‘A significant percentage of lymphoma patients undergoing transplants with their own blood stem cells carry acquired genetic mutations that increase their risks of developing second hematologic cancers.’

Tweet it Now

Transplant recipients who were mutation carriers had a higher risk -

14.4% versus 4.4% - of developing a second blood cancer

over the next 10 years compared with those lacking the mutation. The

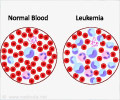

second cancers were acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic

syndrome.Carriers of the mutations were also less likely to survive for 10 years (30.6% versus 60.9%) than individuals lacking the mutations. The greater mortality in mutation carriers wasn't only due to second cancers, but was also the result of other conditions such as heart attacks and strokes, for reasons the scientists say aren't yet clear.

The most commonly mutated gene in the transplant patients was PPM1D, which plays a key role in cells' DNA damage repair toolkit.

The mutations cause an abnormal condition called CHIP (clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential), an age-related phenomenon that occurs in 10 to 15% of patients over age 65. In clonal hematopoiesis, some blood-forming stem cells acquire mutations and spawn clones - subpopulations of identical cells that expand because they have gained a competitive advantage over normal stem cells. Individuals with CHIP don't have symptoms or obvious abnormalities in their blood counts, but researchers are studying whether CHIP in some cases might represent the earliest seeds of blood cancers.

The new study is the first to systematically look at how CHIP influences outcomes in patients undergoing autologous stem cell transplants, according to the report, whose first author is Christopher J. Gibson of Dana-Farber. The senior author is Benjamin L. Ebert of Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women's Cancer Center.

Advertisement

The CHIP mutations may be caused by a combination of aging and prior treatment with chemotherapy for their disease, and could also be related to the lymphoma itself, Gibson said.

Advertisement

Source-Eurekalert