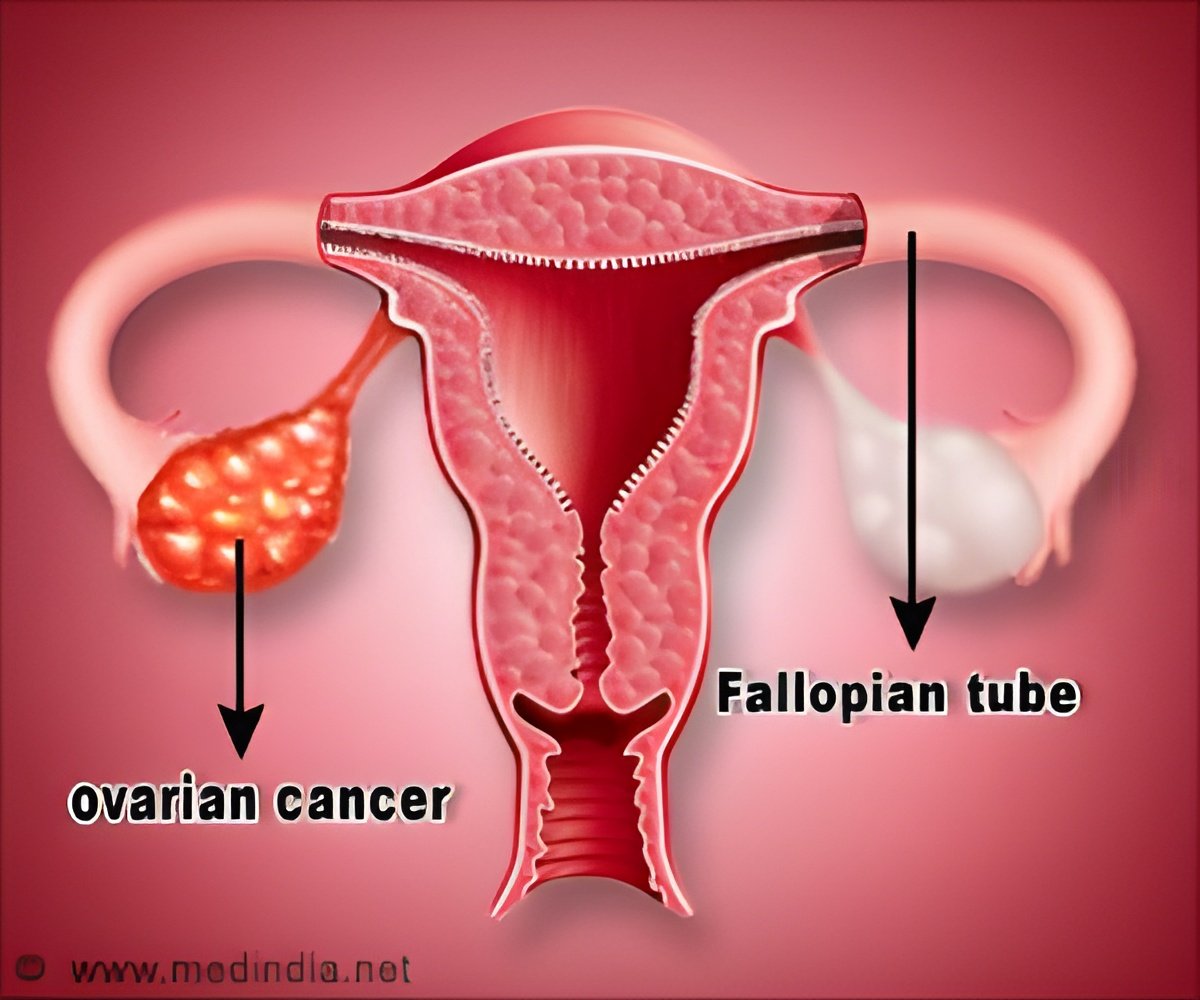

‘Patients with ovarian cancer without BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations could benefit from using the combination of Cediranib with olaparib as they have additive effect in blocking DNA repair.’

Read More..Tweet it Now

DNA repair occurs in several different ways, which is why inhibitors of these specific techniques could be so valuable, Glazer said. "People are recognizing that manipulating DNA repair could be very advantageous to boosting the benefit of traditional cancer treatment." Read More..

"The use of cediranib to help stop cancer cells from repairing damage to their DNA could potentially be useful in a number of cancers that rely on the pathway the drug targets," said the study's lead investigator, Alanna Kaplan, a member of Glazer's team. "If we could identify the cancers that depend on this pathway, we may be able to target a number of tumors."

Cediranib was developed to inhibit vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptors that stimulate the formation of blood vessels that tumors need to grow. But it has offered less benefit than the U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved VEGF pathway inhibitor, Avastin.

However, a recent clinical trial found the combination of cediranib and olaparib (registered as Lynparza) is beneficial in a specific form of ovarian cancer.

Olaparib the first approved DNA repair drug, is known to inhibit a DNA repair enzyme called PARP and has shown promise killing cancer cells with defects in DNA repair due to mutations in the DNA repair genes BRCA1 and BRCA2.

Advertisement

Glazer and his team wanted to understand how cediranib exerted such a powerful effect.

Advertisement

Two decades ago, Glazer demonstrated that, among other things, low oxygen seemed to negatively affect DNA repair. In short, the researchers believed hypoxia caused by cediranib led to weak DNA repair.

But what the new study found is that while cediranib does help stop growth of new blood vessels in tumors, it has a second -- and potentially more powerful -- function. It switches off DNA repair at an early stage in the DNA repair pathway. "Unlike olaparib, it doesn't directly block a DNA repair molecule, stopping DNA from stitching itself back together. It affects the regulation by which DNA repair genes are expressed," said Glazer.

Cediranib makes tumors more sensitive to the effects of olaparib because it stops cancer cells from repairing their DNA by a mechanism called homology-directed repair (HDR). This occurs when a healthy strand of DNA is used as a template to repair the identical, but damaged, DNA strand, he added.

Cediranib's direct effect comes from inhibiting the platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), which is involved in cell growth. The drug, therefore, works to inhibit both angiogenesis and the ability of tumors to grow by repairing mishaps in their DNA. "The capacity of the drug to harm blood vessel formation was not a surprise. But its direct effect on DNA repair through the PDGF receptor was completely unexpected," Glazer said.

"The goal now is to investigate how we can broaden the potential of this synthetic lethality to other cancer types," he said.

Source-Eurekalert