Don't you think that stem cells are special?

Now, for the first time, researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine have identified how telomerase is recruited to chromosome ends — and figured out a way to block it.

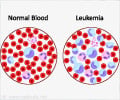

"If telomerase is unable to maintain the ends of the chromosomes, cells will stop multiplying," said professor of medicine Steven Artandi, MD, PhD. "This would be advantageous in cancer cells, but in normal stem cells it can cause severe dysfunction and lead to diseases such as pulmonary fibrosis, aplastic anemia and a genetic condition called dyskeratosis congenita. We want to understand how telomerase works, and to develop therapies for cancer and these other diseases."

Artandi is the senior author of the research, which will be published Aug. 3 in Cell. He is also a member of the Stanford Cancer Institute. Graduate student Franklin Zhong is the first author of the study.

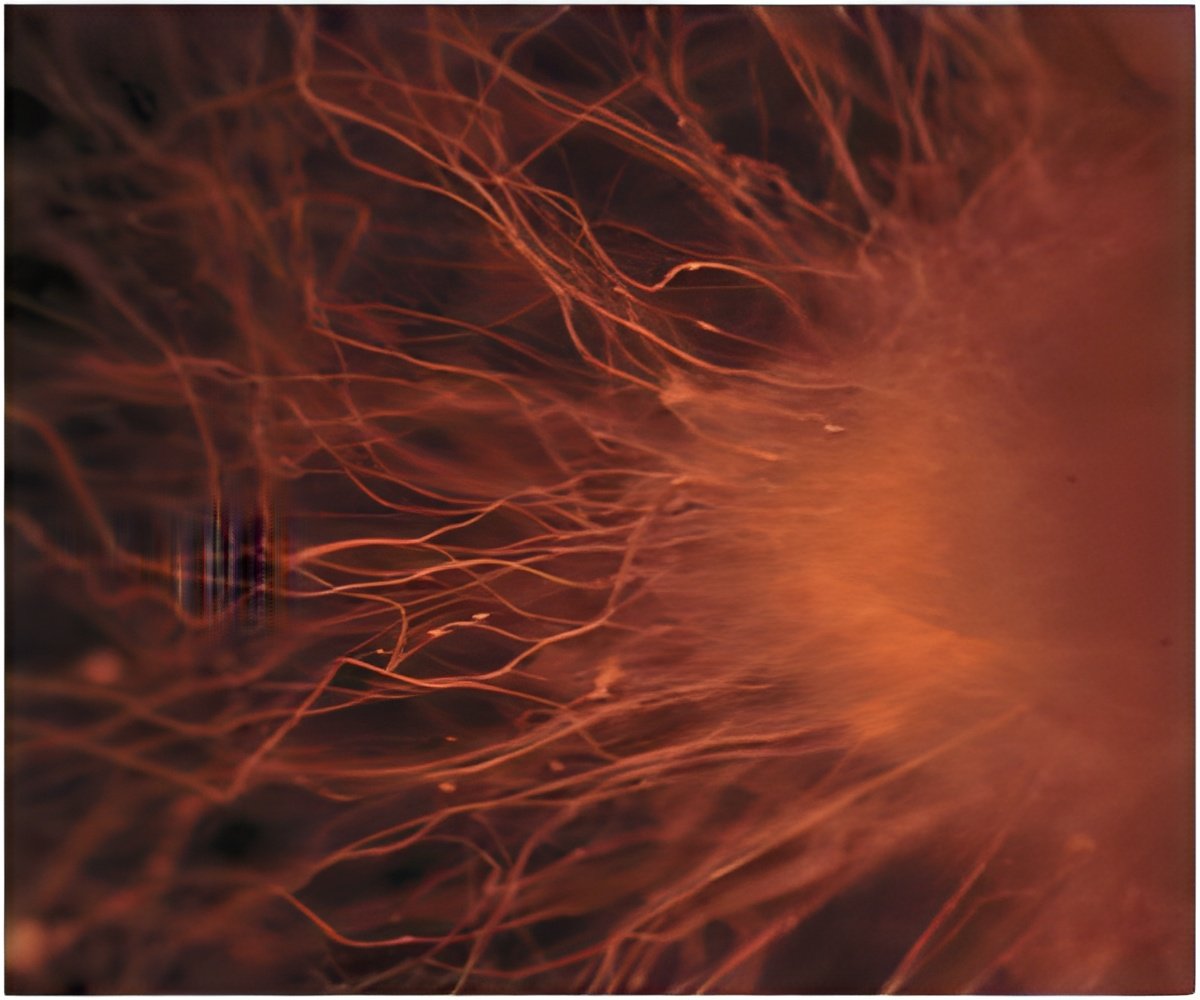

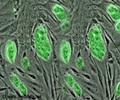

Telomerase is normally expressed in adult stem cells and immune cells, as well as in cells of the developing embryo. In these cells, the enzyme caps off the ends of newly replicated chromosomes, allowing unfettered cell division. Without telomerase, cells stop dividing or die when the ends — called telomeres — fall below a minimum length. Unfortunately, the enzyme is also active in nearly all cancer cells.

Earlier research in Artandi's lab identified a protein called TCAB1 that brings the telomerase complex (actually a large clump of many proteins) to a processing area in the cell's nucleus called a Cajal body. But no one knew how the complex was then ferried to the ends of telomeres, and research was stymied by the complex's large size, multiple components and relative scarcity.

"When we mutated this site in TPP1," said Artandi, "we blocked the interaction between the two proteins and prevented telomerase from going to the telomeres. And when we interfered with this interaction in human cancer cells, the telomeres began to shorten." The researchers are now assessing whether the life span of the cancer cells, and their ability to divide unchecked, will also be affected by the treatment.

"It was impossible to even begin to understand this mechanism before we knew how these two molecules interact," said Artandi. "But now that we're getting a handle on this, we can begin to think about developing inhibitors — maybe in the form of peptides or small molecules — that can mimic this disruption. This could be very valuable in cancer therapies."

Source-Eurekalert

MEDINDIA

MEDINDIA

Email

Email