‘Harmful bacteria develop sub-populations that are each pre-adapted to a different environment or task. This pre-adaptation gives them an extra advantage during invasion and in overcoming the immune system.’

Tweet it Now

The recently discovered strategy is the generation

of non-genetic variability, in which bacteria develop sub-populations

that are each pre-adapted to a different environment or task. This

pre-adaptation could give invading bacteria an extra advantage during

invasion and in overcoming the immune system. Called phenotypic

variability, this variation involves the development of sub-populations

of bacteria with altered traits such as size or behavior.

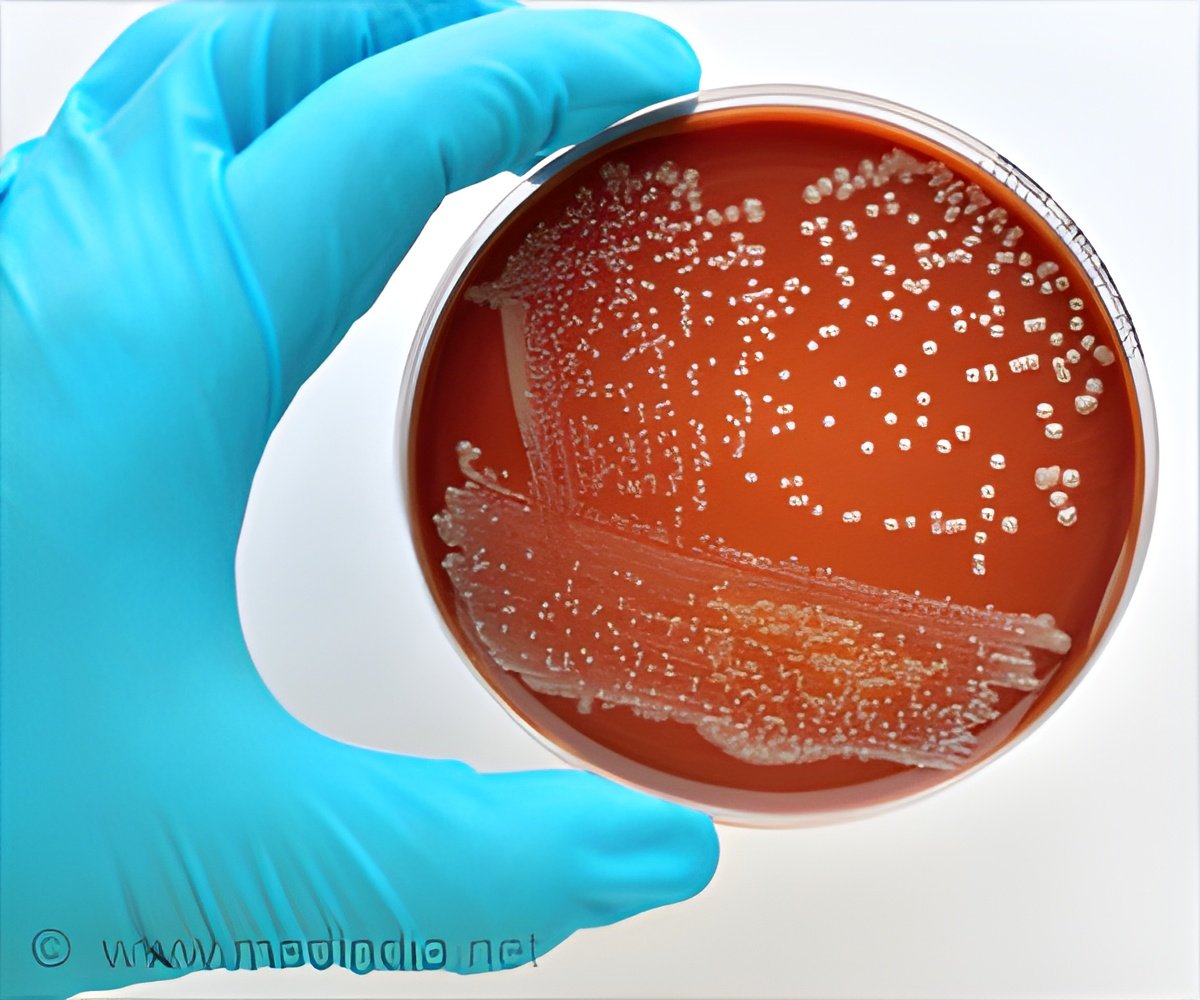

To better understand this survival strategy, researchers Irine Ronin, Naama Katsowitz, Ilan Rosenshine and Nathalie Q. Balaban, led by Dr. Irine Ronin from the Balaban lab at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem's Racah Institute of Physics, examined whether non-genetic variability plays a role in the virulence of a human-specific pathogen, enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), responsible for many infant deaths worldwide.

Their goal was to uncover whether exposing EPEC to challenging conditions similar to the ones they would encounter in a human can trigger EPEC to spontaneously differentiate into different bacterial sub-populations. To do this, they used mathematical modeling and genetic analysis.

Their analysis, reported in the peer-reviewed journal eLife, revealed that EPEC spontaneously differentiates into two sub-populations, one of them particularly virulent, when exposed to conditions that mimic the host environment. Surprisingly, they found that once triggered, this hyper-virulent state maintains a very long memory and remains hyper-virulent for many generations. In addition, they identified the specific regulatory genes that control the switch between the non-virulent and hyper-virulent states in EPEC bacteria.

"These results shed new light on bacterial virulence strategies, revealing the existence of pre-adapted EPEC subpopulations which can remain primed for infection over weeks," said Prof. Nathalie Q. Balaban. "They also show that long-term memory drives the expression of the pathogen's major virulence factors, even upon shifting to conditions that do not favor their expression."

Advertisement

Source-Eurekalert