A study published on Monday has found that eggs from cows, rabbits and other animals are not a good source for creating embryonic stem cells, the master material that could one day repair tissue damage, replace organs, and reverse degenerative diseases.

But, in the same study, US researchers made a significant advance in the cloning of human embryos, which could be a path to producing a host of patient-specific treatments."This study shows for the very first time that cloning really works and that DNA is reprogrammed," said co-author Robert Lanza, the chief scientific officer at Advanced Cell Technology.

Lanza and his team were able to replace the nucleus of a number of embryos and bring the clones to the morula stage, where they had divided into eight to 16 cells.

In the human embryos, they were able to prove that the DNA was reprogrammed because the same genes were activated as in a normal embryo.

But something went wrong when the nuclei of rabbit, mice and cow embryos were replaced with a human nucleus.

"We would get these beautiful little embryos but it wouldn't work: instead of turning on the right genes the animal eggs would turn them off," Lanza told AFP.

Advertisement

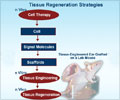

The dream is to coax these cells into becoming lab-dish replacements for heart, liver, skin, eye, brain, nerve and other cells destroyed by disease, accidents, war or normal wear-and-tear.

Advertisement

The most promising method is to reprogram skin cells so they behave like embryonic stem cells. But these "induced pluripotent stem cells" (iPS) are currently created using harmful viruses and are not safe for clinical use.

Cloning embryos so that they have the same DNA or tissue type as the patient could be safe for clinical use.

But researchers have not yet derived an embryonic stem cell line from a cloned embryo or found an efficient way to clone human embryos.

There had been hope that the animal eggs could be used as a substitute for human embryos, which are difficult to harvest and controversial to use.

"This very important paper suggests that livestock oocytes (the cells from which eggs develop) are extremely unlikely to be suitable as recipients for use in human nuclear transfer," said Ian Wilmut, director of the Centre for Regenerative Medicine in Edinburgh and editor-in-chief of Cloning and Stem Cells, which published the paper.

"This is very disappointing because it would mean that production of patient-specific stem cells by this means would be impracticable."

Working with human embryos is also impractical because the high failure rate means it takes hundreds of eggs to create a single stem cell line, said Alan Trounson, president of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine.

"Most people are working on IPS cells (stem cells derived from skin) rather than nuclear transfer because it's so difficult to get human eggs," Trounson said.

"Their work is endorsing that we could use human eggs but I don't think it helps us, to be honest, in actually being able to do it because it doesn't show that it could be improved dramatically."

Trounson said human cloning can still be important in addressing some serious genetic diseases because it would allow for the manipulation of mitochondria, which run cell function and contain DNA.

But Lanza said it's too soon to give up on embryonic stem cell research.

"We need to continue research on both fronts because we don't know if IPS cells or cloning will be better," he said.

"It's good to have a backup approach."

Source-AFP

PRI/SK