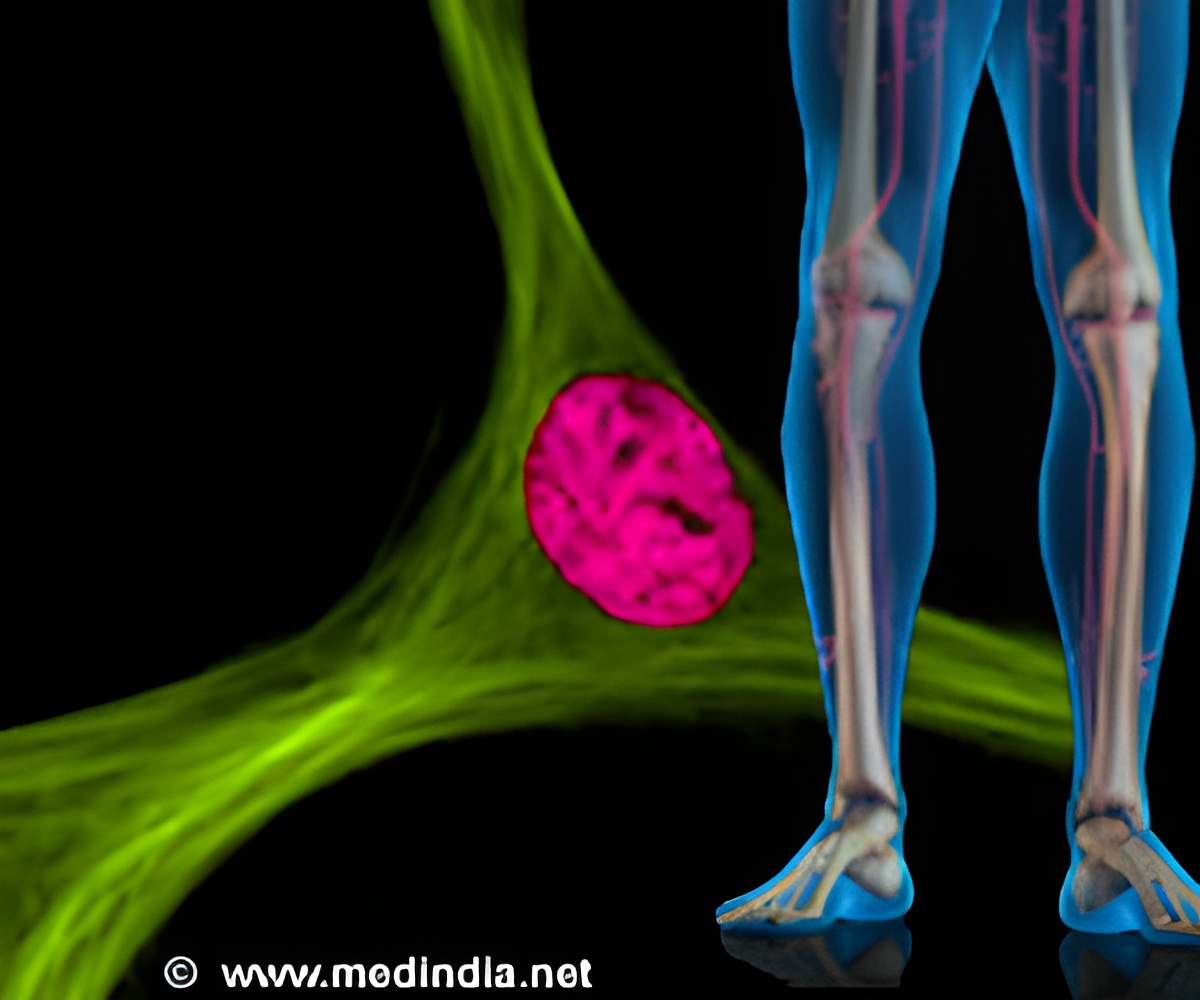

‘Researchers triggered the transport of a protein called actin into the nuclei of cells to alter mesenchymal stem cells to become bone cells.’

Tweet it Now

"And the bone forms quickly," said Dr Janet Rubin, senior author of the paper and professor of medicine at the UNC School of Medicine. "The data and images are so clear; you don't have to be a bone biologist to see what cytochalasin D does in one week in a mouse." Rubin added, "This was not what we expected. This was not what we were trying to do in the lab. But what we've found could become an amazing way to jump-start local bone formation. However, this will not address osteoporosis, which involves bone loss throughout the skeleton."

At the center of the discovery is a protein called actin, which forms fibers that span the cytoplasm of cells to create the cell's cytoskeleton. Osteoblasts have more cytoskeleton than do adipocytes (fat cells). Dr Buer Sen, first author of the Stem Cells paper and research associate in Rubin's lab, used cytochalasin D to break up the actin cytoskeleton. In theory - and according to the literature - this should have destroyed the cell's ability to become bone cells. The cells, in turn, should have been more likely to turn into adipocytes. Instead, Sen found that actin was trafficked into the nuclei of the stem cells, where it had the surprising effect of inducing the cells to become osteoblasts.

"My first reaction was, 'No way, Buer,'" Rubin said. "'This must be wrong. It goes against everything in the literature.' But he said, 'I've rerun the experiments. This is what happens.'" Rubin's team expanded the experiments while exploring the role of actin. They found that when actin enters and stays in the nucleus, it enhances gene expression in a way that causes the cell to become an osteoblast.

"Amazingly, we found that the actin forms an architecture inside the nucleus and turns on the bone-making genetic program," Rubin said. "If we destroy the cytoskeleton but do not allow the actin to enter the nucleus, the little bits of actin just sit in the cytoplasm, and the stem cells do not become bone cells."

Advertisement

Bone formation in mice isn't very different from that in humans, so this research might be translatable. And while cytochalasin D might not be the actual agent scientists use to trigger bone formation in the clinic, Rubin's study shows that triggering actin transport into the nuclei of cells may be a good way to force mesenchymal stem cells to become bone cells.

Advertisement