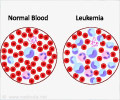

Interest in cellular reprogramming surged after researchers in 2007 announced they could wind back the DNA of adult, or mature, cells.

Restored to their immature state, the cells become highly versatile stem cells which -- so it is hoped -- could then be coaxed into developing into tissue-specific cells, such as heart, brain or muscle cells.

The big advantage of these "induced pluripotent stem cells," or iPSCs, is that they would be free of the moral controversy that has dogged use of embryonic stem cells, or ESCs.

Many scientists have also assumed that, because iPSCs are derived from one's own DNA, they will be accepted by the immune defences as friends and thus be spared from attack.

Not so, according to the new research.

Advertisement

His four-person team tested iPSCs and ESCs on mice that had been genetically modified to have identical DNA.

Advertisement

The surprise, though, was that they went into attack mode when they met the iPSCs.

The responders were T cells -- the heavy artillery of the immune system, which are designed to destroy invading microbes. They are notably the problem that has to be curbed when someone receives an organ transplant: without drug controls, the defenders destroy the implanted tissue.

In a phone conference with journalists, Xu said the findings were a clear setback for iPSCs, but exactly how big a problem was for now unclear.

The T-cell attack only occurred with certain kinds of iPSC-derived cells, not all, and more work was needed to find out which ones and why, he said.

"If it's only limited to certain cell types, then maybe other cell types can still be used for transplantation without the worry of being rejected," he said.

"If it's a very widespread problem, that becomes another issue. So at this moment, it's very difficult to say how big the hurdle is."

For now, ESCs remain "the gold standard" of versatile stem cells and should not be abandoned, in spite of the controversy surrounding them, in favour of iPSCs, he said.

Xu said he suspected that the problem with iPSCs lay in errors that occur in the DNA code when the cells are reprogrammed.

In February, a team led by Joseph Ecker of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California, found that the transformation from adult cell to stem cell was incomplete.

DNA errors pop up in an area of the genome called the epigenome, which essentially is the switching system that turns genes on or off and determines their level of activity, they reported.

Source-AFP