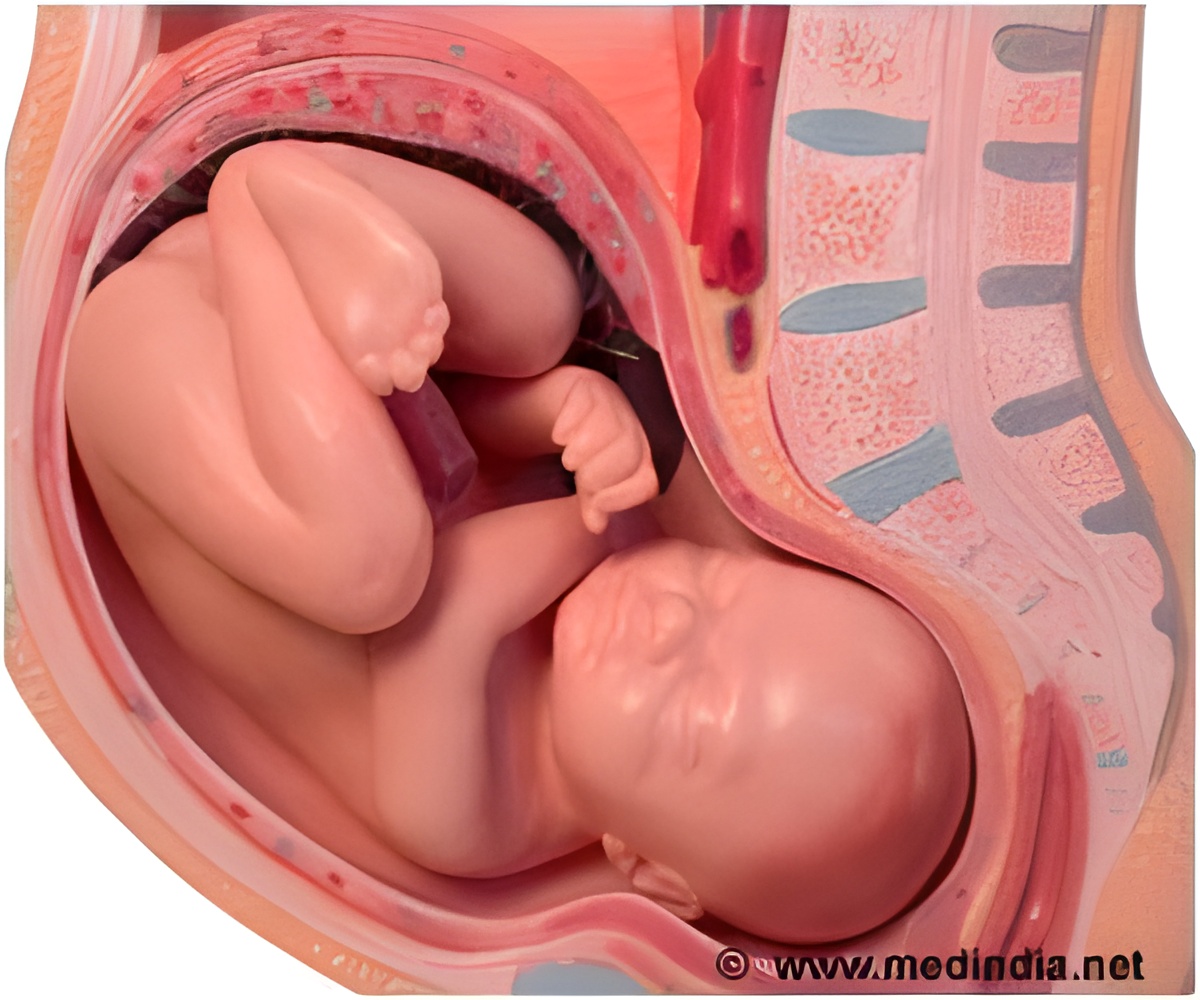

Children conceived during the Dutch famine show that the regulatory systems of their growth genes are altered, which also explains their predisposition for metabolic disease later.

The research team compared the DNA of these children, now aged 60, at 1.2 million CpG methylation sites comparing them with same-sex siblings not exposed to famine. They noticed that the groups of genes involved in growth and development showed a different gene activity setting in these famine struck children as compared with their siblings with a similar genetic and familial background. The potential for a gene to become active is mainly determined in the crucial weeks post fertilization.

L.H. Lumey, MD, associate professor of Epidemiology at Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health and senior author who collected the analyzed blood samples said, "Looking at the human genome we see systematic changes in gene regulation during early human development in response to the environment. The epigenetic revolution has given us the tools to investigate these changes and look at the impact for later life.”

The study is published in the journal Nature Communications.

Source-Medindia

MEDINDIA

MEDINDIA

Email

Email