Much of President George W. Bush's legacy may come under withering fire but in one area at least, it will be viewed positively: his contribution to fighting AIDS.

By yanking open the financial spigot, say experts, Bush reversed years of retreat in the war against acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and ended de-facto apartheid between rich and poor in access to life-saving drugs.During his two terms, the United States pumped nearly 19 billion dollars into fighting AIDS in poor countries, saving many people who had been denied therapy that only rich economies could afford.

In 2002, Bush helped launch the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, to which the United States is the biggest single contributor, and in 2003 he set up the President's Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), focussing on 15 countries, mainly in Africa.

PEPFAR has become the springboard for an even more ambitious 39-billion-dollar programme running from 2009 to 2013.

"Under the Bush administration, there has been an extraordinary increase in resources dedicated to the fight against AIDS in less developed countries," Michel Kazatchkine, executive director of the Global Fund, told AFP.

PEPFAR "has literally saved millions of lives," said Peter Piot, who stepped down at the end of last year after 13 years as head of the UN agency UNAIDS.

Advertisement

Advertisement

"We hope they will continue to deliver real results in the years to come. These investments offer health and opportunity to millions of people around the world."

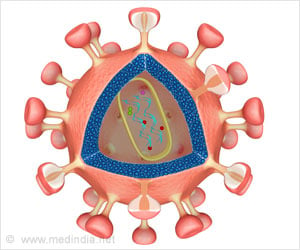

In 2002, around six million people around the world needed the famous "cocktail" of anti-HIV pills to save their lives. Only around 300,000 of them had access to it, most of them in Brazil.

The others could not afford a drug regimen costing thousands of dollars a year and - according to Big Pharma - was too complex to dispense in poor countries.

The situation was especially desperate in sub-Saharan Africa, where just 50,000 out of an estimated four million needy people had access to the lifelong therapy.

Today, the global tally has risen to about 3.5 million people.

"It's a tremendous accomplishment, and one of which the Bush administration should be extremely proud," said Seth Berkley, head of the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI), stressing though that an even longer road lay ahead.

Overall funding for AIDS rose from 1.4 billion dollars in 2001 to 10 billion in 2007, but needs to be at least 15 billion in 2010, according to UNAIDS.

On World AIDS Day last December 1, Barack Obama himself saluted Bush, singling out his "leadership" on AIDS, especially in Africa.

Bush did not, of course, achieve all this alone, nor was his programme without hiccups, say specialists.

Credit should also go, for instance, to the Clinton Foundation, for twisting the arm of pharmaceutical companies to lower their prices; to manufacturers of generic drugs for providing competition; and to the Gates Foundation and other major donors.

Critics attacked Bush for requiring PEPFAR to earmark funds for promoting sexual abstinence before marriage, an initiative they blasted as dangerously unworkable among sexually active teens.

Twenty percent of PEPFAR funds had to be spent on preventing HIV, with at least a third of allocated to abstinence counselling. But the 2009-2013 programme scrapped such detailed requirements.

Grassroots workers say the row should not obscure the huge boost in many lives that began under Bush, nor the dazzling proof that HIV drugs could be administered easily in impoverished settings.

"When I first started going to Uganda in the early Nineties, you would leave the airport in Entebbe and drive to Kampala, the capital, and on the side of the street, there were coffin makers," Andrew Fullem, a veteran in AIDS work with John Snow Inc., a US consultancy on public health.

"Everybody who had previously been cabinet makers and had done things with woodwork had become coffin makers, just because it had become an industry, a business in Uganda.

"It's not the case today. There's not that pervasive sense of death any more."

Source-AFP

PRI/S