A radical surgery involving the removal of that part of the brain responsible for epileptic seizures has proved successful in the case of a 14-year-old English boy.

Epilepsy is a chronic neurological disorder characterised by repeated seizures.The brain is comprised of more than 100 billion nerve cells, called neurons, which control the body's functions, senses and thoughts.

These neurons communicate with each other using very small electrical signals.

A seizure happens when there is an "electrical storm" or temporary disruption to the way the neurons send and receive signals.

One person in 50 will have epilepsy at some point in their life, and about 450,000 people in the UK have the condition.

The illness has a wide range of causes, including head injuries and even alcoholism.

Advertisement

In April 2001, just as Sean was nearing the end of this harrowing treatment, he suffered a bleed at the back of his brain.

Advertisement

As the seizures increased in frequency, going up to 20 a day, Sean was diagnosed with epilepsy.

"It seemed so desperately unfair. He'd survived cancer and all the horrible treatment that entails," said his mother Jane.

"But just when it looked like he could start afresh, he developed this dreadful condition. I felt so helpless."

Then Sean's doctors told the family about a radical surgery being offered by Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) in London, an NHS hospital.

The surgery is carried out on about three per cent of epileptics and these tend to be sufferers who fail to respond to medication and whose seizures are triggered by one damaged area of the brain. The success rate is around 70 per cent.

After the family agreed to initial tests, an MRI scan revealed an immediate complication.

'Sean's case was unusual because there were two separate parts of the brain which could be responsible for the seizures,' explains Professor Helen Cross, head of paediatric neurology at GOSH.

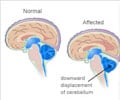

The first was located on the surface of the temporal lobe at the left hand side of the brain, an area likely to have been damaged by the brain bleed.

The second was in the hippocampus, deep in the brain, which is responsible for memory.

This was likely to have been caused by the fits themselves, which meant Sean's memory would deteriorate over time if the seizures continued.

Tests confirmed both of the damaged areas were active during fits. For there to be a chance of curing Sean's epilepsy, both would have to be removed.

The operation was far from risk free. The damaged tissue on the temporal lobe was close to the part of the brain responsible for language. Doctors feared surgery to cure Sean's epilepsy could harm his ability to speak.

The hippocampus - the other source of damage - lies at the top of the spinal cord and any complications could cause paralysis.

It was terribly risky. His parents left it to him and the boy decided to have a go at it. That was his only chance any way. And now he has won that desperate gamble.

The five-hour operation, on June 15, 2007, was carried out by paediatric neurosurgeon William Harkness. He made an incision into the scalp, before lifting up the skin and removing a small piece of bone to reach deep into the brain. Using micro-instruments, he cut away the damaged tissue which was sucked out through a fine tube.

After the operation Jane and Paul Goldthorpe faced an agonising wait to see if their son had been affected by the surgery.

'It felt like a lifetime,' says Jane.

'Eventually he opened his eyes, and just as a nurse prepared to give him an injection he muttered quite clearly: "What's that for?" I knew then his speech was intact. The relief was overwhelming.'

Their fear of paralysis was also alleviated when it became clear Sean could move his legs.

Despite undergoing such radical sugery, Sean spent just four days in hospital and a further six weeks recovering at home and regaining his strength.

But only an absence of seizures will prove the operation has worked. 'There is no time limit to determine whether he is cured,' says Professor Cross. 'But for every year that passes he is less likely to have further seizures.' Three months after the surgery, Sean remains seizure-free.

'He still has to take it easy because his body has to recover from such massive surgery. So he can't do vigorous exercise or head a football — much as he would like to,' says his mother.

'But otherwise he can just enjoy himself as any other teenage boy would. Just going for a ride on his bike makes him feel so good.

'Now he has started his final year at school and it's wonderful for him to sit through a lesson without having a fit. As a family we feel like we've had a new lease of life.

'I always worried about Sean's prospects. Now he has a real chance of having the future he deserves.'

Source-Medindia

GPL/C