Emory Vaccine Center researchers have shown that HIV relies upon a number of strategies rather than use any preferred escape route to escape immune system pressure.

The human immune system has the ability to temporarily overpower HIV in early infection.Studies conducted in the recent past have shown that most newly infected patients develop neutralizing antibodies. These are blood proteins that glob onto the virus and would allow patients to defend themselves - if they were facing only one target.

However, the problem occurs when HIV mutates, and disguises itself enough to get away from the antibodies. The virus eventually wears down the immune system into exhaustion.

The Emory team's findings attain significance as they suggest that even if any scientist succeeds in identifying a vaccine component that can stimulate neutralizing antibodies, HIV's capacity for rapid mutation could still be a confounding factor.

Dr. Cynthia Derdeyn, associate professor of pathology at Emory University School of Medicine, Emory Vaccine Center and Yerkes National Primate Research Center, says that a single type of neutralizing antibody may not be enough to contain HIV.

"These neutralizing antibodies work really well - they hit the virus fast and hard. But so far, every time we look, the virus escapes," she says.

Advertisement

They isolated individual viruses over the first two years of HIV infection, and tested how well the patients' own antibodies could neutralize them.

Advertisement

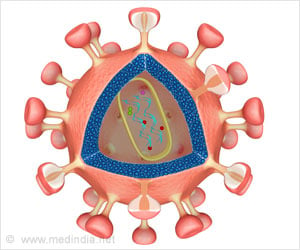

In both patients, some viruses mutated part of their outer proteins so that after the mutation, an enzyme would be likely to attach a sugar molecule to it.

Though the sugar molecule interferes with antibody attack, this tactic, known as the "glycan shield", was not observed in all cases.

Other viruses mutated the part of the outer protein that the neutralizing antibodies stick to directly. In both patients, many changes in the virus' genetic code were necessary for escape.

"We need to understand early events in the immune response if we are going to figure out what a potential vaccine should have in it. What we can show is that even in one patient, several escape strategies are going on," Derdeyn says.

According to her, that means that in order to be immune to HIV infection, someone may need to have several types of neutralizing antibodies ready to go.

Seeing how the virus mutates will allow researchers to choose the best parts to put in a vaccine, she says.

The results are online and scheduled for publication in the September issue of the journal Public Library of Science Pathogens.

Source-ANI

ARU