather than more."

If the approach works, Clare said, it could result in fewer side effects and potentially be used to treat many kinds of cancer. For example, one of the drugs in the study, lapatinib, is part of a broad class of chemotherapies called tyrosine kinase inhibitors that target specific proteins linked to different types of cancer. Other Federal Drug Administration-approved drugs in the class include imatinib (leukemia), gefitinib (breast, lung), erlotinib (lung, pancreatic), sunitinib (stomach, kidney) and sorafenib (liver, thyroid and kidney).

Advertisement

Halas invented nanoshells at Rice in the 1990s. About 20 times smaller than a red blood cell, they are made of a sphere of glass covered by a thin layer of gold. Nanoshells can be tuned to capture energy from specific wavelengths of light, including near-infrared (near-IR), a nonvisible wavelength that passes through most tissues in the body. Nanospectra Biosciences, a licensee of this technology, has performed several clinical trials over the past decade using nanoshells as photothermal agents that destroy tumors with infrared light.

Advertisement

In the latest study, Goodman contrasted the use of continuous-wave laser triggering and triggering with a low-power pulse laser. Using each type of laser, she demonstrated the remotely triggered release of drugs from two types of nanoshell-drug conjugates. One type used a DNA linker and the drug docetaxel, and the other employed a coating of the blood protein albumin to trap and hold lapatinib. In each case, Goodman found she could trigger the release of the drug after the nanoshells were taken up inside cancer cells. She also found no measurable premature release of drugs in macrophages in either case.

Halas and Clare said they hope to begin animal tests of the technology soon and have an established mouse model that could be used for the testing.

"I'm particularly excited about the potential for lapatinib," Clare said. "The first time I heard about Naomi's work, I wondered if it might be the answer to delivering drugs into the anoxic (depleted of oxygen) interior of tumors where some of the most aggressive cancer cells lurk. As clinicians, we're always looking for ways to keep cancer from coming back months or years later, and I am hopeful this can do that."

Source-Eurekalert