GLUT3 plays the predominant role in platelet activation and mice with reduced GLUT3 in platelets survived pulmonary embolism.

TOP INSIGHT

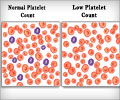

Mice lacking the proteins that platelets use to import glucose from the circulation have lower platelet counts, and their platelets live shorter lives.

The findings, published in Cell Reports and in a related paper published in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology (ATVB), may have implications for understanding the increased risk of thrombosis--blood clots inside blood vessels--in people with diabetes.

The research team found that mice lacking the proteins that platelets use to import glucose from the circulation have lower platelet counts, and their platelets live shorter lives.

"We found that glucose metabolism is very critical across the entire life cycle of platelets--from production, to what they do in the body, to how they get cleared from the body," says E. Dale Abel, MD, PhD, professor and DEO of internal medicine at the UI Carver College of Medicine and director of the Fraternal Order of Eagles Diabetes Research Center at the UI.

Two proteins--glucose transporter (GLUT) 1 and GLUT3--are required for glucose to enter platelets. Abel and his colleagues studied genetically engineered mouse models that were missing GLUT1 and GLUT3 or GLUT3 alone and observed how platelet formation, function, and clearance were affected.

The researchers were able to pinpoint two causes for the low platelet count in mice lacking GLUT1 and GLUT3: fewer platelets being produced, and increased clearance of platelets.

They also tested the megakaryocytes in culture, stimulating them to create new platelets, and found that the generation of new platelets was defective.

"Clearly, we show that there's an obligate need for glucose to bud platelets off from the bone marrow," Abel says.

In addition, the team observed that young platelets functioned normally, even in the absence of glucose. But as they aged, the platelets were cleared from the circulation earlier than normal because they were being destroyed.

"We identified a new mechanism of necrosis by which the absence of glucose leads to the cleavage of a protein called calpain, which marks them for this necrotic pathway," Abel says. "If we treated the animals with a calpain inhibitor, we could reduce the increased platelet clearance."

The team also sought to determine whether platelets could exist and function when mitochondria metabolism is halted. The mice were injected with a mitochondrial poison at a dose that a healthy mouse can tolerate. In the mice deficient in GLUT1 and GLUT3, however, platelet counts dropped to zero within about 30 minutes.

"This work defined a very important role for metabolism in how platelets leave the bone marrow, how they come into circulation, and how they stay in circulation," Abel says. "It could even have implications for why platelets have to be used within a certain period of time when they're donated at the blood bank--the fresher the better."

In the related study in ATVB, the research team showed that GLUT3 played the predominant role in platelet activation and that mice with reduced GLUT3 in platelets survived pulmonary embolism and developed less severe arthritis in a model of rheumatoid arthritis.

Abel says this study sets the stage for exploring strategies in which modifying platelet glucose utilization could be harnessed for therapeutic purposes in conditions in which inhibiting platelet activation might be beneficial.

The work is part of a broader, National Institutes of Health-funded collaboration with researchers at the University of Utah that seeks to understand the mechanisms for increased risk of thrombosis in diabetes.

"We know that in diabetes, platelets are using too much glucose," Abel says. "This increase in glucose metabolism does correlate with the platelet hyperactivity that characterizes many diabetic vascular complications. Reducing the ability of platelets to use glucose could be of therapeutic benefit in the context of diabetes."

Source-Eurekalert

MEDINDIA

MEDINDIA

Email

Email