Jan 2006, India: A 7-day old baby was charred to death due to a short circuit in a neonatal unit in Niloufer Hospital, robbing parents of their joy and hopes. The incubator in which the baby was kept caught fire. The parents blamed the doctors stating that the incident had happened due to negligence of the hospital staff while the health workers argued that four other babies in the unit were saved due to prompt action of the medical staff who switched off the power supply. The poor mother’s cry is lost in a country with a population of over a billion where the death of one single baby girl would mean nothing at all. But I bet the poor mother would dare to become pregnant again.

July 2005, India: Ultaf Bi, a resident of Savali village in Karnataka presents to a primary healthcare centre in her village, with complaints of stomach ache. She was ordered to receive an injection in addition to some tablets. While administering the injection, the needle broke and she was asked to visit a private hospital for further treatment. Although a small part of the needle that remained in her arm was removed, she now suffers form paralysis due to nerve damage.

January 2006, India: An emaciated old man lies confined to a dilapidated charpoy at Lok Biradari Prakalp, set up by two doctors who were determined to devote their lives to help a tribal community which has seen nothing but poverty, malnutrition and disease. The patient’s faint but strange wailing is sufficient enough to stir the soul of any person with a compassion to his fellow human beings. Despite the best effort of the doctors, the old man receives only 2 bottles of saline, while actually he needs eight. The next day morning, the faithful wife can be seen holding on to the mortal remains of her husband.

February 2006, India: A man as about the same age as the one mentioned above is admitted to an urban hospital in Delhi for complaints of low grade fever. Routine medical tests are ordered. Within no time a nurse pushes an intravenous cannula gently over the vein for antibiotic administration. Extreme caution is being taken to maintain the prefect temperature in the patient’s room, including the bathroom. Everything happens at the touch of a button, whether it is about adjusting the bed or drawing up a hydraulic food tray beneath the bed or calling the nurse for help. The room has everything from television to plug points to recharge a mobile. Within few days of successful treatment, the patient is discharged from the hospital, led to believe that illness and death happens only to those outside the heaven.

The above-mentioned scenarios only reflect the reality and the lack of the Indian health care system. This indeed in the reach of the health care industry in India, with the rich being offered luxurious medical treatment while the poor and the needy left to the mercy of the state and central governments, national health programmes, NGOs, and health missionaries of course!

Although we have achieved a lot in the health sector since Independence, such as increase in life expectancy, reduction in the infant mortality rate by as much as 50% (68/1000 compared to 146/1000 in 1947), successful provision of immunizations to 42% of children, a rapid growth of the private heath care infrastructure. Infact, more than 50% of the investment in the health care sector is contributed by private sector undertaking.

Although we now have to large extent eliminated the social stigma associated with leprosy, 60% of the world’s leprosy patients are from India. Communicable diseases continue to be responsible for a large proportion of the deaths (42%). Although the Indian Government has been working for the past several decades to improve the situation, diseases like tuberculosis, AIDS, sexually transmitted infections, respiratory infections tropical diseases like malaria continue to haunt the country, claiming a massive number of lives, every year.

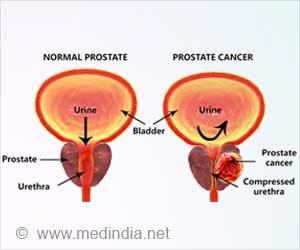

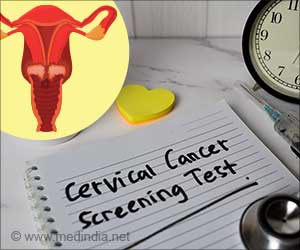

These major public health threats are joined by diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and hypertension, posing a significant challenge to the Indian economy. Cancer, cardiovascular diseases and diabetes have been responsible for 653000, 2820000 and 102000 mortalities respectively were reported in the year 1998.

This being one end of the health care spectrum, millions of people living in the rural areas still do not have access to the most basic health care facilities. A lot of people live in poor, dispossessed conditions so bad that they are unable to afford the bus fares. It is not uncommon sight to see a villager or tribal walk miles to visit a nearby government district hospital, only to see witness the non-availability of the duty doctor.

Although some argue that poverty prevents the realization of health care objectives in this country, the irony is that a number of people in the rural areas are struggling to cope up with their huge medical debts. The excruciating pain associated with high medical costs is even felt in the so-called middle class.

It is alarming to know that with millions living below the poverty line, India spends much less on its health care industry than any other country in the world, even less than that spent by Sri Lanka. The Indian Government spends as little as 0.6 to 0.8 % of the total health care expense. Thanks to the 2006 budget, which has raised the health care spending from 0.9 to 2-3 % of the gross domestic product (GDP).

Several questions arise at this juncture as to whether it is the responsibility of the government to take care of health care, targeted at provision of quality health care at an affordable cost or it is the duty of NGOs to take over? If yes, what then is the role of the government hospitals and public health centres that are supposed to provide medical services to the poor and underprivileged?

Such a complex problem cannot be solved through simple answers but through sustained and co-coordinated efforts of committed health care workers, governments, non-governmental organizations and other leaders. The solution should be worked out at the regional, national and international levels. Most importantly, more than a critical health care design plan it is the implementation that can promise results in the years to come. It is high time that we as Indians orient ourselves to outcomes rather than blame the government for low budgetary allocation or ineffective implementation of health care programmes. The take home message then? Together, we can make a difference!