The clinical efficacy of checkpoint blockade might be dramatically improved if combined with an investigational intervention.

"Many patients have benefited from cancer immunotherapies," says Dmitriy Zamarin, a member of Ludwig's Collaborative Laboratory at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) and lead author of the study together with James Allison of the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, and Jedd Wolchok, Director of the Ludwig Collaborative Laboratory at MSK. "But they have not been effective for all patients, or against all cancer types, since most cancers can potently suppress immune responses. We want to extend the benefits of immunotherapies to more patients and optimize their use against a larger variety of cancers."

Zamarin and his colleagues found that an inflammatory immune response induced in the tumor by NDV primarily accounts for the efficacy of the therapy. The checkpoint blockade antibody used in this study binds CTLA-4, a molecule found on immune cells that acts like a brake (or "checkpoint") on the immune response. A version of this antibody is already used for cancer therapy, and it has proved potent in a clinical trial evaluating its combination with another immunotherapy as well.

The researchers noticed that when NDV was injected into a tumor implanted in mice, cancer-killing immune cells flooded into that tumor. "But we also found, to our surprise, that a similar infiltration of activated immune cells occurred in a distant tumor, one in which the virus was never detected," says Zamarin.

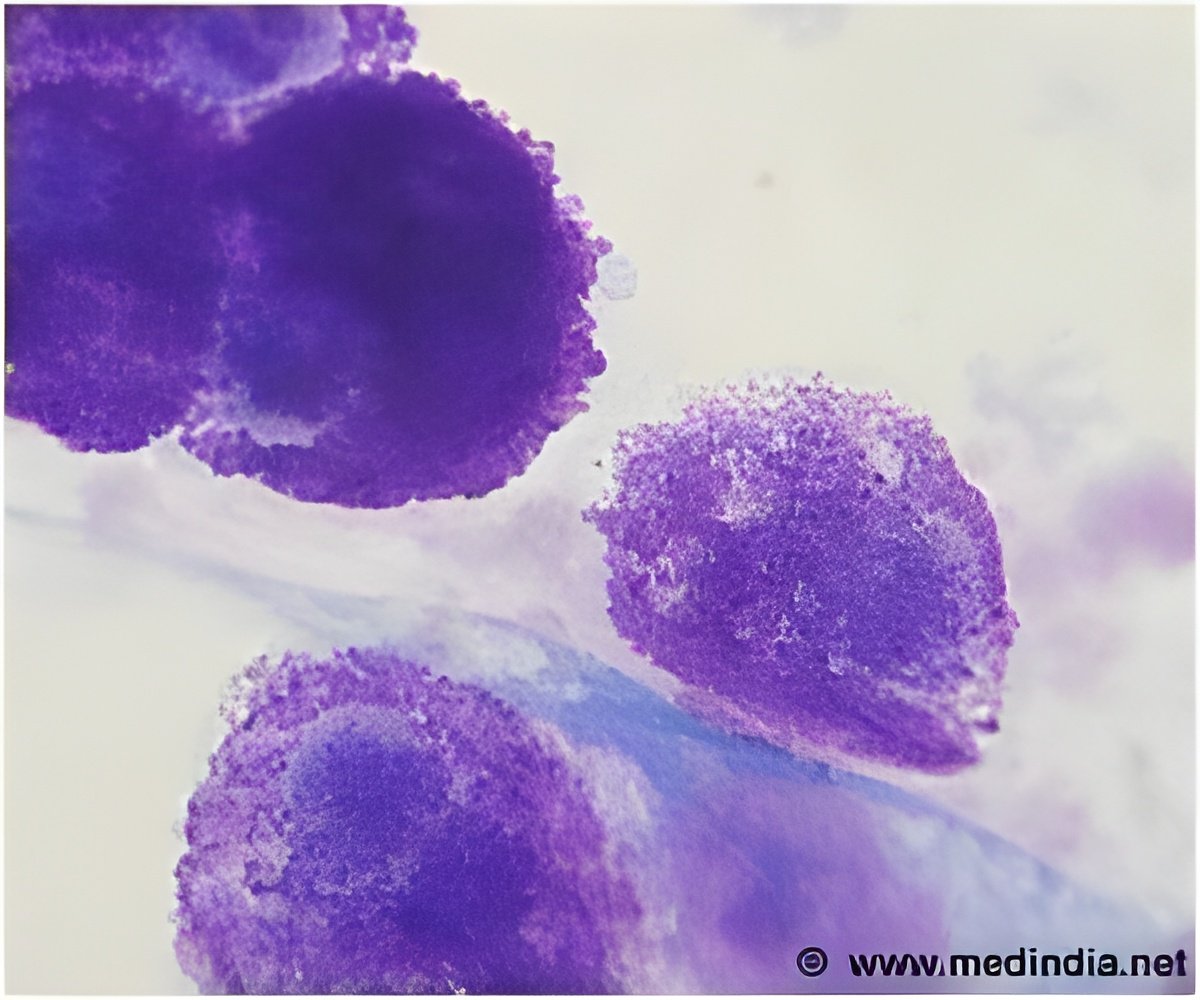

The researchers show that NDV infection alerts T cells of the immune system to the presence of cancer cells, which otherwise suppress immune surveillance and attack. Subsequent injection of the anti-CTLA-4 antibody dials up the incipient anti-tumor response so dramatically that it overcomes the tumor's immune suppression and destroys both NDV-exposed tumors and unexposed tumors. And the effect appears to be durable. When the same tumors are reintroduced into treated animals, they are swiftly eliminated.

Combining the two therapeutic strategies, Zamarin explains, overcomes the limitations of each. Oncolytic virotherapy has long been hindered by the immune system's tendency to disable systemically introduced viruses long before they can target tumors. The current study circumvented this problem by injecting NDV directly into the tumor.

Advertisement

The team also found that NDV could be used to boost the effects of an investigational immunotherapy known as adoptive T cell transfer, in which T cells are taken from patients, trained to recognize specific tumors and then reintroduced into their bodies. Adoptive transfer too has been hampered by the ability of tumors to suppress immune responses.

Advertisement

Source-Eurekalert