Jachinson Chan's daughters, aged 11 and 13, are ferried to an extracurricular activity every day of the week -- from Spanish to guitar, tennis and extra mathematics.

"People think we're crazy," he said -- but not because his children are too busy. "We're a joke among our friends because we don' have that many activities."

And not just any activity is good enough. "Piano is no longer considered a big deal," said Chan. "If your kid is in primary school and he or she can play the piano really well, the schools will yawn.

"You need trombone, for example -- something that not many people want to play. Parents are encouraging their kids to play the oboe."

OECD rankings generally place Hong Kong above the international average in education standards, and often near the top worldwide, but local universities only take 18 percent of school students.

Advertisement

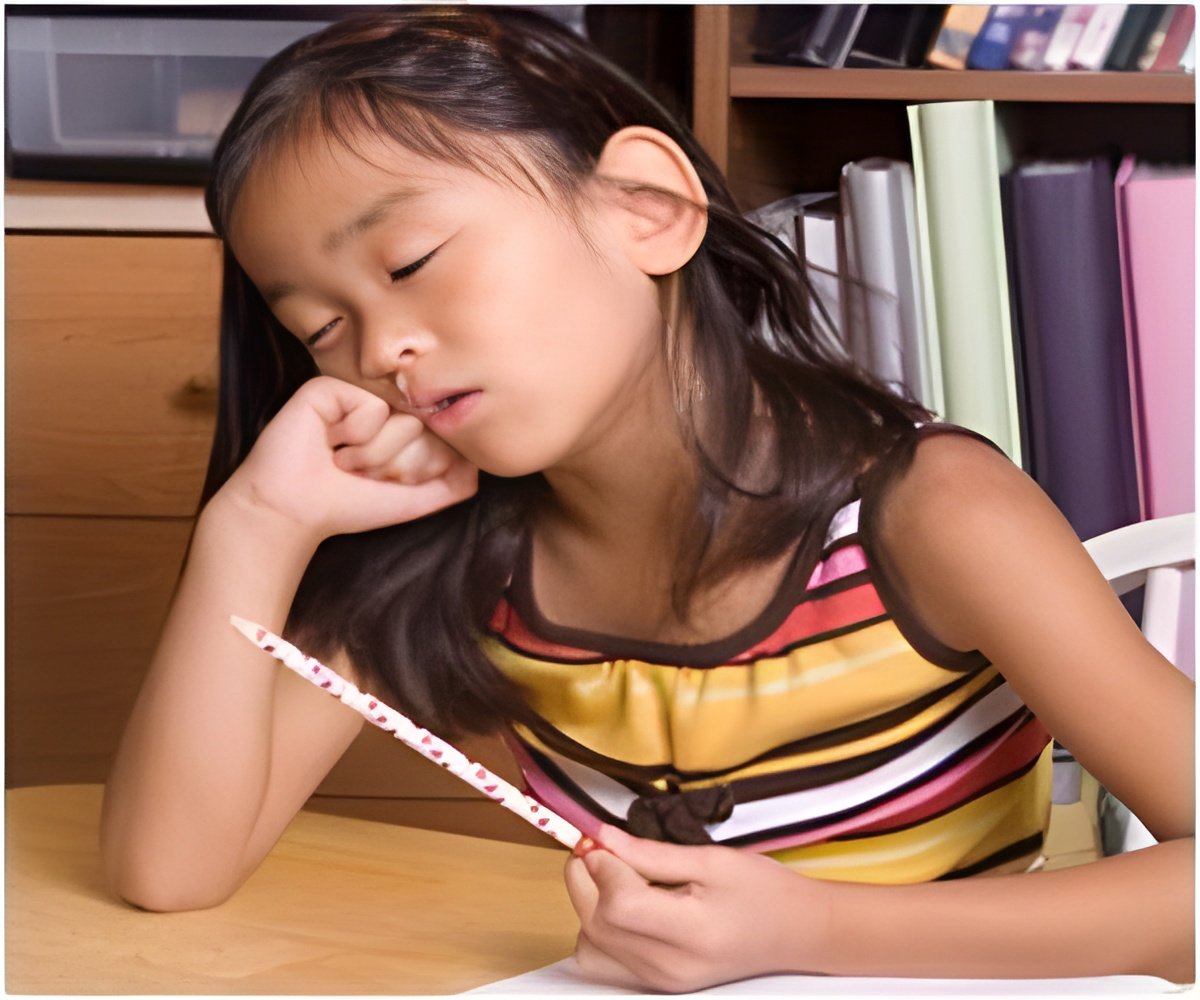

The results? A survey by retail group Plaza Hollywood in April said more than two-thirds of Hong Kong parents placed a higher premium on their child's grades than their health -- though the survey was unclear about its methods.

Advertisement

Local charity the KELY support group, which works with young people and parents across the social classes, has launched a campaign simply to encourage parents to spend more time with their children.

Executive director Chang Tung said that the charity's clients face unprecedented stresses, not confined to those in poverty.

"Parents are really struggling. They work very long hours," he said.

"The majority of parents we speak to love their children. They really want to do the best for them but it's hard for them to find that middle way."

Maria Leung said that when her son, now 14, was in primary school, "I was feeling quite pressured. They have to work really hard so as to guarantee places at secondary school.

"I know that affected him, but sometimes I can't control myself. As a parent I think, somehow, you have to walk very carefully."

But she points out that the ferociously competitive education system is only part of the story. Another is China's Confucian parenting values, which place a high value on the roles of parents and children within the community.

"Hong Kong children have a very unique style -- they may be overpowered by their 'helicopter parents'," Leung said.

She admits she sometimes hovers, helicopter-like, around her son -- but says that this, for Chinese parents, means "really taking care of the child".

Leung recalled taking her son to a playground favoured by expats when he was a young child.

"I can see that the Westerners, they like to let the child fall himself. But I am the one who chases him -- on the monkey bars, on the swing. This is a very different attitude," she said.

Professor Qian Wang of Hong Kong's Chinese University, who has studied differences between Chinese and Western parenting styles, says that "what's special about Chinese culture in terms of parenting is parents assume a lot of responsibility to make sure their children succeed in the future.

"In the west it is -- let a child be free, have autonomy and feel good about him or herself no matter what.

"In Chinese culture we think parental love is to really care for the child and make sure the child will succeed in the future in society... (but) in Western culture that could be viewed as intrusive."

As different cultural influences come into play, for many parents it is a case of adjusting their expectations.

Leung said that when her son began secondary school, she was surprised to hear the headteacher ask parents to "let go -- to sit back a bit and let them do it".

"I remember that well," she said. "We have tried to support (our son) from behind, when he needs it, to help him have confidence. I want to keep a bit of distance with him because I want him to be independent."

She recalled that at the end of "Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother", Chua adapted and relaxed her approach to parenting.

"She learnt a lesson. I hope tiger mothers here can learn the same lesson as Amy," Leung said.

For Chan, after fighting to secure his daughters' entrance to a top primary school, he and his wife decided to move one of them out again to a less intensive environment.

She suffers from dyslexia, and the burden of intensive and multilingual learning was a strain not just on her but on her mother.

"It's like buyer's remorse -- you actually get the product, you get in, and you're like 'gosh it's really difficult'," he said. "My daughters were telling me that a lot of their classmates leave."

Still, Chan -- who spent many years in the United States and now runs his own language school -- remains a fan of the Hong Kong school of parenting.

"We're much more goal-oriented: everything we do as a parent has a purpose," he said.

"In the States, you dream big -- everybody wants to be an NBA star, an actress. There are these great success stories that become these myths, but nobody talks about the failures."

In Hong Kong, he said, "We dream practically. We have a practical side to the dream."

Source-AFP