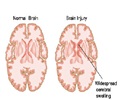

‘Scientists have successfully helped 'jump-start' a man's brain after a coma using incredibly low-energy ultrasound pulses that targeted the thalamus that is the brain's 'sensory hub' controlling waking up, alertness and arousal.’

Tweet it Now

But the region of the brain they targeted with the ultrasound — the thalamus — has previously been shown to be important in restoring consciousness. In 2007, a 38-year-old man who had been minimally conscious for six years regained some functions after electrodes were implanted in his brain to stimulate the thalamus.The UCLA procedure used an experimental device, about the size of a teacup saucer, to focus ultrasonic waves on the thalamus, two walnut-sized bulbs in the center of the brain that serve as a critical hub for information flow and help regulate consciousness and sleep.

The ultrasound device used in the UCLA case was developed by Dr. Alexander Bystritsky, a professor of psychiatry at UCLA who directs the school’s anxiety disorders program. He developed it as a potential treatment for anxiety and other brain disorders, such as seizures, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, and also as a research tool to probe the workings of the healthy brain.

Bystritsky has founded a privately held startup called Brainsonix in order to further develop the device and bring it to market. He donated the use of the device, but because of his role as manufacturer of the device, he was not allowed by UCLA to actively take part in the study.

“We found a way to jump start these circuits back into service,” said the study’s lead author, Martin M. Monti, a UCLA psychologist and neuroscientist who studies cognition and consciousness. The study was published online in the Journal of Brain Stimulation.

Advertisement

Crehan had part of his skull removed to relieve pressure and was placed in a medically induced coma to allow his brain to heal. Doctors attempted to wake him after about a week, said his father, Michael Crehan, but it didn’t go well, so he was returned to the coma for another week. When he was brought out of that coma, he still wasn’t very responsive: He could reach for objects, make small spontaneous movements, and open and close his eyes as if sleeping and waking, but showed little comprehension and no ability to communicate.

Advertisement

“He even gave me a fist bump when I was leaving,” Monti said. “He had emerged.”

Crehan’s recovery was swift and smooth. He left the hospital in four months, faster than anyone expected. He has finished physical and occupational therapy and is now working to strengthen his memory. He is driving, hitting the gym, applying for jobs, and hoping to enter the job market soon.

Monti cautions that the reason for Crehan’s recovery is unclear.

“We could have been very, very lucky that we did our procedure just as he was spontaneously recovering,” Monti said. “It could be he would have recovered anyway, and our stimulation did nothing.”

Research into “disorders of consciousness” has been halting, for several reasons — starting with a lack of understanding of the workings of basic humanconsciousness.

Doctors have also been frustrated by the unpredictability of brain injuries; one severely injured patient might spontaneously emerge from a coma relatively intact, while others linger in vegetative states for years and sometimes decades. Still others remain in a minimally conscious state; they show some awareness and may be able to smile, cry, and even give yes or no responses, but cannot function on their own.

Further complicating matters: Determining a person’s level of awareness can be challenging because episodes of consciousness can be fleeting.

Large-scale trials have been conducted on two medications thought to help recovery. One is the sleeping aid Zolpidem, which sells under the brand name Ambien — and paradoxically, has been shown to ramp up brain activity in some vegetative patients.

Another drug that affects dopamine levels, Amantadine, was shown to speed recovery in a trial of 184 patients with impaired consciousness.

Researchers say it’s been difficult to get funding to study more ambitious treatments, such as implanting electrodes to stimulate the brain. It is also critical, they say, to include patients who have been minimally conscious or vegetative for years and are less likely to spontaneously recover. Crehan was treated just 19 days after his injury.

Cornell neuroscientist Schiff and his colleagues last month published a report of a second patient to receive thalamic brain stimulation via an implanted electrode: a 44-year-old male who had been minimally conscious for 21 years following a traumatic brain injury. This patient did not show the behavioral improvements that Schiff’s first patient did, but the scientists were able to detect systematic changes in the sleep and wake cycle, showing the patient’s brain did respond to the treatment despite the severity and length of his injury, Schiff said.

But that’s just a case study, not a full-scale clinical trial. Schiff estimated that a large study of his technique would cost $10 million to $12 million. “Honestly, when we went to the federal agencies, people didn’t want to pay for it,” he said.

Some of the ambivalence, he said, may stem from the fact that even when treatments restore some consciousness, patients may still be left severely impaired and bedridden. By some estimates, more than 100,000 patients in the United States alone are trapped in states of minimal consciousness; these patients are often viewed as all but dead, their families urged to withdraw life support and donate their organs.

Schiff and Monti, however, argue that restoring even some consciousness can lead to a huge improvement of quality of life for patients, their families, and their caregivers.

Source-Medindia