Safe driving cannot be predicted even if a driver has passed the motor vehicle administration's vision test.

"Optical blur and cataracts are very common and lots of people with these conditions continue to drive," said author Joanne Wood of the School of Optometry and Vision Science and Institute of Health and Biomedical Innovation at Queensland University of Technology. "The aim of our study was to better understand how these visual conditions affect the ability to recognize and respond to roadside pedestrians at nighttime, and we also wanted to see if certain types of pedestrian clothing could improve the ability of a driver to recognize pedestrians at night, even when the driver had some level of visual loss."

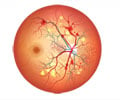

In the study, Even moderate visual impairments degrade drivers' ability to see pedestrians at night, published in the Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science journal, 28 young adult licensed drivers who satisfied the minimum Australian driver's licensing criteria of 20/40 or better vision were used to measure a driver's ability to recognize pedestrians.

The participants drove at night on a closed road circuit wearing simulated refractive blur and cataract lenses. The pedestrians wore one of three different type of clothing: all black; all black with a reflective vest; and all black with reflectors on their wrists, elbows, ankles, knees, shoulders and waist to create a perception of human movement, known as biomotion. Sixteen of the 28 participants were asked to detect the pedestrian against simulated headlight glare.

Findings demonstrated that cataracts are significantly more disruptive than blurred vision. Drivers with simulated blurred vision recognized that a pedestrian was present 52.1% of the time and those with simulated cataracts recognized pedestrians only 29.9% of the time. The research team found that pedestrians wearing the reflective strips to create the biomotion condition were much more visible to drivers (82.3% of the time) than those wearing all black (13.5% of the time). Whether glare was present or not, none of the drivers with simulated cataracts recognized the pedestrian wearing black.

The results also show how these impairments reduce the distances at which drivers first recognize the presence of pedestrians at night. In the experiment, drivers with normal vision recognized pedestrians at longer distances: on average 3.6 times longer than drivers with blurred condition and 5.5 times longer than drivers with cataract conditions.

"Future studies should further explore the impact of uncorrected refractive error, cataracts and other forms of visual impairment on driving performance and safety as well as determine the value of some relatively new ways to measure visual abilities, such as straylight testing and contrast sensitivity," suggests Wood. "It is possible that measuring only visual acuity does not provide us with the best way to determine who is safe to drive."

Source-Eurekalert

MEDINDIA

MEDINDIA

Email

Email