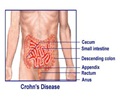

Abundant microbe populations have been thought to have roles in obesity, diabetes and inflammatory bowel diseases such as Crohn's disease.

TOP INSIGHT

Microbes in the intestines play a key role in predicting the severity of the disease in individuals with inflammatory bowel disease.

In a telling sequence, one bacterial species, Vibrio, drew numerous neutrophils, which indicated a rapid inflammatory response in one fish. Another species, Shewanella, inserted into a separate germ-free fish barely attracted an immune response. In a third germ-free fish, both species were introduced together and assembled with a ratio of 90- percent Vibrio to 10-percent Shewanella. The inflammatory response in the third fish was completely controlled by the low-abundance species.

"Until now, we've only been able to capture proportional information, like you'd see displayed in a pie graph, of the makeup of various microbiota, in percentages of their abundance. Biologists in this field have typically assumed an equal contribution based on that makeup," said Rolig.

Low counts of a bacterial species generally have been discounted in importance, but slight shifts in the ratios of abundant microbe populations have been thought to have roles in obesity, diabetes and inflammatory bowel diseases such as Crohn's disease.

That thinking is now changing, Rolig said. "The contribution of each bacterium is not equal. There is a per-capita effect that needs to be considered."

"Now we've shown that these minor members can have a major impact. If we can identify these keystone species, and find that in a disease state one species may be missing, we might be able to go in with a specific probiotic to restore healthy functioning," said Rolig, who also is a scientist in the National Institutes of Health-funded Microbial Ecology and Theory of Animals Center for Systems Biology, known as the META Center, at the UO.

"I'm really proud of this paper because it exemplifies an achievement of one of the major goals of the META Center for Systems Biology, namely to provide a predictive model of how host-microbe systems function. This experimental and modeling framework could be readily generalized to more complex systems such as humans, for example to predict disease severity in individuals with inflammatory bowel disease based on the pro-inflammatory capacity of their gut microbes as assayed in cell culture," said Guillemin.

Source-Eurekalert

MEDINDIA

MEDINDIA

Email

Email