Mice that had been bred at their facility had a greater number of immune cells in the gut than mice purchased from an outside vendor.

TOP INSIGHT

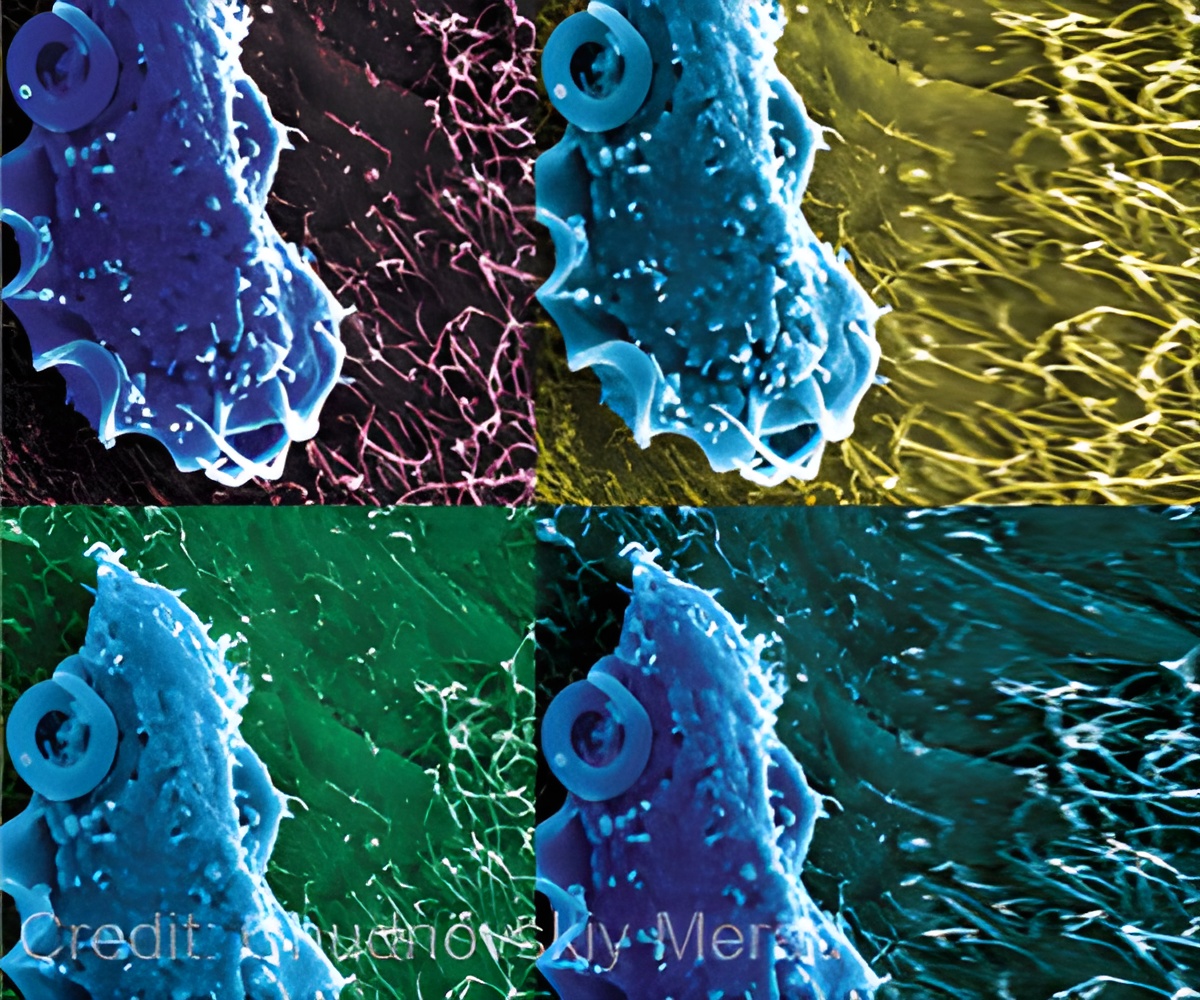

Host-protozoan interactions protect from mucosal infections through activation of the inflammasome in the gut epithelial cells.

Further investigations showed that when this protist was given to the mice that didn't have it, they, too, had an increase in the number of immune cells in their guts and also increased inflammatory cytokines. The researchers set out to discover the underlying mechanism. They found that T. mu activates the inflammasome in the gut epithelial cells of the mice, which in turn led to the activation of cytokines. They also found that dendritic cells were required to induce inflammation.

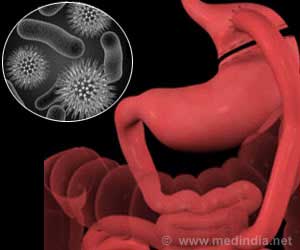

To determine whether colonization of T. mu in the gut affected the mice's ability to fight off infection, they infected mice with Salmonella and found that the animals that had T. mu as part of their microbiome were very resistant to Salmonella infection. "The protective effect of this species is very striking," Chudnovskiy says.

T. mu was found to be an ortholog of Dientamoeba fragilis, a parasite that's found in the guts of many humans, but the researchers don't know if D. fragilis also has a protective effect. It's something they plan to study. "People from industrialized countries traveling to emerging countries are more susceptible to intestinal infection than the indigenous population," Merad explains. "It's possible that protists, which are known to be common in emerging countries, contribute to the protective effect against intestinal pathogenic infections."

She adds: "The fight against pathogens determined the survival of the human species, and those with stronger immune systems are the ones who survived. It is likely that the microbiome is a big part of the evolutionary process. Thus, identifying those commensals that confer immune strength in exposed communities should help identify novel therapeutics."

Source-Eurekalert

MEDINDIA

MEDINDIA

Email

Email