‘After the implantation of a prosthetic device the brain undergoes plastic changes to re-learn how to make use of the new artificial and probably aberrant visual signals.’

Tweet it Now

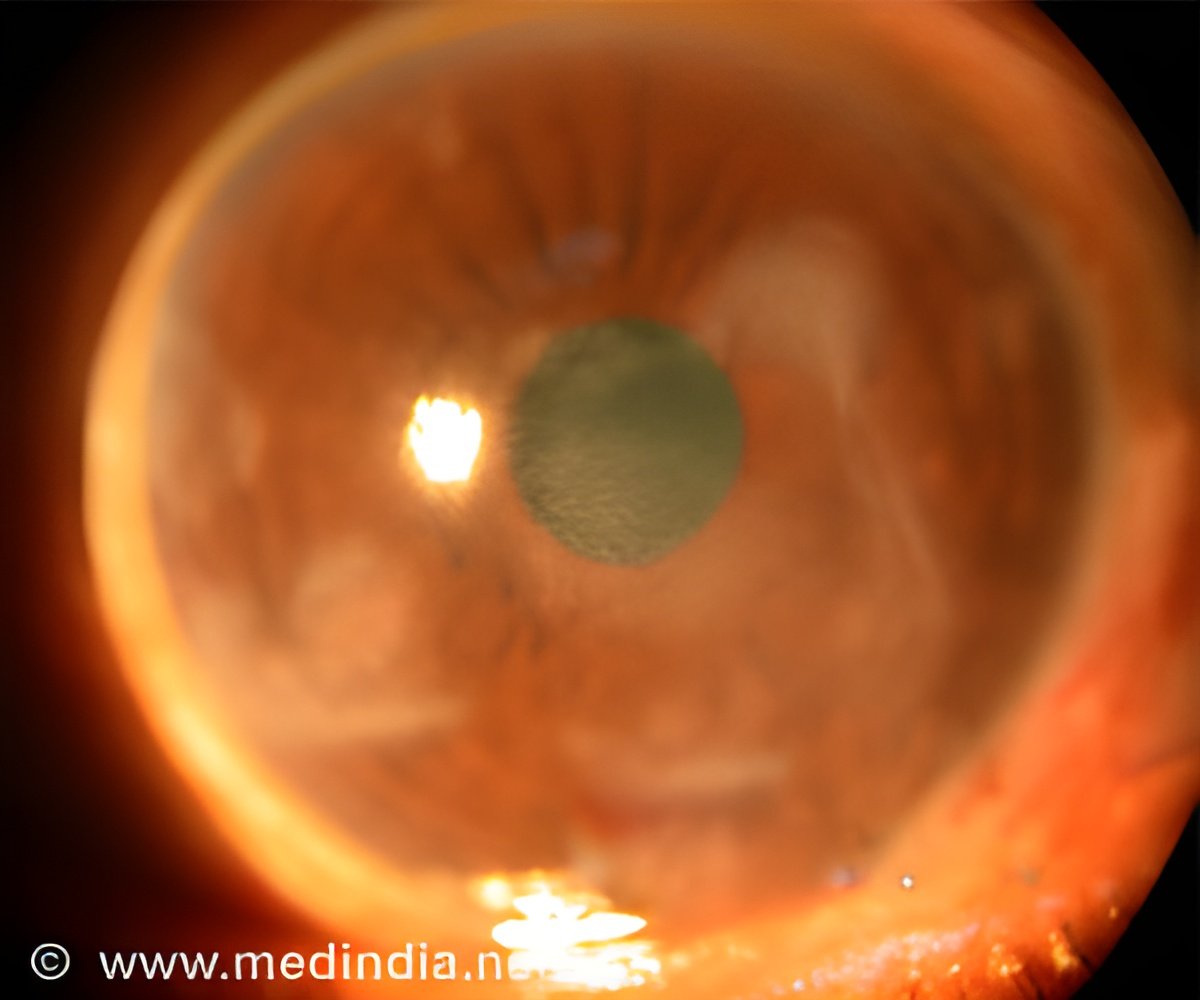

A new study published in the open-access journal PLOS Biology by Elisa Castaldi and Maria Concetta Morrone from the University of Pisa, Italy, and colleagues investigates the brain's capability to process visual information after many years of total blindness, by studying patients affected by Retinitis Pigmentosa, a hereditary illness of the retina that gradually leads to complete blindness. The perceptual and brain responses of a group of patients were assessed before and after the implantation of a prosthetic implant that senses visual signals and transmits them to the brain by stimulating axons of retinal ganglion cells. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging, the researchers found that patients learned to recognize unusual visual stimuli, such as flashes of light, and that this ability correlated with increased brain activity.

However, this change in brain activity, observed at both the thalamic and cortical level, took extensive training over a long period of time to become established: the more the patient practiced, the more their brain responded to visual stimuli, and the better they perceived the visual stimuli using the implant. In other words, the brain needs to learn to see again.

The results are important as they show that after the implantation of a prosthetic device the brain undergoes plastic changes to re-learn how to make use of the new artificial and probably aberrant visual signals. They demonstrate a residual plasticity of the sensory circuitry of the adult brain after many years of deprivation, which can be exploited in the development of new prosthetic implants.

Source-Eurekalert