New study from MIT demonstrates the exact role cholesterol plays in releasing the flu virus.

TOP INSIGHT

The new findings do not have any direct implications for vaccinating or treating flu, although they could inspire new research into how to prevent viral budding.

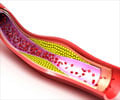

While previous research had demonstrated that M2's action during budding was dependent on cholesterol concentrations in the cell membrane, the new study demonstrates the exact role cholesterol plays in releasing the virus.

And although the team focused on a flu protein in their study, "we believe that with this approach we have developed, we can apply this technique to many membrane proteins," says Mei Hong, an MIT professor of chemistry and senior author of the paper, which appears in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences the week of Nov. 20.

The amyloid precursor protein and alpha-synuclein, implicated in Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease, respectively, are among the proteins that spend at least some of their lifetimes within cell membranes, which contain cholesterol in their fatty layers, Hong says.

"About 30 percent of proteins encoded by the human genome are associated with the cell membrane, so you're talking about a lot of direct and indirect interactions with cholesterol," she notes. "And now we have a tool for studying the cholesterol-binding structure of proteins."

Earlier imaging and experimental studies showed that flu's M2 protein was necessary for viral budding, and that the budding worked best in cell membranes containing a specific concentration of cholesterol. "But we were curious," Hong says, "about whether cholesterol molecules actually bind or interact with M2. This is where our expertise with solid-state NMR comes in."

The NMR technique allowed Hong and her colleagues to pin down cholesterol "in its natural environment in the membrane, where we also have the protein M2 in its natural environment," she says. The team was then able to measure the distance between cholesterol atoms and the atoms in the M2 protein to determine how cholesterol molecules bind to M2, as well as cholesterol's orientation within the layers of the cell membrane.

Cholesterol and membrane curvature

Cholesterol isn't evenly distributed throughout the cell membrane -- there are cholesterol-enriched "rafts" along with less enriched areas. The M2 protein tends to locate itself at the boundary between the raft and nonraft areas in the membrane, where the budding virus can enrich itself with cholesterol to build its viral envelope. The new findings do not have any direct implications for vaccinating or treating flu, although they could inspire new research into how to prevent viral budding, Hong says.

The configuration that Hong and her colleagues observed at the budding neck -- two cholesterol molecules attached to M2 -- creates a significant wedge shape within the inner layer of the cell membrane. The wedge produces a saddle-shaped curvature at the budding neck that is needed to sever the membrane and release the virus.

Source-Eurekalert

MEDINDIA

MEDINDIA

Email

Email