Indiscriminate and unchecked consumption of alcohol is an abusive and irresponsible act, leading to a significant number of untimely deaths all over the world.

Sadly, despite the fact that people being generally aware of the damaging effects of alcohol – it continues to be an important cause of serious health problems and in some instances, even “alcohol related deaths”.Alcohol causes approximately 1.8 million deaths a year and it is the third most common cause of deaths in developed countries. Unintentional injuries account for about one third of the deaths from alcohol. In some of the developing countries, where overall mortality is low, alcohol is the leading cause of disease and illness.

Some of the incontrovertible ways in which individuals lose their lives from excessive and abusive drinking of alcohol are homicides, chronic alcohol addiction, suicides, fatal alcohol withdrawal symptoms, alcohol poisoning, traffic deaths, and from diverse alcohol-related birth defects like fetal alcohol syndrome.

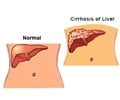

This particular problem in the United Kingdom is undoubtedly huge. The Netherlands, Australia, Norway, Sweden, and New Zealand have similar drinking cultures and genetic backgrounds as United Kingdom, and in the year 1986 they had broadly similar number of death rates because of liver diseases. According to a recent survey by WHO, the liver death rates range from 2.6 per 100 000 in New Zealand to 5.3 in Sweden. In the UK liver death rates doubled from 4.9 to 11.4 since 1986.

Using the Office of National Statistics for alcohol related liver deaths in 2008 as the baseline, it is predicted that by the year 2019 if the green scenario reaches its target of 2500 deaths each year then there would be 22 000 fewer liver deaths in total. Over the coming 20 years, the difference between other scenarios would be 77 000 liver deaths (80% under age 65 years).

There is an extremely strong evidence base for evidence alcohol policy. The most esteemed expert bodies such as WHO, UK's House of Commons Health Committee, and the UK's Academy of Medical Sciences have confirmed that effective alcohol polices have three major components to look for: price, place of sale (availability), and promotions. Now the marketing industry has added one more - product. These four “Ps” constitute the basic components of all marketing activity. On the contrary, the “drinks industry” tends to deny that these “4Ps” apply to alcohol. Instead they try to promote policies based on information, education, and deregulation

A “green scenario” would see a steep decline in UK death rates with the same gradient as that for France - the country with the highest rate of reductions in mortality. The intermediate scenarios would see liver deaths reduction along the gradients followed by the rates in Italy or in the European Union as a whole.

In France, the progressive reduction in liver mortality was achieved without significant increases in alcohol taxation because other factors prevailed. France in the 1960s had high liver death rates because of the excessive consumption of cheap wine. Changing fashion and urbanization led to an initial decline in consumption which accelerated as the connecting links between alcohol and cirrhosis became generally accepted in the late 1960s. The trend was then reinforced by government policies, which incorporated strict regulation of alcohol marketing. The new policies suggest that the government adheres to drinks industry and lacks clear aspiration to diminish the impact of readily available, cheap, and marketed alcohol on individuals and to the society.

Irrespective of the measures that the UK Government chooses to implement their public health strategy, the key test must be the impact on hard outcomes. A change of emphasis has been seen from setting targets for process measures to outcomes measures. Alongside, debates on the effectiveness of individual measures and an outcome framework should be created which establishes the level of liver mortality that the UK aspires to achieve in coming years.

The alcohol scenario in developing countries is perhaps even far worse. The stats are seldom available and policymakers have no time to look for solutions as they seem to be grappling all the time with basic health issues. Health has low priority as far as government spending is concerned in these countries

Reference

http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(11)60022-6/fulltext

Source-Medindia