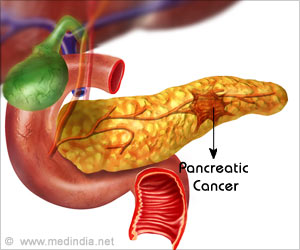

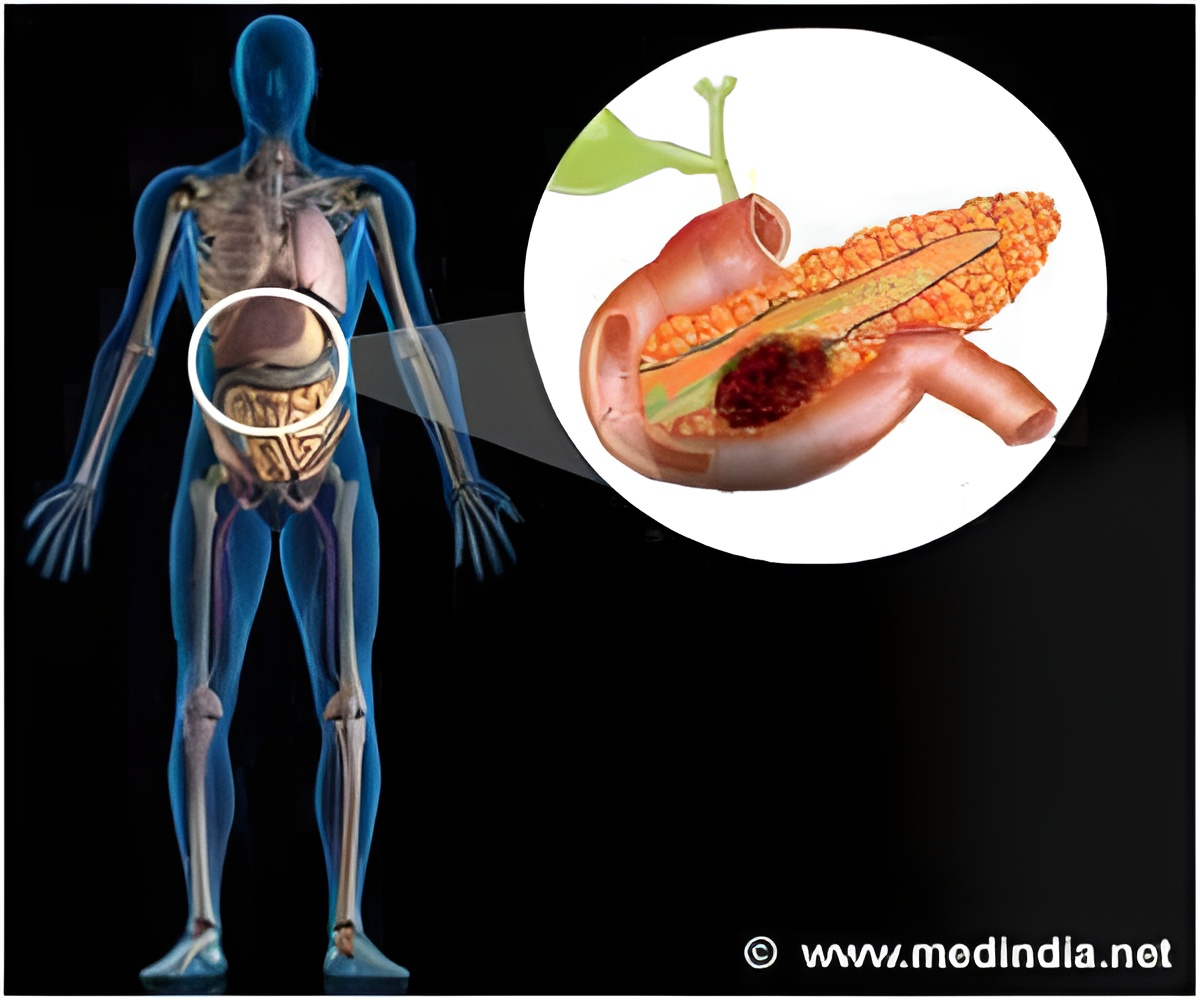

Researchers have found that eliminating desmoplasia, the scar tissue produced by pancreatic cancer, can speed up the growth of tumor.

Several drugs targeting desmoplasia are in clinical trials and one was recently stopped early because of poor results. "Our study explains why this didn't work," Rhim says.

The researchers were able to arrive at this surprising conclusion by using a better mouse model. Previous models have used mice with compromised immune systems injected with human pancreatic cancer cells, producing tumors that don't closely resemble human pancreatic cancer. The current model utilizes mice that are genetically engineered to express the two most common genetic mutations seen in pancreatic cancer. The mice developed cancer spontaneously, and the cancer closely resembled human pancreatic cancer.

Results of the study appear in Cancer Cell. The work represents a collaboration among teams at the University of Pennsylvania, Columbia University, Johns Hopkins University, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and Mayo Clinic.

Using genetically engineered mice, the researchers blocked desmoplasia by knocking down the signaling pathway that produces it. They discovered that desmoplasia prevents the formation of blood vessels that fuel the tumor. When it's suppressed, the blood vessels multiply, giving the cancer cells the fuel to grow. The researchers next wondered: What if you then target blood vessels with treatment?

What they found in this study was that a drug designed to attack blood vessels, called an angiogenesis inhibitor, significantly improved overall survival in the mice who had desmoplasia blocked. Angiogenesis inhibitors already exist on the market with approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Advertisement

This suggests that angiogenesis inhibitors may be effective in patients with undifferentiated tumors.

Advertisement

Source-Eurekalert