University of Copenhagen scientists have succeeded in developing a vaccine, which provides future hope for medical protection from hepatitis C.

"The hepatitis C virus (HCV) has the same infection pathways as HIV," said Jan Pravsgaard Christensen, Associate Professor of Infection Immunology at the University.

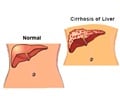

"Approximately one newly infected patient in five has an immune system capable of defeating an acute HCV infection in the first six months. But most cases do not present any symptoms at all and the virus becomes a chronic infection of the liver," he said.

Every year three or four million more people become infected and the most frequent path of infection is needle sharing among drug addicts or tattoo artists with poor hygiene, such as tribal tattoo artists in Africa and Asia.

Fifteen percent of new infections are sexually transmitted, while ten percent come from unscreened blood transfusions.

The new vaccine technology was developed by Peter J. Holst, a former PhD student now a postdoc with the Experimental Virology group, which also includes Professor Allan Randrup Thomsen and Christensen.

"We took a dead common cold virus, an adenovirus that is completely harmless and which many of us have met in childhood," Christensen said.

"The immune defences would then be presented with a larger section of the molecule concerned. You may say that the immune defences were given an entire palm print of the internal genes instead of just a single fingerprint," he said.

This strategy resulted in two discoveries from the team. Firstly, the mice were vaccinated for HCV in a way that meant that protection was independent of variations in the surface molecules of the virus.

Secondly, the immune defences of the mice saw such an extensive section of the internal molecule that even though some aspects of it changed, there were still a couple of impressions the immune defences could recognise and respond to.

The finding has been published in the Journal of Immunology.

Source-ANI

MEDINDIA

MEDINDIA

Email

Email