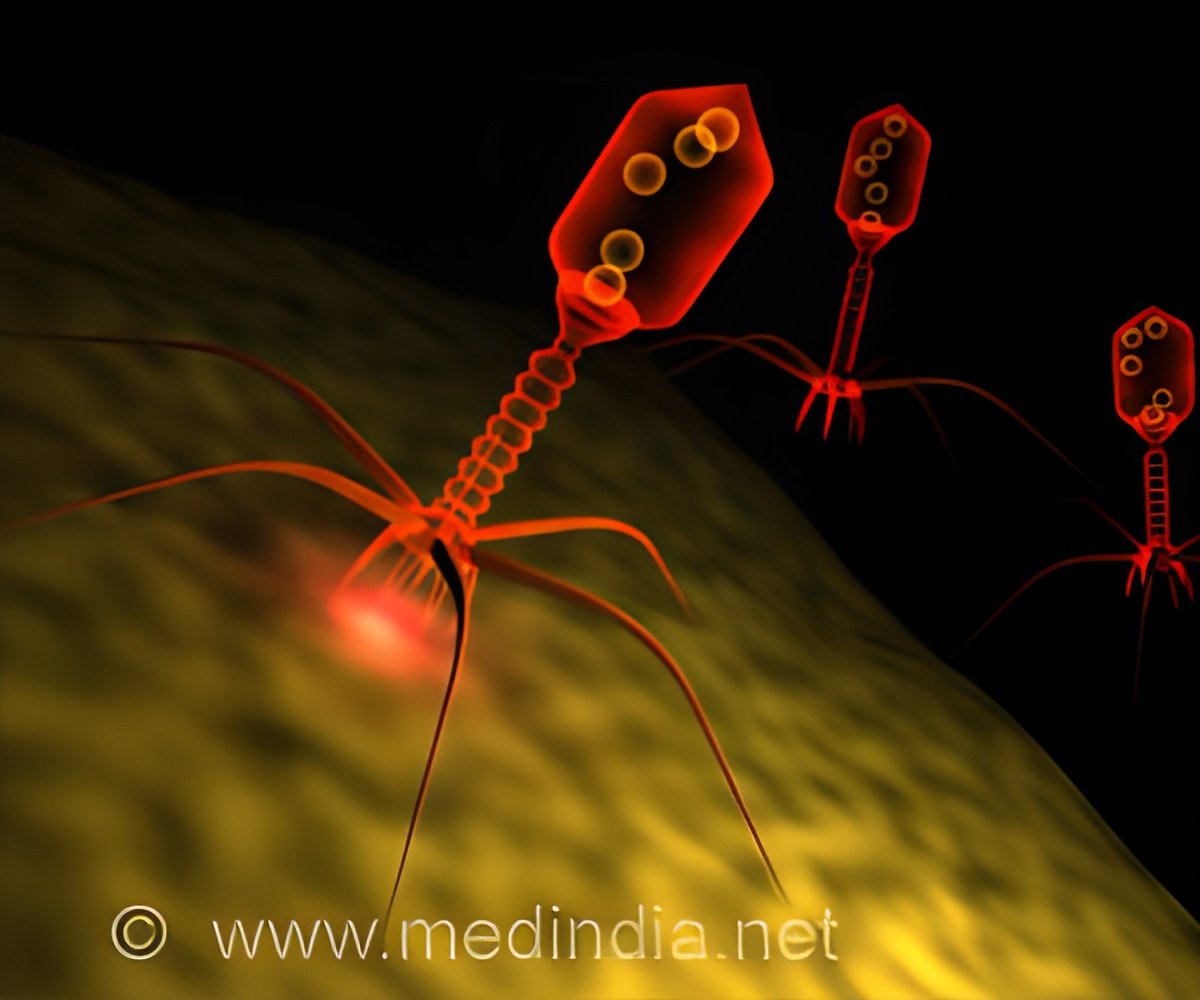

‘Phages have high host specificity, meaning little or no damage to neighbouring good bacteria, and they do not drive the development of resistance in non-target bacterial species.’

"We tend to think of phages as nature's 'nano-machines', self-assembling complex biological survival machines capable of replicating faster than any other biological agent," said Dr. Hill. "They are highly diverse, highly dynamic, and highly specific to their targets, and as antibiotic-resistant 'superbugs' continue to emerge around the world, they may be among our best allies in the future." Despite having been discovered a century ago, their use in clinical therapy continues to encounter several challenges. "One of the challenges lies in the fact that more than 90% of phage populations are as yet unidentified, and therefore considered to be the 'dark matter' of the biological world," said Dr. Hill. "Coupled with manufacturing challenges, regulatory hurdles and the need for clinical validation, the path to pharma may seem long, but researchers are heading in the right direction."

Phages were used for more than 75 years as therapy in Eastern Europe, but they fell out of favour in the western world when antibiotics were discovered. They are now becoming attractive again because of the rise in antibiotic resistance. A unique selling point is their host specificity, meaning little or no collateral damage to neighbouring ('good') bacteria, and they do not drive the development of resistance in non-target bacterial species.

"Whilst regulated phage therapy may take some time, it has been highly successful in recent 'compassionate' cases where patients' lives were on the line," said Dr. Forde. "But for regulated interventions, we need to play the waiting game as more genomic, physiological, pharmacological, and clinical data are gathered. And wait we will."

Advertisement