Highlights

- After an infection, a small population of the microbes continue to thrive in the immune cells of the host, even after the symptoms subside.

- The immune cells that house the microbes are responsible for killing pathogens and also activating a more robust immune response.

- This prepares the immune system for any new encounters with the pathogen.

An ongoing infection constantly reminds the immune system what the organism looks like and keeps the immune system on alert against new encounters, even while it carries the risk of causing disease later in life, the researchers found.

This understanding could help researchers design vaccines and treatments for persistent pathogens.

What Persistent Infection Does

"People had been thinking of the role of the immune system in persistent infection in terms of mowing down any pathogens that reactivate in order to protect the body from disease," said Stephen Beverley, PhD, the Marvin A. Brennecke Professor of Molecular Microbiology and the study's senior author.

A small population of microbes remains in the body in persistent infections, long after the patient's symptoms are gone.

"A lot of pathogens cause persistent infections, but the process was something of a black box," said Michael Mandell, PhD, the first author on the study. Mandell, who conducted the research for the study as a graduate student, is now an assistant professor at the University of New Mexico. "Nobody really knew what was going on during persistent infection and why it was associated with immunity."

Study

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis studied leishmaniasis, to explain the seemingly paradoxical connection between long-term infection and long-term immunity.

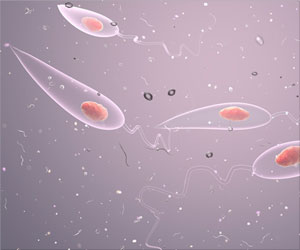

Leishmaniasis is caused by leishmania, a group of parasites that cause ulcers on the skin and can infect internal organs. It can lead to disfigurement and kills an estimated 250 million people every year. Approximately 12 million people have active disease.

Once a person is infected, he or she is protected from getting sick a second time. In other words, infection confers long-term immunity.

This is because, people continue to harbor the parasite at low numbers for years after they recover from the disease, which benefits them.

Studies in mice have shown that completely clearing the parasite often makes the animals susceptible to another bout of disease if they encounter the parasite again.

The researchers used fluorescent markers to distinguish different types of mouse cells, and found that most of the parasites harbor in immune cells that are capable of killing the parasites.

The parasites appeared normal in shape and size and continued to multiply, yet the total number of parasites stayed the same over time and did not increase.

How the Immune System Works

"Mike Mandell called it the 'Jimmy Hoffa effect' because we couldn't locate the body," Beverley said. "We were unable to show directly that the parasites were being killed. But some of them must have been dying because the numbers weren't going up."

The immune cells that houses the parasites are responsible for killing pathogens and activating a more robust immune response.

This process of the ongoing multiplication and killing of parasites explains the long-term immunity associated with persistent infection, and thus explains why people typically can't get sick with the same pathogen twice.

"It seems that our immunologic memory needs reminding sometimes," Mandell said. "As the persistent parasites replicate and get killed, they are continually stimulating the immune system, keeping it primed and ready for any new encounters with the parasite."

The research is published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Reference

- Stephen Beverley et al. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences; (2017)

Source-Medindia