Father Sunny Joseph has no doubts about what is required to help treat children and adults with HIV. "We need more money," he said. "We need much more, for medication especially."

The reed-thin Roman Catholic priest is administrator at Snehadaan, a community care centre located beyond the glass-fronted IT offices on the rural fringes of the southern Indian city of Bangalore.Men and women come here for treatment they cannot get elsewhere, either through poverty, lack of medical facilities, or because their families are sick, dead, unable or too ashamed to care for them.

The iron-framed beds in the centre's scrubbed, whitewashed wards also provide a place to die with dignity.

Local facilities like Snehadaan are at the heart of India's latest five-year plan to cut infection rates, yet Joseph said budgets are tight and demand is high.

The centre receives a total of 1,350 dollars per month from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and the local Karnataka Health Promotion Trust.

The Samartha Project, a five-year, 20-million-dollar US Agency for International Development (USAID) programme focusing on 12 high prevalence rural areas in Karnataka state, provides 1,200 dollars per month.

Advertisement

Out of that monthly total, 1,800 to 2,000 dollars goes on drugs. The rest goes on wages and running costs.

Advertisement

Dr Nalini Mehta, national programme officer for the UNAIDS body, said India's HIV-AIDS strategy was wide-ranging and well-regarded, with a massively increased budget in recent years.

But Snehadaan's experience indicated the scale of the task, he told AFP ahead of World AIDS Day on Monday.

"There will be individual centres who will say there is not enough (money). There is scope for a lot more and I don't think that the government doesn't know that. They do understand but they are upscaling," he said.

Despite the pressures, the 42 staff at Snehadaan work to provide everything from counselling and support to palliative care for some of the 500,000 people in Karnataka with HIV and AIDS-related illnesses.

Between 2.0 million and 3.1 million people are estimated to have HIV-AIDS in India, according to the latest government estimates, and Karnataka is one of six states where prevalence is highest.

As in other areas of health care, many of the country's poorest slip through the net.

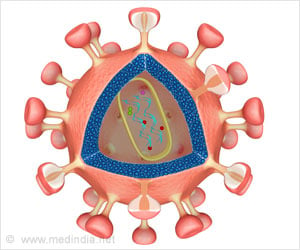

So-called "first-line" anti-retroviral therapy (ART) - a cocktail of drugs to slow the effects of the virus on the body's immune system - is free in India's patchy public health system.

For those whose bodies develop resistance to the drugs, second-line ART costs 14,000 rupees (280 dollars) for two months' treatment.

That puts it way beyond the means of people in impoverished rural areas where HIV is spreading and where the average salary is as little as a dollar day.

UNAIDS has expressed concern that second-line ART and paediatric treatment is "inaccessible" in most Indian states.

As a result, Snehadaan follows a similar strategy to schemes targeting high-risk groups such as sex workers and intravenous drug workers: prevention and myth-busting.

"We can see from our experience from 10 years ago that when someone died, no one from the family would take the body away. Now they take the body back to their native places," said the centre's medical trainer Madhu Babu.

"That shows that there has been some change."

Older people's views are more entrenched, he said, but children could spread a positive message.

At present, the centre has 50 beds, and 20 children aged 11 and younger live on site and receive treatment when they are not in class at the Shining Star School.

The colourful plastic climbing frames, smiling class photographs on the walls and a star-covered Christmas tree contrast with the ghostly figures lying motionless and dying in nearby wards.

The youngsters were either born with the disease, orphaned by it, or their families were unable or unwilling to care for them. Some mainstream schools also refused to teach them.

Teacher Christeena Nalini Radhamma says the scheme seems to be working.

"These children enjoy it here. As a form of punishment we say we will send you home, and they don't want to go," she said.

Source-AFP

LIN