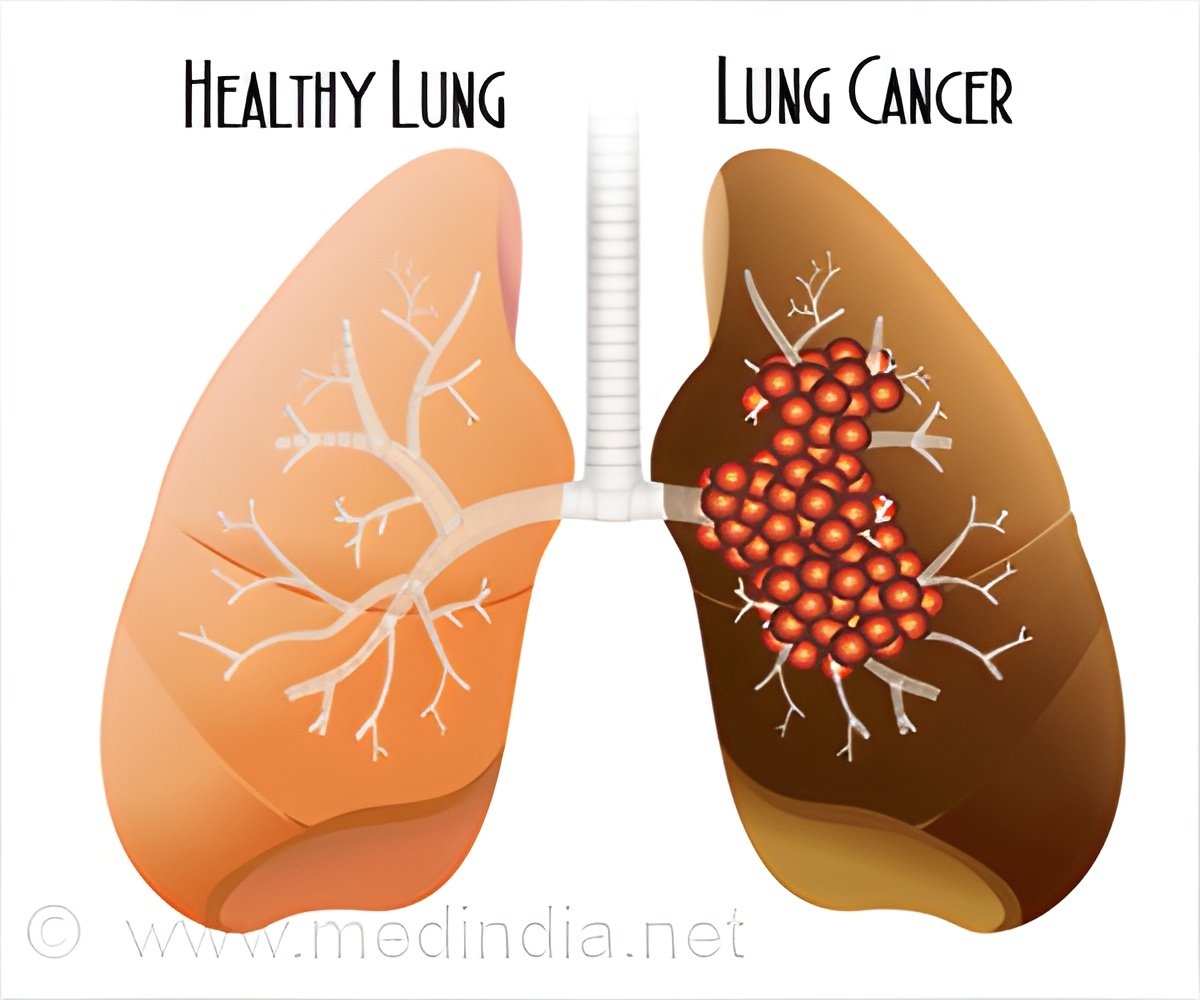

Secondary analysis with a different test is required to verify results to treat patients with ROS1-positive lung cancer.

‘The strategy of testing two methods to confirm ROS1-positive lung cancer patients helps the doctor in precise diagnosis and treatment.’

"The main point is to be aware of the deficiencies in these assays and not always to trust a negative result from a single test. If you're suspicious that a patient could be ROS1-positive - maybe they're a never-smoker without other known drivers such as EGFR, ALK, KRAS, BRAF - then it may be useful to try another kind of test," says Kurtis Davies, PhD, Lead Assay Development Scientist at the Colorado Molecular Correlates Laboratory (CMOCO).Davies, the study's first author, worked closely with colleagues including senior authors Robert C. Doebele, MD, PhD, director of the CU Cancer Center Thoracic Oncology Research Initiative, and Dara Aisner, MD, PhD, CMOCO Director in the CU Department of Pathology, which routinely employs multiple modes of testing cancer specimens. "The University of Colorado has been a big player in the clinical research of ROS1 lung cancer, and so we have a lot more ROS1-positive samples than almost anywhere else. This allowed us to go back to our large bank of samples to test them in these three ways," Davies says.

The study found that each test has inherent deficiencies. ROS1-positive cancers are caused by the gene ROS1 fusing with one of some partner genes. One of these possible partners sits very near to ROS1 on chromosome 6. When ROS1 fuses with this nearby partner, there may not be enough DNA deleted to identify the fusion using FISH.

"It can leave enough of the FISH probe binding sites that the sample appears normal even though a ROS1 fusion is present," Davies says. The deficiency in the DNA-based test was due to the inherent inability to correctly sequence large areas of the ROS1 gene.

"You have large swaths of un-sequenced DNA, and if the ROS1 change is in one of those areas, it's possible to miss it," Davies says.

Advertisement

Unlike the other two tests, the assay based on RNA doesn't attempt to take a snapshot of altered ROS1 DNA. Instead, it looks at what is manufactured from the DNA. This means that an RNA-based assay has the potential to more directly test for the results of ROS1 gene fusion that can drive cancer. That is, as long as you have good enough RNA.

Advertisement

On the plus side, pathologists looking at the assay data can tell if RNA is of high enough quality to believe test results. ("We know when RNA quality is low," Davies says.) In these cases, the FISH or DNA test could be used. And the false-negatives attributed to the RNA assay in this study were all due to low RNA quality.

"If you take out the negatives due to RNA quality (which we don't regard as negative), there were no false negatives with this kind of test," Davies says.

Again, according to Davies, the takeaway is to realize there is no perfect test and sometimes secondary analysis with a different test is necessary to confirm results. The strategy is more than theory.

"We've run FISH concurrently with the RNA test for the past 18 months," Davies says. "This helps us to provide every reassurance that we are not missing patients who can benefit from ROS1 directed therapy."

The strategy of testing by two methods has paid off.

"One of the patients included in this study was initially determined to be ROS1-negative via FISH, but was subsequently shown to be ROS1-positive via RNA," Aisner says. "This patient went on to receive ROS1 targeted therapy and demonstrated an impressive response."

Source-Eurekalert