Bone marrow transplantation has long been a powerful therapy in combating cancer and other disorders, but it also involves serious risks that make physicians wary. Patients getting bone marrow transplants must first be given powerful drugs or radiation treatments that wipe out their own bone marrow and immune cells, leaving them vulnerable to life-threatening infections.

The patient's supply of blood and immune stem cells is then replenished by bone marrow from a donor, but this bone marrow also contains mature immune cells called T cells that can see the patient's tissues as immunologically foreign. T cells that react against patient tissues cause a disorder called graft versus host disease, or GVHD, which can severely damage the patient's body.

Conventional wisdom among transplantation specialists has been that the bone marrow transplant should contain some T cells from the donor. Although the presence of mature donor T cells is known to cause GVHD, it is generally believed that these T cells can help protect the patient from infectious disease and fight cancer until the transplanted stem cells can mature into a new immune system. It is also thought that the presence of mature T cells decreases the chance that the patient will reject the graft.

"People think that T cells are a necessary evil because they help with engraftment and immune reconstitution," Shizuru said. For these reasons, patients are not given pure blood-forming stem cells as part of current therapy.

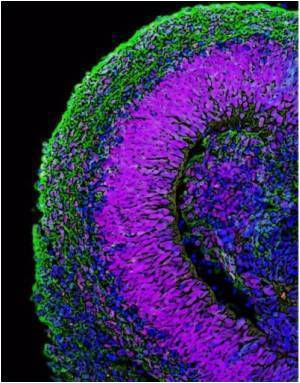

The new research by Shizuru, lead author, and research associate Antonia Mueller, MD, and their colleagues calls into question those assumptions. When they compared mice given pure stem cells with mice given a mixture of stem cells and mature T cells, they found that the mice given pure stem cells were better at forming new blood cells and faster in regenerating lymphoid tissues. T cells from the donor seemed to work against the grafted stem cells and inhibit their maturation into mature immune cells. Furthermore, Shizuru said follow-up studies showed that the donor's T cells did not help eradicate pathogens.

Advertisement

In the new study, Shizuru and her colleagues took a more precise look at the action of the mature T cells by comparing how well both groups of mice were able to regenerate bone marrow, blood and lymphoid tissues in the early post-transplant period (within one week) up through one year after transplantation.

Advertisement

Source-Eurekalert