The three-drug combination - FAK inhibitors, immune therapy and chemotherapy - showed the best outcomes for survival rate in some mice.

TOP INSIGHT

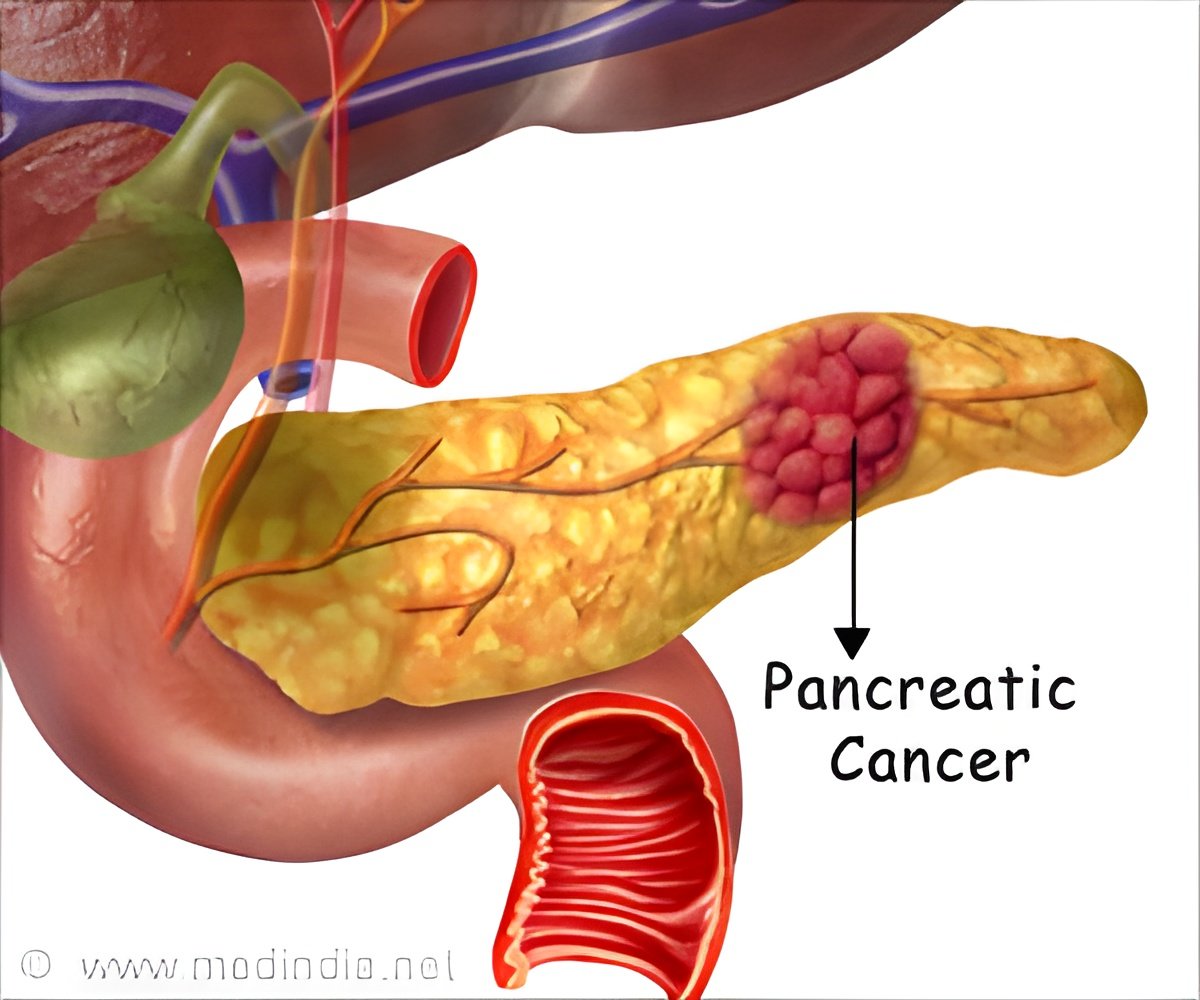

Blocking proteins called focal adhesion kinases which are known to be involved in the formation of fibrous tissue might diminish fibrosis and immunosuppression in pancreatic cancer.

Unlike other cancer types, pancreatic tumors are characterized by a large amount of what DeNardo describes as scar tissue. This extra connective tissue and the cells that deposit it provide a protective environment for cancer cells, stopping the immune system from attacking the tumor cells and limiting the cancer's exposure to chemotherapy delivered through the bloodstream. DeNardo and his colleagues investigated whether some of this protection might be lost if they could disrupt the proteins that help fibrous tissue adhere to itself and surrounding cells.

"Proteins called focal adhesion kinases are known to be involved in the formation of fibrous tissue in many diseases, not just cancer," DeNardo said. "So we hypothesized that blocking this pathway might diminish fibrosis and immunosuppression in pancreatic cancer."

Focal adhesion kinase (FAK) inhibitors have been developed in other areas of cancer research, but DeNardo and his colleagues, including oncologist Andrea Wang-Gillam, MD, PhD, an associate professor of medicine, are the first to test them against pancreatic cancer in conjunction with immunotherapy. In the mouse study, an investigational FAK inhibitor was given in combination with a clinically approved immune therapy that activates the body's T cells and makes tumor cells more vulnerable to attack.

Mice with a model of pancreatic cancer survived no longer than two months when given either a FAK inhibitor or immune therapy alone. Adding FAK inhibitors to standard chemotherapy improved tumor response over chemotherapy alone. But the three-drug combination - FAK inhibitors, immune therapy and chemotherapy - showed the best outcomes in laboratory studies, more than tripling survival times in some mice. Some were still alive without evidence of progressing disease at six months and beyond.

"This trial is one of about a dozen we are conducting specifically for pancreatic cancer at Washington University," she said. "We hope to improve outcomes for these patients, especially since survival with metastatic pancreatic cancer is typically only six months to a year. The advantage of our three-pronged approach is that we are attacking the cancer in multiple ways, breaking up the fibers of the tumor microenvironment so that more immune cells and more of the chemotherapy drug can attack the tumor."

Source-Newswise

MEDINDIA

MEDINDIA

Email

Email