Scientist believe that human’s distant ancestors won the battle against the now extinct virus 4 million years ago but it left the human species vulnerable to HIV today. AIDs one of the most dangerous diseases of the present century and one of the most researched one still leaves many questions unanswered about its origin.

Many researchers believe that the answers to the origin could be found in the jungles of central Africa. The understanding to the origin might lead to finding an effective treatment for AIDS.Studying the antibodies in chimpanzee faeces have suggested that the virus jumped into humans from a Cameroonian population of chimps early in the last century. A separate group of chimps in Cameroon has infected a handful of locals with a nonpandemic version of HIV. Waste from wild gorillas suggests they are probably responsible for a third form of the virus.

Michael Emerman of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Centre, in Seattle, describes how he and his colleagues looked at a different virus ( PtERV1) which was active about a million years after human lineage parted from the chimp one. It appears that ancient hominids successfully evolved immunity to that virus, but in doing so were somehow left defenseless against HIV.

The ancient virus, PtERV1, left relics of itself in the DNA of modern chimpanzees.

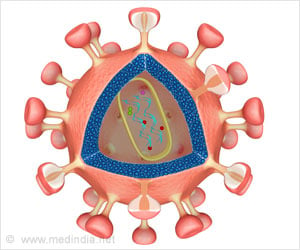

All primates make “TRIM5alpha”, which protects them from viruses in the same broad category as HIV. But each species makes a slightly altered version, making them immune to different combinations of such viruses. The type that rhesus macaques produce, for example, confers complete resistance to HIV; the sort made by baboons slows that virus’s replication by 50-fold.

In fact, when geneticists first compared the genomes of humans against those of chimps, the biggest difference is the presence [in nonhuman primates] of this virus, PtERV1.There are about 130 copies in the genomes of chimps and gorillas, and maybe other primates, but it's not present at all in the genome of humans.

In the case of Humans, the gene's ability to block infection against PtERV1 does not seem to extend to another dangerous retrovirus, HIV.

Advertisement

Retroviruses can insert themselves into their hosts' DNA, sometimes leaving behind their genes as evidence of the infection. Experts estimate that 8% of human DNA is made up of defunct viral genes. The researchers were able to partly reconstruct the virus, though it has been extinct for 3 million to 4 million years. They found that the human version of the TRIM5-alpha protein could bind to the virus, labeling it for the cell to destroy.

Advertisement

This antiviral protein appears to be able to fight one virus or the other.

Early humans evolved a defense against PtERV1, but left themselves wide open to the HIV pandemic 4m years later.

Source-Medindia

BIN/M